Book Review: Readings

Julie Orringer

Reviewed by Michael Schaub, Fri., Oct. 10, 2003

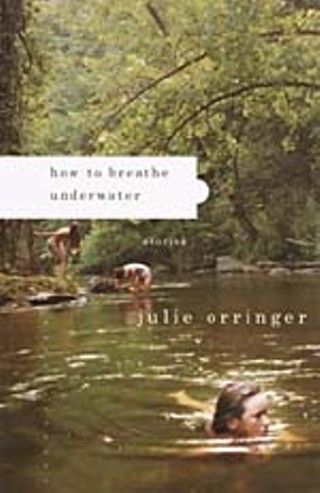

How to Breathe Underwater: Stories

by Julie OrringerKnopf, 226 pp., $21

At every record store in America, there's a middle-aged guy (it's always a guy) who is only too happy to inform you that rock & roll died sometime between the year he lost his virginity and the year you were born. A close cousin to this specimen is the literary critic who periodically awakens from an irrelevant slumber to pronounce -- again -- the death of short fiction, which apparently expired the second Raymond Carver typed the last period of Cathedral.

But I guess nobody told Julie Orringer that, or else she just forgot to care. The nine stories in How to Breathe Underwater are so beautiful, so wise and vital, it should (but won't) shut the boomer literary establishment up for good. Orringer, who is 30, belies the old bromide that young people can't write about youth convincingly. The children and young adults who form the backbones of these stories are achingly real and (very) painfully alive.

Take, for instance, the adolescent narrator of "The Isabel Fish." Maddy is taking scuba diving lessons at the urging of her parents, despite her near drowning months before in a car crash that killed her brother's girlfriend. "It's impossible to believe how gone she is, how untouchable," Maddy reflects. "She's the only one who doesn't have to know what it's like here on Earth without her." It sounds so simple, so obvious, though it's anything but.

In "Pilgrims," the children of dead or dying mothers spend an apocalyptic Thanksgiving cruelly teasing one another, until the unthinkable suddenly, and perhaps inevitably, happens. The specter of terminal illness also turns up in "What We Save," in which young Helena contemplates her mother's battle with cancer while having a miserable time at Disney World. "She'd imagined her mother's organs going through a kind of re-forging," Orringer writes, "a kind of mystical cleansing, after which they'd start their lives again in Helena's body -- her mother's sick breasts becoming Helena's new healthy ones; her mother's ovaries, reborn, shooting estrogen into Helena's bloodstream."

The act of growing up is often a heroic struggle in itself, and Orringer recognizes this, treating her characters with compassion but not an ounce of condescension. These stories are edgy, but it's an earned edginess, realistic and uncaricatured. This becomes especially apparent in the final story, "Stations of the Cross," which culminates in a shocking passion play gone horribly awry. It's impossible not to feel for the pained and alienated young women in Orringer's stories, and impossible not to be stunned and moved by their quests for redemption. More so than any debut author in recent years, Orringer proves that the kids are all right, even when they're not.

Julie Orringer will be at BookPeople on Friday, Oct. 24, 7pm, with Vendela Vida, author of And Now You Can Go (for Kate Cantrill's review, see austinchronicle.com/issues/dispatch/2003-08-29/books_readings2.html).