Bygone Buildings

There Are Ghost Towns Hidden Right Here in Boomtown

By Devin Greaney, Fri., Jan. 26, 2001

In go-go Austin, displacement is the rule. A video store seems to open in the time it takes to rewind a tape. A vacant lot becomes a Dell facility seemingly overnight. Subdivisions appear where corn or cows were a month before.

Sure, we have our fair share of landmarks. But what gets saved -- and how it gets saved -- is relatively random, having more to do with the sentiments and/or PR needs of private landowners than with any kind of coherent preservation policy. A significant structure can go unmaintained and unrecognized for years, only to be transformed almost instantaneously into a parody of itself when the good times roll. There is virtually no legal protection for historic structures on privately owned land and, likewise, little public money for restoring and maintaining them, so that at times it seems like privatized Disneyfication is the best we can hope for in the way of historic preservation.

And then there's benign neglect -- in some ways, a more attractive option. Certainly a more romantic one. And, in non-boom times, the option of choice. Indeed, for every Driskill Hotel, Capitol building, or Governor's Mansion, there's a more mysterious, usually creepier, old building or site with an equally compelling story to tell. Places put here for a reason but not necessarily for posterity, often passed by but seldom visited, neglected but not destroyed. Ghost towns hidden in the boomtown.

-- Devin Greaney

The Cabin

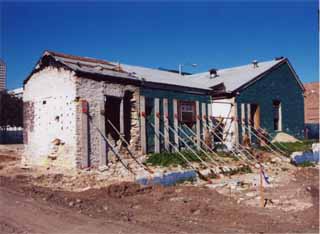

Those in need of an easy metaphor for the course of downtown development might want to consider this one: In 1836, Susanna Dickinson, one of the few survivors of the battle of the Alamo, was dispatched by Santa Anna to deliver the news to Sam Houston that San Antonio had fallen. Her place in history as the "messenger of the Alamo" secured, she embarked on a series of marriages, eventually settling down with Joseph William Hannig of Lockhart, moving to Austin, and in 1896 or so setting up house in a stone cabin near what is now the corner of Fifth and Neches.

Dickinson is a well-known historical figure in Texas (she'll be the only woman represented on the façade of the Texas State History Museum), but her former residence chugged along in obscurity for most of its existence. Taking on the occasional addition and modification, it served as a private residence until around 1925, was used for auto parts storage for several decades, and eventually became a series of restaurants, culminating in its long stint as the Pit Barbecue. Despite the fact that it is the oldest known residence in downtown Austin, it was neither lovingly preserved nor even often recognized, but simply put to use, for most of the 20th century.

But that's because there wasn't much money to be made from its removal. And as we all know, that was then: The entire block around the decaying, barbecue-smoke-damaged Dickinson cabin has now been razed for the construction of the Convention Center hotel. In a bit of a quandary about the historic nature of the structure impeding progress, the city and its private development partner will almost certainly dismantle the building, and will most likely rebuild it either in a different location downtown or (and here cue laugh track) as a wine and cheese bar or gift shop in the lobby of the new hotel. -- Cindy Widner

The Park

Along a tree-lined stretch of Jefferson Street, off of West 35th and Bull Creek Road in Central Austin, a park runs along Shoal Creek. The nameless park is a regular stop for pet owners in the area, but as Austin parks go, it's not a major destination. Trees, shrubs, cacti, and an occasional piece of brick and concrete poke out of the soil.

The area looked quite different 20 years ago. Homes lined the area in this prime Central Austin neighborhood. Residents had an older, stable community with lush, green streets and lived within walking distance of businesses, schools, and churches. This was a smart growth area even before the term was in vogue.

But everything changed on May 24, 1981. In what is remembered as "The Memorial Day Floods," 3.88 inches of rain (according to official figures at Mueller Airport) from a series of mega thunderstorms over northwest Austin deluged the city, with certain areas reporting more than a foot of rain in less than two hours, changing normally dry creeks into rivers. By the next morning, 13 Austinites were dead, and $35 million in property was damaged.

Almost everyone along Shoal Creek was affected by the storm. Some of the worst damage occurred on the land along Jefferson where homes were destroyed, the bank was reshaped, and two residents were killed.

Soon after, the city bought the land and the homes were either moved or razed.

This past summer, seeing water in Shoal Creek was such a rarity someone new to the area might wonder why it had "creek" in its name. But anyone who remembers Memorial Day, 1981, knows its potential. The park is a reminder.

The Walls

Rows of stone walls are all that remain of one piece of old-time Austin.

For this location, the term "old-time Austin" needs clarifying. Many think of old-time Austin as the days of yore when rent for a two-bedroom house was less than $500 a month. Others think of the Armadillo World Headquarters and the Vulcan Gas Company. Still others can remember U.S. 183 as a two-lane country road.

But before any of those memories became memories, before there was an Austin, in fact, 63 years before Stephen Fuller Austin was born, Spanish missionaries began relocating missions in the area -- three, to be specific -- from East Texas. While on their journey, they discovered what is now Barton Creek.

Between the current Camp Craft Road access and MoPac expressway, lies a network of stone walls. These walls may have been used to corral goats and other small livestock or perhaps were used as a way to mark where permanent structures would be built. The same year, 1730, due to confrontations with tribes of indigenous people, the Spaniards relocated to San Antonio.

However, historians, as historians often do, disagree. Some believe that the Cox family, who owned the property from 1873 to 1887, built the walls.

What is not in dispute is that on the 78-plus-acre site, a group of walls were constructed with stacked rock in the thick juniper and oak forest not far from the creek. Arrowheads, along with artifacts from the 19th and 20th centuries, have been found in the area.

Texas Stonehenge? Maybe that goes a little too far, but going off the path a bit can reward local hikers with an enriching experience of area history. In 1976, the Barton Creek Corrals were listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The House

"I remember a lot of good things about the old house," said Alvino "Jimmy" Jiminez about 2307 Foster, his home from 1970 to 1989. When Jiminez left, he was the last resident of the home.

The address may not sound familiar, but many have seen the structure. The blue-and-white two-story house is on top of the hill next to the Deep Eddy Pool parking lot. Jiminez lived there with his wife, six sons, and dog Midnight. He maintained the pool and Eilers Park next to it and took care of the animals at the former Natural Sciences Center. The house was owned by the city for use by the groundskeeper. From 1965 until the Jiminezes moved in, Bessie Witcher's late husband had the job.

"I was in the side yard by the swing and a big old rattlesnake was curled up in the corner," she remembered. During the Witchers' stay, she recalls that she and her husband redid the living room floor.

The home evokes images of ghosts and goblins. Especially in its current state of disrepair, it makes a pretty convincing haunted house. Jiminez remembers hearing many strange noises at night in the house -- the bumping and clawing of raccoons.

As for when the house was built, none of the former residents or city records can say. Photos and maps from 1935 clearly show the house despite the fact that a massive tornado leveled most of the buildings at Deep Eddy on May 4, 1922.

Eleven years without maintenance has taken its toll. The roof is collapsing and the windows are gone, but the city-owned house has sparked interest from people who wish to buy and move the structure. Maria Guerra of the city engineer's office says that will not happen. According to Ms. Guerra, the house contains lead paint and asbestos, and city policy forbids its sale.

On June 8, 2000, the Austin City Council approved construction of an EMS station on the site. The house will be razed.

The Restaurant

The red, white, and blue sign still beckons students and longtime residents alike who live and work in the area of 4700 South Congress. "Hill's Cafe" says one sign, and another taunts, "Home of the World Famous Sizzler." Paintings of covered wagons on the window and even a hitching post out front invite all.

On closer inspection, the windows are a bit dark and newspaper stands empty. The "World Famous Sizzler" hasn't sizzled since late 1988.

The Goodnight family had been associated with this South Austin location well before the restaurant opened. The family purchased the area in 1937, primarily because of high ground (hence the name Hill's), according to Dean Goodnight. The massive Colorado River flooding of past decades was one thing the Goodnights did not want to encounter. The first business on the spot was a gas station and grocery store. It was soon followed by the Classic Inn in 1940. From 1947 until its closing, Hill's was a South Austin landmark.

South Congress was the main route to San Antonio at that time until I-35 was completed. Despite a fire in 1957 that closed the business for two weeks, the cafe took care of customers in the 15,000-square-foot space with a western motif.

Since the restaurant closed, Goodnight Properties has used the front of the facility for real estate offices. The rest of Hill's has remained empty with the furnishings still inside waiting for diners. Boomer Goodnight managed the facility for more than half its life. When he decided to leave the industry, Goodnight elected not to sell to another food establishment because he wanted to be sure new management would not offer poor quality and sully the location's reputation.

Hill's is soon to leave the list of Abandoned Austin with a reopening scheduled for this spring, as radio host Bob Cole and Bastrop barbecue restaurant owner Steve Cartright bring Hill's Cafe back to its former glory.

"It will be what I think people expect from what was Austin's oldest restaurant." Cole said. New to Hill's old customers will be a family room, a bar, and live music space in the back. The restaurant will not be a duplicate of the old, but will bring back the five best-known menu items: chicken fried steak, yellow cream gravy, salad dressings made from scratch, homemade yeast rolls, and yes, the World Famous Sizzler.

The Tracks

As rail has been considered for Austin's future, a few remember the Missouri-Kansas-Texas tracks that ran from Georgetown to Austin. When the tracks were first used July 14, 1904, the towns of Pflugerville and Sprinkle joined the golden age of railroads.

During the 72 years the Katy (as it was nicknamed) rode the tracks, she saw Austin grow. She saw young Texans in uniform boarding the trains to fight in Europe, then saw the sons of the soldiers fortunate enough to return leave to do the same 23 years later. She also saw cars and trucks grow from overgrown toys for the rich and mobile into the death knell for passenger rail in Texas.

When, in July of 1964, the Katy lost the contract (to a trucking company) to carry mail for the U.S. Postal Service, she also discontinued passenger service from Dallas to San Antonio. In 1976, the railway was abandoned as a mode of transport, but the tracks remained.

The foundation of the Sprinkle station, which closed shortly after the post office closed in 1940, can still be seen today at the intersection of Cameron and Sprinkle Cutoff roads.

In Pflugerville, part of the railroad grade is a portion of the city's hike-and-bike trail network. The trestle over Gilleland Creek is visible near the historical marker. Like Sprinkle, Pflugerville's passenger depot also closed before passenger service ended. By the time the service made its last passenger run, the one-hour, 14-minute trip from Georgetown to the Austin station near the present corner of Third and Congress was nonstop.

Michael Jones, manager of rail planning and projects at the Texas Railroad Commission, remembers the trips on the tracks as very bumpy in the final days. The Katy did not have the resources for upkeep in her last days of passenger service. In 1988, the Katy was purchased by Union Pacific Railroad, ending the Missouri-Kansas-Texas railroad nationwide.

Evidence of the tracks is easier to locate in some places more than others. In some locations, new homes and roads have completely covered where the tracks once were. But in other places, the visible track makes it easy to imagine the Katy rolling through. Just look a little closer; an occasional railroad spike can be seen alongside the old tracks.

The Kiln

The story of Peter Calder Taylor began some 80-100 million years ago.

A shallow sea once covered most of Central Texas. As the prehistoric life forms died, their bodies fell to the floor of the sea. Once the sea retreated to its present location, the centuries of birth, death, and decay created limestone. As humans replaced the dinosaurs, the limestone was used for construction. Through the process of kilning, the limestone could also be used for cement to hold larger stones together.

Peter Taylor was born in Scotland in 1829. In 1860, he started in the limestone business in San Antonio in what is now known as the Sunken Gardens.

Limestone kilns were limited in their usage because of the intense heat from the furnaces. The kilns would need a break so that the structure would not sustain heat damage. Taylor patented the triangle braces used to reinforce the kilns, and in 1871, opened his Perpetual Lime Kiln in what is now west Austin. By 1874, he had 10 employees plus 20 horses and mules.

Taylor died Nov. 11, 1895, and the kilns closed soon after. The land was sold for residential development on the riverfront.

In 1954, Mrs. Fagan Dickson gave part of Taylor's old property to the city for what is now Reed Park on Pecos Drive. On May 7, 1983, a historical marker was dedicated to Taylor's innovation.

Taylor Slough is now a harbor for some of the high-dollar homes on Scenic Drive. A small rail car that was used to move the rock from the slough to the kiln is still visible.

The quiet neighborhood must have been a huge contrast to the way things were in the last half of the 19th century. According to a pamphlet published by the West Austin Neighborhood Group, Taylor had a blacksmith shop, a carpenter shop, a wheelwright, and a painter's shop, plus a 175-foot-long shed. Add to that 40 to 50 employees making 50,000 barrels of lime cement per year, and the neighborhood was more an industrial park.

Most of the evidence of this early industrial center is long gone, but the kilns are still standing. One is in Reed Park; the other is on Scenic Drive near Cherry.

The Athletic Club

The movie The Sixth Sense dealt with people who are stuck between worlds. The lost souls had died, but were not ready to move on to the next plane. If a screenplay were written about the Austin Athletic Club, the plot wouldn't be too different.

The three-story, wood-frame building at Lamar and Shoal Creek is passed by thousands of Austinites every day. The paint is peeling, and the floors and roof are sagging. The windows and doors have been boarded up ever since its closing in January 1987.

The Austin Athletic Club began life with the Austin Parks & Recreation Department in 1931. Tennis, exercise classes, dancing, crafts, volleyball, and the annual play were all diversions to an Austin about 1/10th the size it is today. In 1971, the name was changed to the Austin Recreation Center. Its location near Shoal Creek made for easy access to other parks, but also sealed its fate.

In May of 1981, the normally slow trickle of the nearby creek turned into a raging river. Homes, businesses, cars, and people along the floodplain were hit and hit hard by the Memorial Day Floods. The dressing rooms of the rec center were damaged and plans were soon drawn up for a new ARC.

"The design for the new [ARC] reflects the flooding," according to Stuart Strong, division manager for the Austin Parks & Recreation Department. He said that the plat note for the very same replacement ARC includes plans for the old one to be torn down.

So why is the structure still there? "The issue is funding," Strong said. Funds were never approved by the city to demolish it, so "Austin Athletic Club" still looks down on motorists passing down West 12th and Lamar. The peeling paint, sagging roof, and graffiti in some ways make it appear to have been abandoned much longer than 14 years, but memos from the Eighties are still affixed to the bulletin boards. Meanwhile the new ARC stands farther from the creek and on piers.

The Rock

The Ben Howell Memorial Trail is probably used now more than ever. Dogs, joggers, and Travis Heights Elementary students alike are constantly traveling up and down the trail that runs along Blunn Creek through Stacy Park.

The South Austin Lions Club broke ground for the trail on Feb. 12, 1967, to honor a former member through a gift to the community. The trail, the heated pool built by the WPA during the New Deal, and the fountain all take advantage of the water resources of the area.

Fountain? There's a fountain at Stacy Park, you say? Can't visualize it? Well, just go to the swimming pool parking lot and look toward the creek. Two ornamental fences mark the spot where there once was a birdbath-shaped fountain dedicated by the Lions in the late Sixties.

Stacy Pool is filled with warm water from a well beneath the park. Back in the fountain's day, overflow from the pool gurgled under the parking lot, down a manmade ravine, into the basin where bushes now grow, through the rust-colored stone, and up the fountain.

The well's water level had dropped significantly since 1975, according to a memo from Assistant City Manager Joseph Lessard to Council Member Max Nofziger, who requested information on the fountain in July of 1989. "At the present, the well is only identified by a mound of concrete and a broken pipe," Nofziger wrote. "This sign could be made into a fountain with signage explaining the springs [thereby making it] an attraction rather than an eyesore."

Lessard wrote back to Nofziger about other problems: The pipes were probably corroded, and new valves would need to be installed. The high mineral content of the water would continue to stain the stones around the fountain, maintaining its rusted look. Lessard estimated that the cost of plumbing repairs would be $4,000, and that a new sign would cost another $1,000.

For now at least, the fenced-in rock sits, lending a mythical air to the place. Was it a ceremonial stone for Comanche rituals? Did Sam Houston pull a sword out of the stone and then hear a voice telling him how to defeat Santa Anna's army? Make up your own story to tell out-of-towners ...

Robertson Hill

The future of one particular empty hill in east Austin has been a subject of much scrutiny. What to do with it? Affordable housing? Jobs for east Austin? Convenient shopping? Pedestrian mall? How this piece of real estate can work best for the city's future has been discussed, planned, and debated to death. But what about its past?

The hill in question is Robertson Hill. The neighborhood that is now known as Robertson Hill lies between East 11th and East 12th Streets. South of 11th Street is today's Guadalupe neighborhood. The hill was named for the family that owned the old French Legation for 99 years.

The Robertsons' home was built in 1841 and is now operated as a museum -- for years it was a dump. The area just north of the Legation bounded by East Ninth, I-35, San Marcos Street, and East 11th now sits empty save for one solitary live oak that seems to have been growing there since Henry Madison built his cabin around the time of the Civil War.

By 1875, the area had become a mostly African-American community (official segregation in Austin wasn't instituted until 1926). In 1877, Samuel Huston College (no relation to Sam Houston) opened its doors on East 11th -- six years before the first Longhorn went to class. Almost a decade later, 1884 saw the construction of both Ebenezer Baptist Church and Robertson Hill School on 11th Street.

After World War II, homes filled the area. The 1950 city directory shows a sharp contrast between the old and new. This particular stretch of 10th Street was filled with residents; now it is little more than crumbling pavement. During the same decade, Samuel Huston College merged with Tillotson in 1952, and the YWCA quickly took over the building. Byrd's Grocery was at Ninth and San Marcos. The 1955 directory started to show things changing for the area. Most of the homes on the south side of East 10th were vacant, and by 1960, roughly half the units occupied in 1950 were still listed.

Van Johnson, executive director of the East Austin Economic Development Corporation, said the building of I-35 had a lot to do with the change. The development of highway systems reinforced segregation, especially in the South, he asserts. "African-Americans saw [I-35] as an economic barrier that prevented the economy from the west to share with the east," he added. By the time the 1980 city directory was published, a mere five homes were listed. In the mid-Eighties, the few remaining homes were moved or razed as real estate broker Delbert Bennett purchased the land for a mall. In 1991, the Austin City Council gave permission for the mall, but instated a two-year deadline for construction to commence. As 1993 came and went with no sign of a shopping center, the land remained empty.

This particular stretch of land, now known as the "Bennett Tract," is now, at the turn of a new century, again the subject of speculation. The Riata Corporation has plans for a 1.3 million square foot mixed-use development. Matt Mathais of Riata is still working on the final design. Possibilities include a mixture of residential and commercial, with the possibility of a hotel and retail space.

The Guadalupe neighborhood and other Eastside neighbors object to the size of Mathias' plans, just as they objected to the mall property proposed by Bennett, which is one of the reasons this land remains empty. The neighbors, Mathias, and the city have been in mediation and discussion over these plans for almost a year.

The Hog Farm

Another empty parcel poised for development lies between Lakeline Mall and Cedar Park. Despite the rapid growth of the area, this area looks like it leapt right off the pages of the book Ghost Towns of Texas. Empty buildings sit on the land, providing stark contrast to the burgeoning Bell Boulevard right across the street. The vacant land is a stubborn reminder of a time gone by. Locally, it's referred to as the "Hog Farm."

The Hog Farm?

The State Hog and Dairy Farm began when the state of Texas purchased 307 acres from Ellen and N.J. Dedear in June of 1942. The state-raised hogs and dairy cows for the production of milk and meats for the Eleemosynary Institutions -- now known as the Department of Mental Health and Mental Retardation (or MHMR).

Residents of the institution worked on the farm as laborers taking care of the livestock. As a result, state institutions were self-sufficient, at least when it came to food.

Things changed in 1970, when the contract for food production was outsourced. The name of the facility was changed to the Leander Texas Rehabilitation Center. The rural setting of the location provided the perfect setting for another MHMR project, and the area was converted into a campground for the clients of the institution.

Former director Roy Jones enjoyed his tenure there. "The big enjoyment I got was seeing how the clients reacted. They [would come in from the outside] real tense, then [once they were at the campground for a while] have a smile on their faces," he said.

Camping, fishing, horseback riding, and a petting zoo made the area look less like a state facility and more like a Hill Country getaway.

The State Legislature in 1987 transferred the land from MHMR to the Texas Department of Transportation, but it remained under MHMR management. The campground was still used despite the area becoming less and less bucolic. In late 1993, the facility closed. Part of the old Hog Farm is being used as right-of-way for the new U.S. 183-A toll road.

The area made news on March 30, 1998, when Pohl-Brown & Associates brokered the purchase of the land for $18.3 million and won state approval, against the City of Austin's vehement objections, to zone the land to accommodate a new development the size of downtown Austin, which most folks expect will never actually be built. It is a safe assumption, however, that with its proximity to Cedar Park, Leander, northwest Austin, and Round Rock, the old State Hog and Dairy Farm will never be the same.

The Dog Park

It's one of those views straight off a postcard. 1012 Edgecliff Terrace, the plot at the northwest corner of Riverside and I-35, is a picture-perfect hilltop setting that overlooks Town Lake and the Austin skyline. Home to that incredible view is a boarded-up bungalow and a fenced-in dog park.

Ever since Hugo Kuehne built the home for Ollie Norwood in 1922, the home has been associated with big dreams. The three-acre site once included a Japanese teahouse, a fountain, a gazebo, and a swimming pool (an extremely rare luxury at that time). The home, along with a smaller home that is no longer there, was built as a private residence.

Norwood's sister, Beatrice, was a dreamer. She went to New York and performed as a Zeigfield dancer, came back home to Austin and lived at the home for a time, and then went on to become one of the city's most successful female real estate developers.

In the early Sixties, the Norwoods sold the property, and the home became the offices for Western Publications until about 1984, when, in the height of the real estate boom, developers dreamed of turning the hilltop into a complex of condos. To accommodate this vision, the house was moved to the empty field across Edgecliff Terrace. The South River City Citizens, the area neighborhood association, thought this dream sounded nightmarish, so they stepped in and successfully fought off the condos. In 1985, the empty hilltop and swimming pool below it became parkland when the city purchased the tract.

A new organization, Austin Women's Chamber of Commerce of Texas, took interest in the house. They had yet another dream. They figured that a resource center for women entrepreneurs and women starting careers would be a great addition to the city. And what better place than right at the gateway of Austin in a historic home associated with an Austin businesswoman? The plans included a design for the pool area to become a sculpture garden of prominent Texas women.

"When we took over the facility, it was very run-down," said Rose Batson, president of the chamber. The group's first goal was to move the house back to its original location. Through several fundraising efforts, the house was moved back onto the hill in 1999. Moving a house -- even across the street -- is no simple task. For example, when the site was being prepared, crews discovered a basement, so the ground had to be made more stable. An additional $1.2-1.3 million was estimated to get the house and resource center completed.

Despite the house being on city property, the city did not waive any fees or provide matching funds for the restoration. "We had support from the community, neighbors, and businesses," Batson says.

Unfortunately, the board of the Women's Chamber of Commerce grew weary of the project. "They felt it was not a productive use of time for a property we will never own," according to Batson.

In September 2000, the Women's Chamber made it official: They would no longer be involved with the restoration. "We poured our heart and soul into it. It was very painful to pull out," Batson says. Austin PARD has no plans at this time for the home's future.

For now, the home is back in its original spot, boarded up and covered with graffiti. The few acres surrounding it are now home to a popular dog park, where masters of canines let their pooches run wild and free in a self-contained, fenced enclosure.

"Whatever the city does with this property, [the best option] is to have it restored in a way that works with the neighborhood," Batson says. "I don't know why they won't invest in this beautiful place." ![]()

-- Devin Greaney

Sources: The Austin History Center and Austin Public Library; "Whatever Became of Sprinkle?" by Marguerite Jarrell; "Texas Railroads: A Record of Construction & Abandonment" by Charles P. Zlatkovich; the Austin Parks & Recreation Department; The Handbook of Texas Online; The Katy Railroad Historical Association; The Texas State Archives; the archives of the Austin American-Statesman; and the archives of The Austin Chronicle.