Book Review: Setting the Table

Oversized books

Reviewed by Cindy Widner, Fri., Dec. 3, 2010

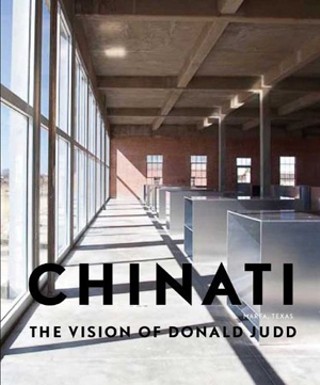

Chinati: The Vision of Donald Judd

by Marianne StockebrandYale University Press, 328 pp., $65

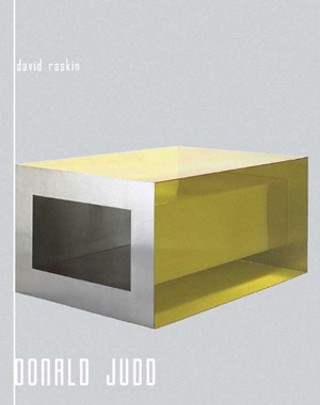

Donald Judd

by David RaskinYale University Press, 220 pp., $55

"White guys doing their thing in the desert" is how I once described the work of Donald Judd and friends at Chinati, the art compound Judd founded in Marfa, Texas. It was a flippant statement – one part dismissive, two parts defensive – meant to shorthand the precision-driven, isolationist, and sometimes colonizing (here I imagine my sunburned German ancestors tromping around New Mexico) severity associated with the Minimalism and land art of the 1960s and 1970s, particularly that work imbued with the kind of masculine subjectivity that never seems to go away completely.

It is difficult not to note that Marfa is a product of American expansionism. It is also difficult to ignore that Judd's work there – buying, reworking, and installing art in area buildings and ranches, first via the oil-moneyed Dia Art Foundation and later through the Chinati Foundation – is somewhat an extension of that colonial project. On the other hand, Judd did hand-deliver the dying town a 21st century tourist economy, way ahead of schedule.

But whatever. A version of this preamble runs through my head every time I set the cruise control for Far West Texas, which only makes my experience of Judd's Marfa work as pure pleasure more surprising. Invariably, I feel a start upon first glance, particularly of the rows of aluminium cubes in former artillery sheds, but also at the former Locker Plant (now a studio), or the bank building, almost completely untouched on the outside.

I felt the same start upon seeing Marianne Stockebrand's Chinati. It is, unbelievably, the first monograph on the project, and Judd's longtime collaborator and longtime Chinati Foundation director has captured the lush austerity of the artist's Marfa project with detailed narrative and subtle, gorgeous photographs that reveal the elements at play in the artwork. There are chapters devoted to each of the artworks at Chinati, as well as to Judd's other local work, with civic and geographic elements presented with such care and attention that they are inseparable from the art – just as Judd intended. You won't find a sentimental, community-minded Judd here – or probably anywhere – but there is ample documentation that, as completely practical and aesthetic matters, the artist strove to preserve the town's character, in addition to being a proto-xeriscaper and land preservationist.

For those discomfited by Judd's seeming contradictions – he created highly conceptual, formal, and repetitive pieces that somehow elicit strong feelings – David Raskin's Donald Judd offers a comforting thesis: He meant to do that. Raskin, a professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, pulls from Judd's work, his philosophical influences, and his essays the theory that underlies his art – essentially, that "art adds to our world by producing transitions rather than meanings," that art must be "interesting," and that "interest is biopsychological." If the news that, as Raskin writes of one of the artist's "horizontal progressions for the wall ... it is easier to understand and unique in terms of its math" comes as a letdown, the book also explores Judd's history, politics, and biography in a way that is both fascinating and dense, approachable and abstract – echoing the strangely affecting nature of the work itself.