The High Life

Amanda Foreman Takes on Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire

By Amanda Eyre Ward, Fri., Feb. 2, 2001

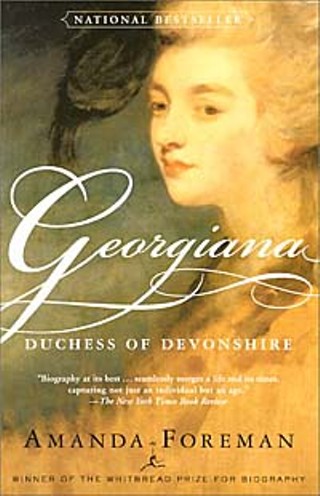

Imagine Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, preparing for a night out on the town. It is 1775, and she has fashioned a three-foot tower on her head, using scented pomade to affix pads of horsehair on top of her own hair. She has just thought of the idea of making tiny wooden ships to adorn her horsehair wig, and has called to her servants. It will take the help of at least two hairdressers and many hours to create Georgiana's sensational hairdo, and yet, notes Amanda Foreman in her riveting biography, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (Modern Library, $15.95), soon after this fateful night, "women competed with each other to construct the tallest head, ignoring the fact that it made quick movements impossible, and the only way to ride in a carriage was to sit on the floor."

Envied, imitated, and always observed, Georgiana was as famous as her great-great-great-great niece, Lady Diana Spencer, would be. Georgiana's marriage in 1774 to the Duke of Devonshire cemented relations between two of the richest families in England, and Georgiana's life took place against a backdrop of palaces and ballrooms.

A typical night for Georgiana, Foreman explained in a recent interview from her home in New York, began with food: "They would begin the evening with a great feast, and then they would go to the opera, watch perhaps the first three acts, and then go back to someone's house and feast again. They would eat lots of game: venison, sides of beef. They drank enormous amounts, wine mostly, this claret that British love, red wine. They would eat at seven, and then again at midnight. They had no heat in these days, just the heat from fireplaces, so it was extremely cold. I didn't understand how they could possibly eat so much, but they were burning all these calories just keeping warm. You have to realize, these people had no jobs. They didn't really have anything to do, and so they gorged themselves."

Georgiana was known to turn her enormous home, Devonshire House, into a casino, complete with professional dealers and banks more than willing to lend money to London's tony set. "These were very serious gamblers," says Foreman. "People threw up from the stress. You imagine ladies playing cards like in a Jane Austen novel, very sedate, but in fact, they were doing very heavy gambling." Georgiana's game of choice was called faro. "Faro is a game of chance, essentially, with no skill involved," explains Foreman. "You bet against the bank, and the bank almost always wins. Georgiana became addicted to the game, and it was very tragic in the end. She would let the bankers set up in her drawing room in exchange for a percentage of the profits. But of course Georgiana was so addicted that she would gamble too, and end up basically getting a percentage of her own losses back."

Georgiana would go on to lose millions of dollars, to miscarry repeatedly, to bear an illegitimate child and three legitimate ones. She would endure a lifelong marriage to the Duke, a man who, according the tabloids, was the only man in England who did not love her. She would be courted by the Prince of Wales (whom she called "Prinny"), and would become instrumental in leading the Whig party to power. She would fall in love with Lady Elizabeth "Bess" Foster and share her with the Duke. (The three lived in a menage ô trois until the end of Georgiana's life.) But imagine her before all this, surrounded by servants coating horsehair with pomade, sipping claret, and smiling to herself at the giddy pleasures the evening holds for her.

Amanda Foreman makes it simple to imagine Georgiana in such a flattering light. "Biographers," Foreman notes in the introduction to Georgiana, "are notorious for falling in love with their subjects." Too often regarded as dull compilations of dusty facts, biographies are rarely bestsellers. But Georgiana reads like a racy novel, complete with enough rocky relationships, torrid trysts, and illegitimate childbirths to keep Jerry Springer in business for weeks. In fact, the American version of Georgiana (which, Foreman admits, omits historical facts that "Americans wouldn't give a monkeywrench about") is proving to be just as successful as the British version.

"I was a graduate student at Oxford when I discovered Georgiana," Foreman explains. "I was supposed to be writing about attitudes to race and color in late 18th-century London. As part of my research, I was reading a biography of Charles Grey, who, as a young man, proposed the motion to abolish the slave trade. The biography also referred to his tragic affair with Georgiana and quoted some of her letters to him. But the way the biographer referred to her, dismissing her as some inconsequential, rather sad figure contrasted -- and I felt wrongly -- with the brilliance of her letters. And from then on I just kept thinking about her, convinced that someone was wrong, and that this woman whose words had so moved me had clearly been mistreated. I started to neglect my thesis to the extent that one day I realized I'd spent six months reading about Georgiana and doing nothing on my doctorate at all! So I went to the authorities and threw myself on my knees and said, 'Please, please will you let me change my subject and write about her?' Fortunately for me, they agreed."

Foreman talks about being an overweight grad student spending her formative years in the library stacks ("I've never even been to a keg party," she notes wistfully), and while she talks, I look at the publicity photographs splayed across my desk: Foreman, dressed in a glamorous period dress for an Elle photo shoot, Foreman in a fabulous bronze, low-cut sheath accepting the Whitbred Prize for Biography of the Year, Foreman, her platinum hair shining against her black leather jacket in her author photograph, and most notorious, Foreman posing nude behind a pile of books in a Tatler article depicting up-and-coming Brits with their bare necessities. I mention the discrepancies between the picture she paints of a shy bookworm and the articles that call Foreman "the glamorous biographer who is taking London by storm." As Georgiana would do, Foreman only laughs. "Well, I would like to say a few things about that photo in Tatler. I have no regrets. The article was about the 20 cleverest people in England, covered up only by the thing that makes them clever. A saxophonist, for example, had only his saxophone, and an artist, his easel. So I was covered by books."

Despite the photographs, the creation of a compelling biography was an arduous and careful task, one that was anything but glamorous. "I put a little article in every local paper," she recalls, "asking anyone with any relation to Georgiana to get in touch with me. I had to pass my drivers test, and then drove all around England visiting people's homes. Many people were basically bewildered, but would invite me in and leave me alone with a box full of letters. I would read through them and try to fit the pieces together.

"I re-wrote this book three times," Foreman says. "But I was not changing the plot, it was more like revealing the story which was already there, the story of Georgiana's journey toward self-actualization. At the same time, I had to keep readers turning pages. In order to keep the plot moving along, I had to withhold information. At the end of the first chapter, for example, I tell readers about the birth of the Duke's illegitimate child. I could have revealed that information anywhere, but finding out about Georgiana's husband's illegitimate child on Georgiana's wedding day creates the most dramatic experience for readers."

Foreman's new nonfiction project is similarly dramatic. "Oh -- I'm so excited about it," she says, "It's called My American Cousins, and it's about these Brits who thought the Civil War sounded so interesting that they decided to come over and fight in it. There are five main characters in the book, though there were hundreds who came over."

The success of Georgiana has brought Foreman astonishing publicity for a biographer, but Foreman is no stranger to celebrity. Her late father, the screenwriter Carl Foreman (High Noon, The Bridge on the River Kwai, The Guns of Navarone) was blacklisted during the McCarthy period when he refused to "name names" during the Communist witch-hunt. He fled to England, where Amanda was born in 1968. "We moved around so much when I was young," says Foreman. "I was very shy, so shy that I would walk across the street if I saw someone I knew rather than deal with talking to them. I suppose I saw in Georgiana the best friend I never had. She was so comfortable with herself, and being in the public eye, and I guess I wished I could be like that." ![]()

Amanda Foreman will be at BookPeople on Tuesday, Feb. 6 at 7pm.