See Reverse Side for Title: Part I

A consideration of the Lovin' Spoonful, the Blues Project, Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and Barry & the Remains

By Louis Black, Fri., Oct. 15, 2010

Okay, no one was better than Eric Clapton, but was Jeff Beck, this new guitarist playing for the Yardbirds, anywhere near as good as the Blues Project's Danny Kalb? The question may now seem ludicrous, but not in the mid-1960s, when it was a burning question among the music fans I knew.* Where we grew up, what we listened to and when we listened to it, what music there was and what music was to come were all factors that helped shape and still affect our taste in music. We are what we eat, and the times, they have changed.

This is a near completely free-form essay held together by the most meager of conceits: the most important and influential bands from when I was a teenager growing up and going to high school in Teaneck, N.J. This, then, is about the music, albums, and history of the Blues Project, Lovin' Spoonful, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band, and Barry & the Remains, all circa 1965-1967. Almost all the groups continued producing albums after '67, but those albums are more interesting for their pedigree than content.

Although admittedly arbitrary in which bands and albums are focused on, the selection is really not completely random. These were among the most well-known and influential bands of the time, but time has seen their reputations fade. It's not that they're now completely forgotten but that the current low regard for these acts doesn't begin to indicate what their standing once was. What's really lost is the extent of their impact. Any number of people could write something along these lines, but a difference in where they grew up or a year or two in age would strongly affect which groups they'd include.

The mid- to late 1960s were a time when an enormous amount of music was being made and released, but there were still only a handful of ways to listen to it all. Even though there were regional hits and regional stars, outside of infrequent tours, the only ways to hear new music were through a handful of FM radio stations or on a record player. Albums were listened to over and over while cover art was studied like the Rosetta stone.

There are many scholarly essays to be written on the roots, gestation, distillation, distribution, and consumption of American music beginning in the last half of the previous century (see "Naked If I Want To," Jan. 8). This isn't one of those but rather a bargain-priced shopping mall approach. One can isolate so many different musical styles that influenced early rock bands, but too often this is an exercise in reductive descriptions. Bands considered as folk-rock or blues-rock were rarely that narrowly and specifically influenced. In the true American melting pot way, all kinds of styles were thrown together in the Mixmaster of music-making. This resulted in not purebreds but rather mixed breeds with exact ancestral heritages not entirely clear.

It was the farewell performance by an Austin band that had gone from unknown to widely loved (at least locally) in a surprisingly short period of time. Three years later, never able to graduate from their popular but Austin-centric status, they were calling it quits. A writer for the Chronicle, much younger than myself, was exploding with enthusiasm when he came over to talk to me. This was the first band that had musicians he knew in it. He'd watched them grow and thus loved them with the unique intensity of first love. I liked them well enough but with a much more streamlined passion.

Not as an absolute invariable rule but as a reasonable and consistent indicator, individuals' tastes often lean toward what they experienced during their formative years. Preferred taste in pizza, for example, can be traced usually to the kind of pizza one grew up eating. Whether it's New York, Chicago, Boston, Midwest, or whatever, the most familiar pizza is often described as the best. Popular cultural preferences are similarly determined. Often taste has been affected by three factors: what was nationally popular and relevant, what was regionally or locally important, and personal development.

Many of my rock-writing brethren, for instance, have a deep passion for Kiss, especially those a decade younger than me. When Kiss first became prominent among my peers, the band was regarded as a joke. It's not uncommon for younger writers to have never even heard of bands I regard as being of major importance.

The national homogenization of Top 40 radio was well along when I first started taking rock & roll seriously, but there were still regional scenes with major acts not known outside a geographical area. It wasn't uncommon for any number of these acts to chart on regional radio. Within a decade, outside of certain FM stations, music was mass-programmed.

Raised near New York City in New Jersey, I was very taken by the Rich Kids' "Plastic Flowers." At the same time, Barry & the Remains were among the most prominent New England rock bands, even serving as an opening act for the Beatles.

Growing up, our favorite live bands were local rockers, none of which ever achieved much recognition. It wasn't at all like Austin. The really influential acts were distant, even those that regularly played in New York. When I moved to Boston in 1968, the favorite local band was J. Geils, which had yet to score a breakout hit.

All of this has to do with a fascination about how we listened to and discovered music growing up compared to how that happens now. Then it was the vinyl age, when records were played on turntables. Eight-track tape players were mostly in cars, though later there were cassette tapes. Listening to vinyl, one had a choice. Every 20 to 30 minutes or so, you could get up and flip the record over or take the album off to put another one on. Most lower-end and midgrade turntables made it possible to stack a number of albums so that when one finished another would drop. The downside was that if a vinyl-ista friend visited, they'd go into shock over the brutal wear and tear on the albums.

Or you could listen to the same side over and over. I've always had music on when writing and would often listen to one side of an album for hours. Now we live in a Digital Age in which all kinds of music are readily and constantly available.

Before computers, cable TV, and handheld technologies, adolescence moved at a glacial pace, so although music was often released at a machine-gun rate, it appeared to be happening in slow motion. In the greater New York City area in the mid- to late 1960s, the bands that were the highest regarded and the most influential were the Blues Project and the Lovin' Spoonful (NYC), the Paul Butterfield Blues Band (Chicago), and Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band and Barry & the Remains (New England).

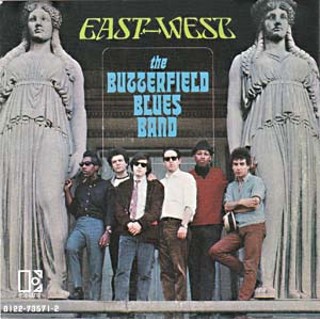

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band's music was raw, rocking, powerhouse Chicago blues. Butterfield was in blues clubs beginning way before he was old enough to legally enter them. Butterfield and his running buddy Elvin Bishop regularly got to hear such blues greats as Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Little Walter, and Otis Rush. When they were asked to be the house band at north side club Big John's, they hired bassist Jerome Arnold and drummer Sam Lay from Howlin' Wolf's band.

Guitarist Michael Bloomfield, who had also begun hanging out at blues clubs before he was of age, soon joined the band. The addition of Mark Naftalin on keyboards completed the lineup that recorded the first album released, 1965's The Paul Butterfield Blues Band on Elektra. When Lay became too sick to perform, jazz and blues drummer Billy Davenport was recruited. He proved an ideal contributor to 1966's East-West, the band's second LP. Bloomfield, Davenport, and Arnold left after that album was released, with Bishop moving up to lead guitar.

With electric instruments and a darker urban sensibility, the band brought Chicago blues, which evolved from Delta blues and other influences, to the nation. Over 10 years, beginning in the mid-1960s and stretching through half of the next decade, there were ongoing debates about race and music, whites and blacks, the blues and rock. The focus of these centered on exploitation, cultural imperialism, base racism, and American culture. Making music heavily rooted in pure Chicago blues, the Butterfield band broke nationally long before any of the black artists and groups that pioneered the music. Even those not militantly committed to the more extreme positions regarding these discussions acknowledged it was a shame that black blues musicians had to wait for rock bands to kick the door open.

Now that seems too simplistic in a number of ways. Not only was racism as institutionalized in the music and entertainment businesses as it was everywhere else in the country, but this country has often privileged the hybrid over the pure, which by default is the underlying theme to the story of American rock.

1963: Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band

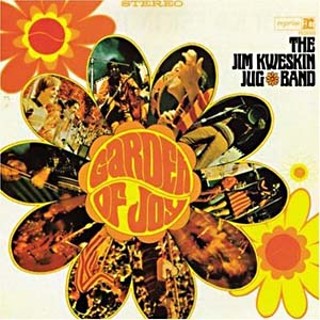

A fascinating story of profound contradictions, Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band not only embraced and perfected playing in any number of American music styles, they did it with joy. Traveling around the States in the early 1960s, Kweskin thought up the idea of the band and put together its first incarnation when he got back to Boston. This was around 1963, when the Boston folk scene revolved around Club 47.

There had been popular American jug bands in the 1930s, but Kweskin was not interested in being faithful and made it clear that he didn't consider his band revivalist. "We not only have no one 'tradition' to try to be faithful to," he told writer Nat Hentoff, "but for much of what we play, we don't know if we even have tradition to be concerned with. We can do almost anything we want."

The band mined many veins of Americana, playing all kinds of instruments to get to where they wanted to go, including kazoos, steel guitars, combs, spoons, and washboards. Combining so many influences into a fluid sound proved influential to a number of other musicians and groups.

The heart of Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band always was Kweskin and the remarkable Geoff Muldaur (who later joined one of Butterfield's bands). The original band included guitarist Muldaur, banjo player Bob Siggins, Bruno Wolf on harmonica, and Fritz Richmond on jug. As with many jug bands, the personnel changed frequently. Mel Lyman replaced Siggins on banjo only to move over to harp when Bill Keith took on the banjo duties. Singer Maria D'Amator, who joined the band, would soon marry Muldaur.

The band frequently toured, played festivals, and guested on TV, while also releasing great albums prolifically. Traditional music experienced its heyday in the mid-1960s, but by the end of the decade, it had been supplanted by rock.

But the Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band story isn't just about music. It's a much longer tale. Mel Lyman emerged as a spiritual leader not just of the band itself, but of a larger community. In 1966, he published Autobiography of a World Saviour. Lyman, Kweskin and his family, maybe some other Jug Band members, and a number of other people joined together as a commune known as the Mel Lyman Family. They settled into the Fort Hill area of Roxbury in Boston, with Lyman as avatar and spiritual leader. Any number of musicians and writers of the time were either in or interested in the family.

During 1967 and 1968 they published Avatar, a biweekly underground newspaper promoting Lyman's teachings. As with any such group there was a certain amount of controversy surrounding the family, which was covered in Boston's straight and underground press. There was also some national coverage, including "God Is Back, He Says So Himself," a piece in Esquire by L.M. Kit Carson with a photograph by Diane Arbus. David Felton published a two-part article, "The Lyman Family's Holy Siege of America," in Rolling Stone, which was later included in the book Mindfuckers: A Source Book on the Rise of Acid Fascism in America. Collecting material on Charles Manson, Mel Lyman, Victor Baranco, and their followers, Felton, Robin Green, and David Dalton published Mindfuckers on Rolling Stone's Straight Arrow Books.

The family denied all the charges.

Concentrating on the commune and the construction business, the Lyman Family slipped out of the spotlight for a while until commune member Mark Frechette, who starred in Michelangelo Antonioni's Zabriskie Point, was involved in a bank robbery. He was captured, tried, and sent to prison, where he was murdered. As far as I know, the commune is still alive and well, having grown somewhat rich over the years.

That's really a footnote to the story of the Jug Band, music-loving minstrels who brought together so many influences, entertained vast audiences, and helped change American music. A partial discography:

1965: Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band, Jug Band Music (Vanguard)

1966: Jim Kweskin with Mel Lyman & Fritz Richmond, Relax Your Mind (Vanguard)

1967: Jim Kweskin & the Jug Band, See Reverse Side for Title (Vanguard)

1967: Jim Kweskin, Jump for Joy (Vanguard)

1967: The Jim Kweskin Jug Band, Garden of Joy (Reprise)

Part II

Will appear soon, covering the Blues Project, the Lovin' Spoonful, Barry & the Remains, and the Elektra Records compilation What's Shakin'. As with so many things I write, I am deeply and eternally indebted to the extraordinary scholarship and writing of Richie Unterberger.

Jim Kweskin and Geoff Muldaur, 2010 Austin Music Awards showcasers, return to town on Saturday, Oct. 16, for the Austin Friends of Traditional Music's fifth annual Austin String Band Festival, Oct. 15-17, at Camp Ben McCulloch in Driftwood.