Book Review: Readings

Larry Brown

Reviewed by Marrit Ingman, Fri., March 9, 2007

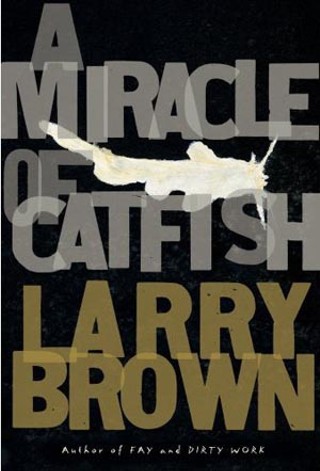

A Miracle of Catfish

by Larry Brown

Algonquin, 456 pp., $24.95

In that it is forever incomplete, Brown's sixth and final novel should arguably be exempt from criticism. Its flaws bear mention – when editor Shannon Ravenel relates, "He was, as a novelist, likely to write more than he needed," it's easy to agree – but the book Brown had almost finished when he died suddenly at home in Lafayette County, Miss., recommends itself even as a work in progress, with too much weight on the exposition and an ending not yet written.As it is, A Miracle of Catfish probably isn't destined for your beach bag. It's more of a study in form, beginning with a hand-drawn map of the setting and ending with notes for the final chapters and an epilogue. In between are fathers and sons and a stretch of land, Brown's métier, and the drawling rhythm of rural life: waiting for rain to start or stop, waiting for payday, waiting for fish to bite, waiting for the consequences of what you did wrong and can't hide. Cortez Sharp is a crusty old farmer with secrets in his barn, an estranged daughter in Atlanta, and a brand-new stock pond on his property. Just around the way lives Jimmy's daddy – that's how he's identified throughout the book – an irredeemable screwup and just-beer alcoholic with a curious and tragically neglected 9-year-old son, who's watching the pond for signs of new catfish.

Brown changes perspective often because he can, slipping from one voice to another without a wobble – including crows in a tree, a puppy, and the first-person narrative of a bulldozer driver. Not all of these impressions are necessary to develop the book's remarkably textured sense of place; in some cases, Brown has written more than he needed. Just the same, the depth of the book's characterizations rewards a reader's patience, and Brown's plainspoken but elegant prose craft is a cozy vehicle for some of the more gothic touches in the story. Such as the ghost.

Ultimately it is the unflinching but humanistic observation of rural Southern manhood – the hopes and betrayals of kinship, the frustrations of poverty and thwarted success, the seemingly inexorable pull of poor decisions, the urge to protect that can become violent – that will define Brown's body of work. Miracle, too, is at times a melancholy read, driven as it is by the yearnings of children and fathers and old men to do right despite their deep flaws. No resolution exists, but Brown's final chapters suggest the possibility of redemption and reconnection.