Book Review: Readings

Ryszard Kapuscinski

Reviewed by Shannon McCormick, Fri., July 20, 2001

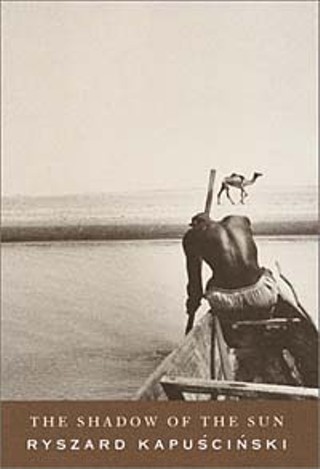

The Shadow of the Sun

by Ryszard Kapusinski; translated by Klara GlowczewskaKnopf, 325 pp., $25

For those of us inclined to complain about the blight of American-style capitalism on other cultures, Ryszard Kapuscinski's latest book is a reminder that we're not the first bullies in world history. Nor is the current globalism the only one that has ever existed. It may be strange to think of Europe after reading a book dedicated to Africa and Africans, but one of the strongest impressions left by the book is the shameful legacy of European colonization and exploitation of the continent. That this 500-year period, one of the darkest chapters in human history, came to its nominal end within living memory of many of the readers of this paper should give us pause the next time a country like France chooses to lecture us about our less-than-perfect international record.

Of the two biggest geopolitical shifts in the post-World War II era -- the advent and demise of the Cold War and the decolonization of Africa and Asia -- it is the latter that seems of greater historic import at this date. And the growing disparity in wealth between Western nations and those of the Third World poses a greater long-term threat to global peace and stability than any old-fashioned, 20th-century clash of political ideologies. To understand the vicissitudes of these cultural forces on the lives of everyday Africans, there is probably no one better to turn to than Kapuscinski. A Polish foreign correspondent, Kapuscinski has been covering Africa and other neglected corners of the world for the past four decades. He has witnessed 27 coups and revolutions, been sentenced to death four times, and has seen Africa in the post-colonial era descend into violence and the horrors of AIDS. This is not to imply he approaches Africa stereotypically, but Kapuscinski isn't inclined to euphemism.

The Shadow of the Sun is a collage-like collection of memories culled from these four decades of correspondence. For those interested in a comprehensive overview of recent African history and politics, this book is not the best place to start, although the chapters on Rwanda, the Sudan, and Liberia are all particularly informative. Rather, the book's strong points are the intimate details from Kapuscinski's personal experience: a hotel room covered in turtle-sized cockroaches, the body-shaking tremors of malaria, the sad eyes of an elephant loose in a campsite. At times the book's loose structure is frustrating -- often, just as he arrives in a village after an arduous journey, he ends the chapter and leaps years and miles away to yet another story. But Kapuscinski writes about Africa and her people with an empathy and sensitivity that one might wish his European forebears had possessed.