Summer Reading

Ian McEwan's observation of human experience is unflaggingly acute

By Ameni Rozsa, Fri., May 27, 2005

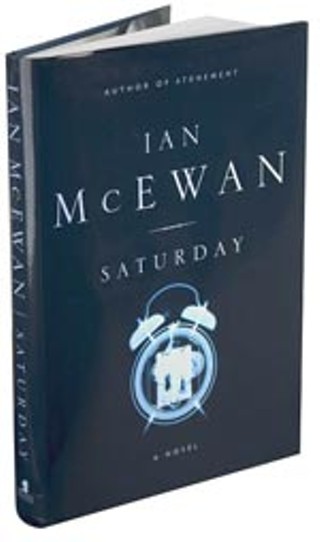

Saturday

by Ian McEwan

Talese, 304 pp., $26

Ian McEwan's observation of human experience is unflaggingly acute. Take, for example, a moment from his latest, which follows neuroscientist Henry Perowne through the events of a single day in February of 2003. Perowne's driving to a squash game, reflecting on the protest march that has blocked a main thoroughfare. His mental wanderings are familiar enough, but the way they've been slowed down for our examination is characteristic McEwan: "The world probably has changed fundamentally and the matter is being clumsily handled ... there'll be more deaths on a similar scale, probably in this city. Is he so frightened that he can't face the fact? ... He experiences [these questions] more as a mental shrug followed by an interrogative pulse." McEwan captures perfectly the way we think to ourselves. In fact, so absorbed are we in Perowne's mind that when he finds himself in a car accident a moment later, we are as startled as he is. McEwan deftly diagrams the crash at the same time that he preserves its stomach-churning swiftness, "the snap of a wing mirror cleanly sheared and the whine of sheet-steel surfaces sliding under pressure." So commences the unsettling crescendo of the day, which, in true McEwan form, must eventually include a direct confrontation with horror. Writing this precise has the dual effect of calling attention to the author's gifts at the same time that it self-effaces. Really, it seems to say, anyone could do what I've done here, if only they took the time. So we follow along cheerfully as McEwan invokes the big questions: Where does evil come from? What is to be made of chance? What is the function of art? Like his surgeon protagonist, McEwan is calmly dispassionate but never disinterested. Breathtakingly exact, his prose cuts into everything from brains to literature to war crimes to blues music. The author, like the surgeon, is never happier than when he's engaged in the process of this opening-up; the reader, like an observer in an operating theatre, can't help but be fascinated by what the good doctor is showing us: experience, so bloodless yet so gorgeously alive.