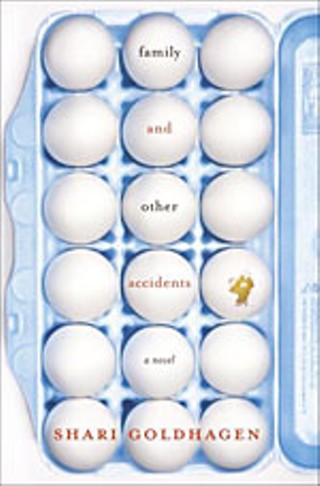

Family and Other Accidents

Reviewed by Nora Ankrum, Fri., April 14, 2006

Family and Other Accidents

by Shari Goldhagen

Doubleday, 272 pp., $23.95 (simultaneous paper release: $14)

Shari Goldhagen's Family and Other Accidents is a book about people who don't share their feelings, and while there's something depressingly realistic about them in that regard, they still never quite feel real. The story begins two years after the deaths of the Reed brothers' parents, which left Jack, at 25 years old, to be the guardian of Connor, his 15-year-old brother, and the meat of the novel is in the disconnect between these two reticent siblings. As the chapters switch points of view between them – out of necessity, since you'd never understand one brother if you only had the other's observations to go on – they also jerk you through the years in fits, starting when Connor's still in high school and Jack's a lawyer newly resigned to his father's footsteps, and ending when Connor's own daughter hits driving age.

The intervening years find the brothers alternately keeping in touch or not and alternately getting along with their various girlfriends/spouses or not, which is also realistic yet unreal, perhaps because Jack and Connor feel as distant from the reader as they do from each other. Goldhagen has a talent for presenting matter-of-factly how lives and relationships sour and spin out of our control. "Months before the dog starts dying," she writes, "Laine feels the already-wide distance between her and her husband getting wider, but neither of them mentions it."

But because she doesn't bother with reasons in this world where Connor's wife, Laine, can feel a distance at the outset of chapter 10 that didn't exist years earlier, or inches away, in chapter nine, there's a sense of hopelessness here that never lifts, even in the final pages when we finally see Jack express a few feelings and we see our heroes truly seeing one another. This is the appropriate resolution: People too absorbed in their own pain finally see past their feelings to those of someone else. But the journey there feels static and far away, an endless repetition of the characters' inexplicable unwillingness to stake a claim for themselves, to ask of each other what each really needs. So when we finally do get our resolution, it truly does feel like an accident – again, realistic, and again, somehow too removed to feel real.