Letters at 3AM

Something Absurd in Between

By Michael Ventura, Fri., July 3, 2009

It was such a simple song. It said such a simple thing: "I want to hold your hand." An impulse basic as lust, or maybe more basic: contact; the acknowledgement of one for another, two together, the beginning of everything – clasped hands.

"And when I touch you, I feel happy inside." Just like that. Everybody had felt it. Everybody knew it was true.

And the song was everywhere. Even on that ferry to Riker's Island prison. Unembarrassed, childishly happy, the song tinkled from a plastic AM radio the size of a lunch box, as though four wee Beatles trilled in a tin can. Not much is bleaker than a prison or a ferry to a prison, and yet, even there, the song reminded you that there's such a thing as joy.

You boarded the ferry before dawn with cops and guards and who knows who in that winter of 1964. It was rarely as warm as 30 degrees. Wind blew through the river's corridor, encasing you in unspeakable coldness. I was 18, working in the prison mail room, in the special darkness that was Riker's, an atmosphere thick with violence and bewilderment. The song insisted that life was wonderful anyway.

When you work in a prison, its despair sticks to your clothes and your spirit. A weekend isn't enough to air you out – except this particular weekend in February. The Beatles landed on Friday, to play Ed Sullivan's live TV show Sunday. That weekend, New York City – a tough, gray, combative place in those days – was not itself. On subways and in diners, people smiled and spoke to one another. About the Beatles. "I Want to Hold Your Hand" played constantly, and we, momentarily, were different – but in a way that felt, to me, oddly familiar.

Not three months before, John Kennedy got himself shot dead. That day, and for days after, in diners, subways, and on street corners, folks spoke to one another suddenly, intimately, sharing the weight of the moment. This Beatles weekend was like that, but instead of mournful, it was giddy.

It seemed to me, at the time, a large thought: Beatlemania would not have been possible without the Kennedy assassination. The response to the assassination created, as never before, a template of media-instigated, media-connected mass feeling – a kind of receptacle into which we poured our insecurities, grief, fears, failed hopes. Once created, that template didn't go away but awaited another blast of similarly intense input, and the next was the opposite of the first: Beatlemania was a receptacle into which we poured everything joyful, forgetful, hopeful, and, because the template was the same, the public response was the same: Strangers everywhere spontaneously shared the buoyancy of the moment.

I felt, in that thought, that I'd gleaned something about how the world feels itself to be "the world" – the illusion, that is, of "the world" as a purposeful entity. But a striking aspect of such an insight is that, while fun to ponder, it's completely useless. As an 18-year-old would-be poet, I jotted down my thought and turned up the radio for the next hit.

Musically, the decade was taking off. Beatles songs ran up and down the charts alongside the Drifters' "Under the Boardwalk," the Beach Boys' "I Get Around," the Righteous Brothers' "You've Lost That Loving Feeling," the Kinks' "All Day and All of the Night," the Zombies' "She's Not There," Martha & the Vandellas' "Dancing in the Street," the Temptations' "My Girl," the Animals' "House of the Rising Sun," Them's "Gloria," Sam Cooke's "A Change Is Gonna Come," and Bob Dylan's "The Times They Are A-Changin'" – as though the music knew something was up, something was coming, something exciting and maybe scary, a break with the past that many would celebrate, many would regret, and a few would do both. I don't think it's only in retrospect that underneath it all one felt a great and trembling poignancy. What is poignancy but the feeling of "hello" and "goodbye" at the same time?

When A Hard Day's Night came out that summer, I saw it with a half-dozen or so friends, gals and guys, at a theatre in Mahopac, N.Y. A Hard Day's Night was verbal and visual slapstick in gorgeous black and white, the songs all hope and light, and the faces of the Beatles so familiar by then that it had the feel of a home movie – somehow (this was their magic), they were us. Irreverent but sweet. Slyly hip but no threat. To absorb for the first time, with no preconceptions, A Hard Day's Night's happiness, its sense of possibility, its message that nothing could stop or repress such joy and that nothing would go wrong ever, the music as irrepressible as it was inclusive – it was too much for us!

We left that theatre so hungry for life that we did the only reasonable thing: In the hot night air, we ran, danced, and shouted all over Mahopac's graveyard, as though only the dead would understand our urgency to live. But there it was again: All this joy had something to do with death.

I know someone who saw that movie 30 times. Don't know how many times I saw it – six, maybe 10. And, I promise you, none of us registered the moment when Ringo said, wistfully, "Being middle-aged and old takes up most of your time, doesn't it?" (Yeah. It does.)

Dancing, yelping, and leaping over tombstones, I stood suddenly still – here was Beatlemania, death, and something absurd in between. Me! So I screamed, loud as I could, leapt atop a gravestone, balanced, whooped, and danced off, while the clouded moon and the future hovered like shrouded angels. I remember someone said, "The Beatles are heralds."

Sept. 20, 1964. I'd left Riker's Island for Times Square – at the time, there was no funkier neighborhood on the continent. I worked as a counterman at a diner on Eighth Avenue. Prostitutes displayed their wares in the window booths; cops came by for payoffs; an ex-Marine closet queen worked the counter with me – it was an education. When I'd get off work I felt, at last, that I had the right to walk the streets as a full sharer in life, earning my way, with no backup and no need of any.

That was me after a 12-hour shift, my pockets full of money as I walked to Seventh Avenue – a person of responsibility. My family depended on me. While friends wondered what to do with their lives, I had a task, which was more freeing than you might suppose. Serious life had begun.

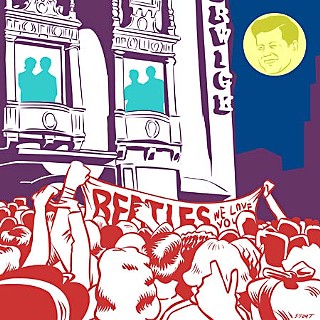

Only to become unserious in the extreme when I turned the corner and was swept into a mass of screaming virginal girls who filled Times Square, spilling into the streets, dragging with them all the usual denizens – cops, whores, hustlers, hoods, grunt workers like me. The girls had no idea where they were or what was around them as they teemed toward the Paramount's marquee, which was bright with "BEATLES TONIGHT!"

There was no resisting this mob, turning the corner east on 43rd, packed with girls, no traffic possible, all of them jumping up and down, screaming, pointing to two lit windows about four stories up. In each window were two shadow figures, silhouetted black against their room's light, easily recognizable by their hairdos. They waved to the happy masses.

I was as happy as anyone. I liked them best that way, as shadows, brightly backlit above that giddily maddened, funky, dangerous neighborhood. These were the Beatles of those first childlike songs, before they and the decade darkened, and they, too, became swept away by what they'd heralded.

I elbowed myself out of that crowd and walked crosstown to Grand Central Station. A big moon hung above the Empire State Building. And I thought of that moment in the graveyard, when I was even happier, and something – I can't exactly say what – had seemed incredibly clear.

It was some kind of way to be 18. A wild moment of clarity, useless in itself, but to be savored in memory.