Letters @ 3AM

Heartland

By Michael Ventura, Fri., July 6, 2007

Idly leafing through old travel notebooks, I came upon aged Verlie, who had sat beside me on the bus from Muskogee to, eventually, Wichita. It was very late; she couldn't sleep; she seemed in pain on that bus seat but didn't complain. You could smoke in buses then and we were smoking. At the last stop, I'd gotten her a coffee not knowing if she'd want one; she was glad to take it and started talking. She told me of being a girl on her family's farm in Arkansas, 1905-ish, grinding coffee beans by hand. Coffee came in 50-pound bags, "Green beans, roast 'em yerself, grind 'em yerself." She asked where I was from; I told her and spoke of my travels. She said (very satisfied to say it, too), "I just been to four states my whole life: Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, an' Texas." She spoke as though even four was too many and offered the opinion that a young man like myself "shouldn't be wanderin' aroun' so far from family." Birthed her first child in Arkansas at the age of 15. Bore six kids before her 51-year marriage was done; she'd been divorced now 15 years. (I didn't ask why she divorced after a half-century. I wish I had. I was new to the ways of such people and didn't know that Verlie wouldn't have mentioned such a thing if she didn't want me to ask; but, since I didn't ask, Verlie wouldn't volunteer.) She'd worked as a cook 20 years in Hominy, wherever Hominy was; I didn't ask that, either. "My sons like Tulsa real well 'cause they have inside jobs in Tulsa. I'm so proud they have inside jobs." Inside jobs. Anything was better than slaving on a farm. She said "t'oth'un," meaning "the other one." She said "the beautifulest thing" – about what, I neglected to write down. She asked what I did; I told her I was writing a screenplay. She asked what that was, and I told her. "I never cared much for shows," she said. Hardly ever went to shows, though her kids did. The show in her town finally closed a couple of years ago. "I liked t'go t'dances, jus' didn't like shows." Verlie's kids got her a TV, but she never watched it "'cept when they visit." Didn't watch TV, didn't read newspapers. "Papers, they're jus' 'bout trouble."

I wondered (not aloud) about Franklin Roosevelt, Woody Guthrie, Martin Luther King Jr., and further back to Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Abraham Lincoln – leaders, artists, and thinkers who could talk to Verlie. I wondered if we'd ever again have a liberal-ish politician or artist or thinker who could be bothered to speak to the Verlies of this land about the big things, the issues important to many of us. No point getting mushy about Verlie, no point seeing her limitations as virtues in themselves; still, Verlie's world was a world of the hands and the heart, and you can't do anything, on a large or small scale, without people of the hands and heart. If you can't somehow include Verlie, there's a lot in your program that will not get done, no matter how hifalutin your intentions. Verlie is of those who, in her phrase, "do the doin'." College kids and urban intelligentsia aren't enough; until a cultural innovation makes its way to Verlie, it doesn't stick. Which is what John Adams meant in his letter to Jefferson when he said, "The revolution was in the minds of the people."

Our bus stopped someplace called Durant. A teenager boarded; he wore a Cheryl Ladd T-shirt. People started talking across the aisles. The large lady bus driver. The old Chicano discoursing of bad kidneys. Verlie announced I was writing a "show." They all wished me luck. And all the while I was thinking, "Who speaks to these good people? Right-wingers seem to know how, but who on the left?" A crusty old farmer – work boots, creased and bony hands, sunburned neck and face – was reading a pamphlet titled "Government and God." Somebody was speaking to him, and it wasn't me, and it wasn't anyone I knew or valued. How do you expect people to go your way if you don't even deign to notice them? That farmer was interested. He was reading a pamphlet. If I'd written a pamphlet directed to him, in terms he could understand, chances are he might be interested and read it. If we ignore him, why shouldn't he ignore us?

"You want some gum?" another old fellow asked me, on the bus back from Wichita. It meant he wanted to talk. "Sure." I thanked him and chewed. He was from Quartzsite, Arizona. Well, it just happens I've had several important nights in Quartzsite, and a state patrolman almost jailed me there; I described the patrolman, and this old fellow knew him and didn't like him anymore than I. We talked about the sexy older ladies who ran Quartzsite's doughnut shop – fleshy, funny, savvy women. He said, "You could set your compass by gals like that." In the course of our conversation, he mentioned that you can't buy a daily paper in Quartzsite anymore. "They had a shortage of newsprint, so they cut out the outlying areas. They gonna come back; they said they will, soon as they have the newsprint. By that time, we'll be so used t'doin' without, we won't want it." We've cut out "the outlying areas" and left them to radio demagogues.

Another old travel notebook, from about that same time, describes a bar in Midland-Odessa and an older salesman named Tony. He said he knew the gangster who blinded labor journalist Victor Riesel with acid. "The guy [the gangster] got killed the next day." Tony sighed. "I shoulda been a hit man. I think about it a lot." He stated this dubious ambition in a wistful, dejected voice; Tony wasn't dangerous, but he wanted to be. Instead, he was regional sales director of his company, and that's as high as he would rise, because "I don't have an Anglo-Saxon name." Then: "I always get the feeling I shouldn't be doing what I'm doing, I should be doing something else."

If I had a dollar for every time some stranger on my travels has said something just like that, I could pick up the check for a large party at a very expensive restaurant. In a more or less free country, where (theoretically) you can do more or less what you please, many feel "I shouldn't be doing what I'm doing, I should be doing something else." They're told from grade school that they can go as high as they aim, while at the same time they see from the cradle that this usually is not so. But they can't help believing in the American Dream. When they fail its expectations and their own, they usually blame themselves – then they lay their old high expectations on their children, who disappoint their parents and themselves in turn. This longing, pain, and disappointment – this sense of "Oh my God, I've failed the dream!" – are basic to our way of life. Politicians, advertisers, and the entertainment industry play on these feelings for votes and profit, but for many people, nothing alleviates their secret sense of having failed. Edward Hopper is the most American of painters because he painted solitary Americans whose wistful sadness and preoccupied expressions say exactly, "I shouldn't be doing what I'm doing, I should be doing something else." Underneath America's manic activity, that's the saddest song on the great American jukebox – a song mostly sung to strangers, because if you say to someone you love, "I should be doing something else," it would be too threatening, too disruptive.

And this at Old Smokey's in Winslow, Arizona: An old working man in a tractor hat said to another old man wearing a similar hat, "I don't know much. I don't understand anything I know, let's put it that way."

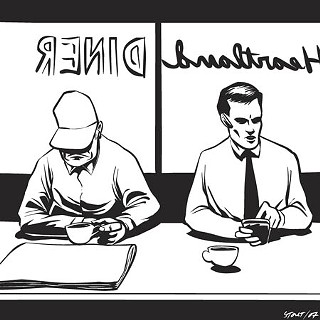

Beneath all our competing soundtracks and rhetoric, this is the true and secret American discourse. There is the cacophony of the "Public Discussion" (as a friend calls it in capital letters) and the longing and bafflement of the private discussions in our bars and diners and public conveyances. The craziness of this country is that the public and private discussions have almost nothing to do with each other.

But I also think of Butch telling me, "My grandad drove the first car to Lubbock" – drove it on a dirt road from Wichita Falls. Janette saying, "My grandad lived in a dugout in Palo Duro Canyon and built the first road in Palo Duro Canyon, from Claude to Wayside." Debbie recalling talks with her grandmother who came to the Texas Panhandle in a covered wagon. Or old Ruby, in Sweetwater, Texas, whose father was a trail boss and twice employed Billy the Kid on cattle drives. Perhaps that's why we're so confused – as a country, we're still young enough to know someone who drove the first car, built the first road, arrived in a covered wagon. One generation builds a way of life, and before they die, the next generation changes it utterly, so we remain congenitally young, eternally immature, baffled but pretending not to be, except maybe with a friend over morning coffee when we say, "I don't understand anything I know, let's put it that way." ![]()