Austin Yards Where Weird Finds a Home

Seven front lawns that push beyond garden gnomes

By Caroline Drew, Fri., May 2, 2025

Come, walk out into the yard with me. Sure, your yard. Stand at a good surveying distance and assume the stance: hands on hips or clasped behind your back, eyes comically squinting or stretched open. Take a look around. Is something missing? There, next to the cactus threatening to take over the left corner, wouldn’t a pastel pink dinosaur complement the blooms? Or perhaps a rusting chandelier would hang nicely from a lower branch of your cedar tree.

We’re already outside, so let’s go for a stroll. It won’t be long before we spot metal creatures or a bottle tree. Walk a little farther and undoubtedly we’ll stumble upon a more elaborate display. If one isn’t immediately evident, peer a little closer; it may be poking over a fence in a backyard.

The front yard is an in-between zone, a meeting of public and private. Though undoubtedly private land, front yards and porches are endlessly on display. Some spectacles are unintentional – a lawn littered with Razor scooters and basketballs tells the story of a busy family and active youngsters; neatly trimmed hedges and blossoming flowers evoke a master gardener with time and dirt on their hands. Yard signs, flags, and door decor speak more directly to passersby, illustrating values and belief systems, team allegiances and feelings – usually negative – toward solicitors. Art yards call for a closer read.

An art yard springs forth in a slow creep, often beginning with a singular object. You know an art yard when you see one: a curated display, sometimes crafted, sometimes assembled, sometimes thematic, sometimes eclectic, but undoubtedly intentionally arranged. Often they have materials in common: human and animal figurines, bowling balls, wooden skis, scrap metal. The foundation of an art yard is typically found on the side of the road, furnished with thrift store treasures, and accessorized with gifts.

Don’t mistake this summary for a guide or a definition. Art yards do not come with a manual, nor an explanation. Rationale and interpretation skirt the edges of an art yard. Arguably, they miss the point of the entire endeavor.

Folks across the city have long used their yards and homes to sculpt, collect, and exhibit artistic creations of all kinds. Art yards are hardly phenomena unique to Austin – the SPACES Archive maintains a map and catalog of art environments across the globe. Still, it’s undeniable to the slightly-more-than-casual viewer that Austin is home to an astounding number of personalized lawns and art environments. We’re a city that fights to maintain weirdness in every HOA and tax code. You’re never too far from something unique if you’re willing to see it.

The yards I visited, presented here, represent a fraction of those in Austin. Their creators draw from their interests, their lived experiences, their restlessness, their communities, and their values just as we all do, and their expression can’t help but spill out into their living space. Their manifestations, many of which have taken shape over decades, are monuments to the idea of old Austin, entangled with the Hill Country flora and its iconography and industry. They are also as ephemeral as nature is, as a city is, as property taxes are. We certainly can’t all step out into a yard, much less one we own, but we can all find something to appreciate in those who have made their spaces theirs.

Violence and Decay Become Playful Display:

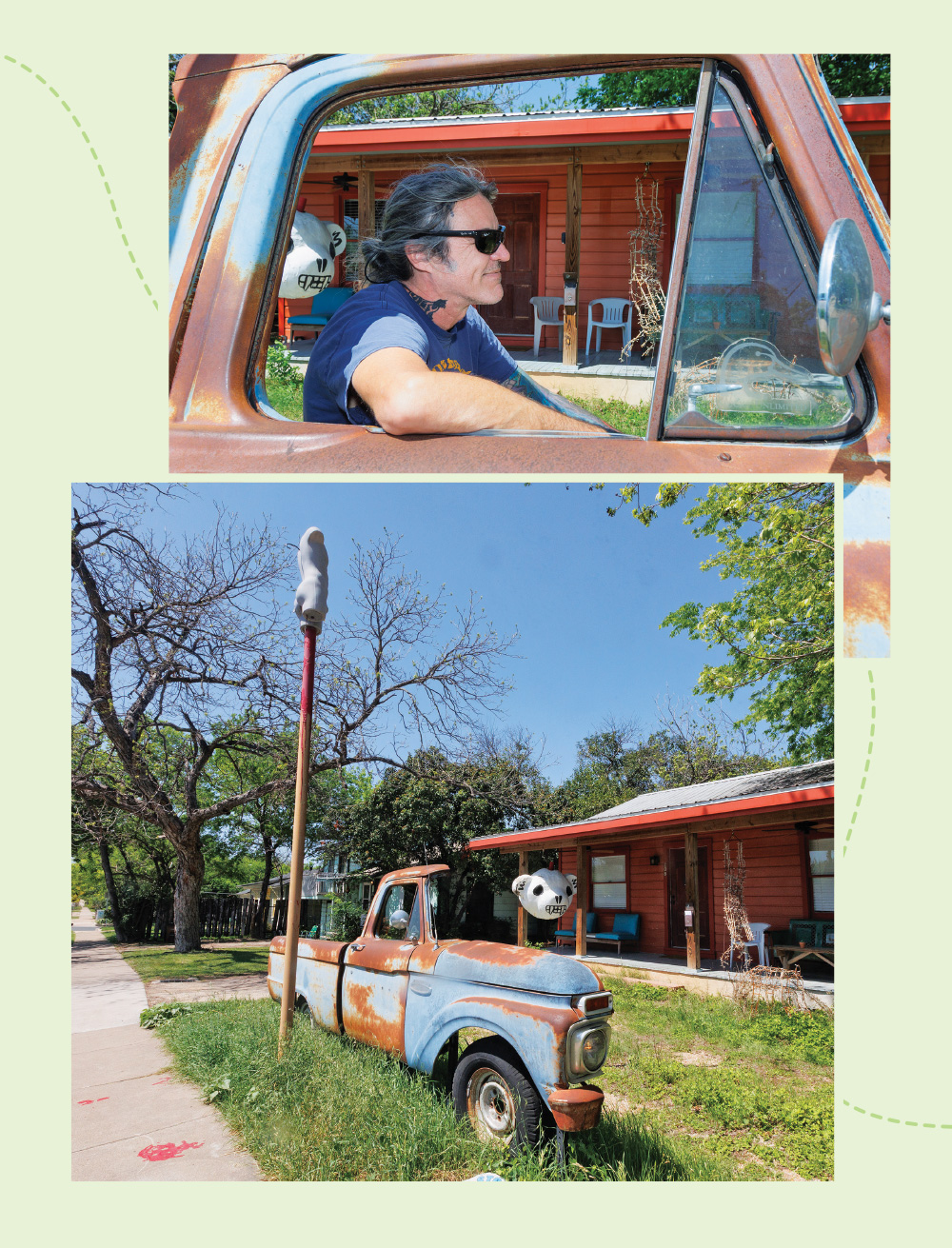

Jim Mansour’s Slice of Bluetiful

Jim Mansour’s display was the first I saw when I moved to Austin. His current diorama, or the bulk of it anyway, was born of a single moment. Standing dizzily outside of his 1965 Ford F100 in 2018, Mansour had just been T-boned. In a matter of seconds, he had gone from a straightforward drive to a metal-encased somersault. When he stepped out of the car and regained his balance, he saw that the passenger side was untouched. He knew exactly what to do.

“It took me six years to get it figured out and put it in the yard,” says Mansour, grinning. “But I knew right away that I would.”

Slice of Bluetiful, Mansour’s punny name for his automotive sculpture, stands proudly in front of his home on North Loop. Perhaps not everyone would’ve glimpsed the opportunity to create a lasting work of art in a shocking accident, but Mansour’s eye has long been attuned to art yard potential.

“My first yard art project was a big dart,” he says. On a drive to Marfa, Mansour spotted steel arrows and sought out an inexpensive method of making his own. “I took PVC and cement and I made one,” he says.

As projects deteriorate in the elements, Mansour configures new displays, letting the moment inspire his next move. North Loop neighbors may have spotted the teddy bear skull – a devolved project – on his porch, or may remember a more brutal object on display in 2012.

“I had a 12-foot fully functioning guillotine out front for a year and a half,” Mansour says, laughing. The police eventually had their way with it, but Slice of Bluetiful promises to stand proudly in the yard for as long as possible, with further adornments on the way.

“I do like attention and I do like answering questions about art. So it seems like there will always be something, but I don’t have a plan,” Mansour says. “I do just love having something out front there, especially that truck.”

Salvaged Finds in Concert With Plastic Minds:

Scott Stevens’ Smut Putt Heaven

Mansour’s yard got me looking for art yards, which seemed to pop up left and right all around Austin. Eventually, I stumbled upon a Yard Art Tour which Scott Stevens had helped to orchestrate from 2010-2012. Stevens included his own yard, dubbed Smut Putt Heaven, on the tour. I stopped by to take in his creation and learn more.

Smut Putt Heaven began as a combination of Stevens’ interests: a long-held desire to build a cactus garden, and an enduring love of Alice Cooper. He first perched 15 doll heads on sticks, one painted in the rock star’s style of makeup. The date was May 28, 1995 – the 20th anniversary of Stevens’ first Alice Cooper concert. Though he didn’t realize that at the time, looking back on it later it seems pivotal to his yard’s journey. Piece by piece, he added plants and scavenged material, building structures and sculptures beyond his original imagination.

“It’s not something that’s easy to predict,” Stevens explains in his mild-mannered tone. “It’s not like I have a master plan, it’s more like an impromptu jam that keeps going and going.”

The extemporaneous, hands-on effort of shaping yard creations is therapeutic for Stevens. Difficult times find him tinkering in his yard, where his original sources of inspiration spring eternal. The six cacti cuttings he planted in the late Nineties are now sprawling cactus castles climbing around his metal creations. Using wire and concrete, Stevens erected a long-lasting monument to Cooper in 2014: a freestanding sculpture of his eye, adorned, of course, with his trademark makeup. It stands parallel to a green, all-seeing eye created in the same fashion, reminiscent of Stevens’ surrealist cartoon-style paintings. The two serve as watchful guardians of the artist’s garden.

A musician himself – he played bass in the Butthole Surfers during their Seventies days in San Antonio – Stevens has shown Cooper’s children the art their father inspired him to make.

“They get it,” he says, smiling. “They think it’s cool.”

Educator’s Self-Molded Monuments Stand Confident:

Ira Poole’s Creative History Lesson

Ira Poole speaks of his yard – named Best of Austin in 1992 – in a similar tone, though his and Stevens’ yards could not look more different. A lifelong educator, Poole has brought his dynamic, hands-on education style to AISD classrooms, the marching band, and a robust 4-H program.

“I call myself an educator, not a teacher,” he explains, because he seeks to help people learn to teach themselves. His yard display is part of this goal.

Driving by his home on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in the Rogers Washington Holy Cross historic Black district – a house Poole helped build – the Statue of Liberty replica is probably what catches your eye first. At her feet sits a map of the United States and Mexico. It’s an apt place for what Poole sees as a celebration of the Constitution and the ideals of liberty and free speech.

Concrete is Poole’s medium of choice, poured into custom molds he paid for by selling extra castings. Across the yard from Lady Liberty, a sphinx lays painted in red, white, and blue, perched on a map of Texas and surrounded by a colorful, patchwork rock garden inspired by Poole’s grandmother’s quilts.

Poole had intended to use his first yard decorations in the classroom, or perhaps have them displayed in the schoolyard. When the administration denied that request, he began turning his yard into its own classroom. Twenty minutes outside of town, Poole owns and maintains a ranch that long served as a classroom as well. On field trips, he taught the students to plant and harvest, feed the horses and cattle, and identify native plants and insects.

I get a taste of these trips from an interview with Town & Country that Poole included in a “time capsule” he shares with me – a DVD tape of moments from his life he’s proud of, stitched together with quotes and maxims. Many of the clips focus on Poole’s yard art, including local news coverage from 1987, celebrating the Constitution’s 200th birthday. The coverage shows a young Poole in a crisp khaki shirt and matching shorts telling the story of his yard with a gleam in his eye that still lights up his face today.

The capsule also features shots of Poole, always adorned in patterned shirts, cowboy hat, and bolo tie, on the ranch and around town on his beloved palomino horse, Playboy.

See What Can Be Under the Sea:

Lois Goodman’s Mermaid Oasis

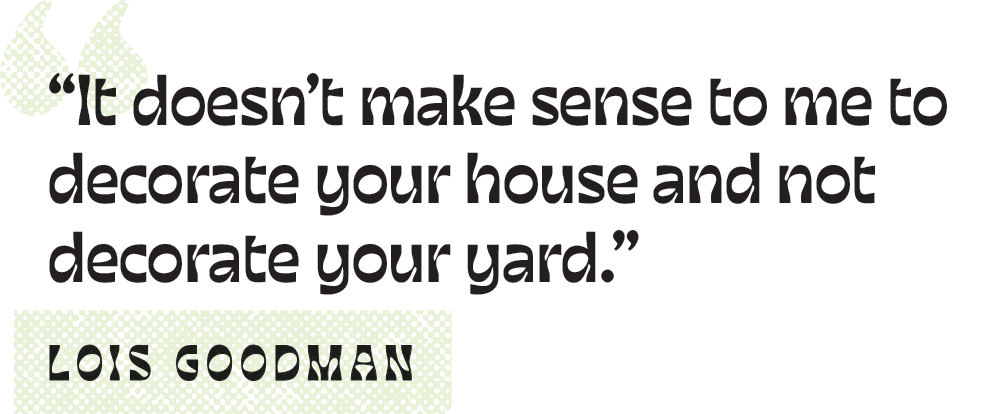

Like Poole, Lois Goodman has a sense of flair and style that transcends her yard.

“It doesn’t make sense to me to decorate your house and not decorate your yard,” she says.

A longtime art car driver, Goodman finds opportunities for self-expression in everything she touches, from clothes to cabinets. When she bought her house in 1993, the backyard fence was in need of replacement. Never a fan of adhering to tradition, Goodman told the builders she’d hired: “Just cut it, the top of it, in any way.”

The shape they left ebbed and flowed like a wave, with one sharp angle that simply begged to become a shark tail. Shark tail it became, and the rest of the fence followed suit, becoming a tableau of underwater scenes complete with mermaids and a corner rendition of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus.

In time, the underwater theme trickled from the back fence through the front yard. A kaleidoscope driveway leads the way to Goodman’s lime-, lilac-, and turquoise-colored house. Alongside the driveway runs the Rock Star Rock Garden, featuring Janis Joplin, David Bowie, and Bob Marley, to name a few. Brightly painted aquatic animals, shells, and ceramic objects are grouped in loose themes throughout the front yard.

On the gate to her backyard is a mosaic mermaid Goodman is particularly proud of.

“Everybody says it’s a mermaid theme, but really I’m just more comfortable in the water than I am on land. It’s always been that way,” she says.

Her trust in her intuition not only informs her work as an intuitive consultant – a guide somewhere between therapist and life coach who helps clients tap into their inner wisdom – but her artistic work as well. Arranging objects she’s collected in her home or in her yard, she feels that she simply knows where things belong and can trust her senses to design a space. Her intuition has led her through a detailed customization of her home, where each tile, knob, and doorpull add to the bigger picture of her vision.

“I can see what can be,” Goodman states.

Though she still struggles to call herself an artist – “It’s an emotional issue for me,” she says – Goodman spends her life turning the world around her into art and finding ways to share her colorful perspective with others.

Collected Ceramics and Artifacts:

Sharon Smith’s Smithsonian

Goodman’s friend Sharon Smith is an undeniable collector and artist. A lifelong teacher, ceramicist, and sculptor, Smith bought her North Austin home in 1991 and set about transforming every inch of her property into her own Smithsonian, if you will.

“I have neolithic pots, I have 400-year-old things, I have a piece of Tibetan fresco that weighs 1,000 pounds,” Smith says, gesturing around her packed home. She moves aside several other artworks so I can get a better look at the fresco.

The surfaces and walls of Smith’s home, inside and out, are each a mini-installation, a three-dimensional collage of cultural objects and artisan works. Her delicately crafted arrangements tie together ancient artifacts with brightly colored plastic figures in a seamless amalgamation of human creation across time and space. In her yard, salvaged finds and artistic creations find equal footing on rows of overturned pots, framed in wheelbarrows or hanging from Smith’s impressive cedar tree.

“I love rust and I love old [things],” she says.

Antique irons, broken rotating locks, and forgotten carousel horses all have a home in her yard. Smith’s friends and former students appreciate her collector’s eye: their pre-used treasures and multidisciplinary creations – ceramic dog angels, delicately painted shadow boxes, and stained glass – are on display across the property.

“Everything here is an accident,” Smith says, smiling slyly. “And everything out here reminds me of someone.”

Smith frets over the future of her collection and acknowledges the toll that unending upkeep in the yard can take. She makes the most of cooler spring weather to primp her yard and take inventory of any creations that might’ve been damaged by storm or wind. Together we weave slowly between tables stacked high with planters and art pieces, brushing aside fallen leaves and pulling weeds from the eclectic garden that grows in and around her yard collection.

“I have to be grateful I’m still out here playing with my plants,” she says.

Charitable Cheer for All Who Gather Near:

Florence Ponziano’s Comfort House

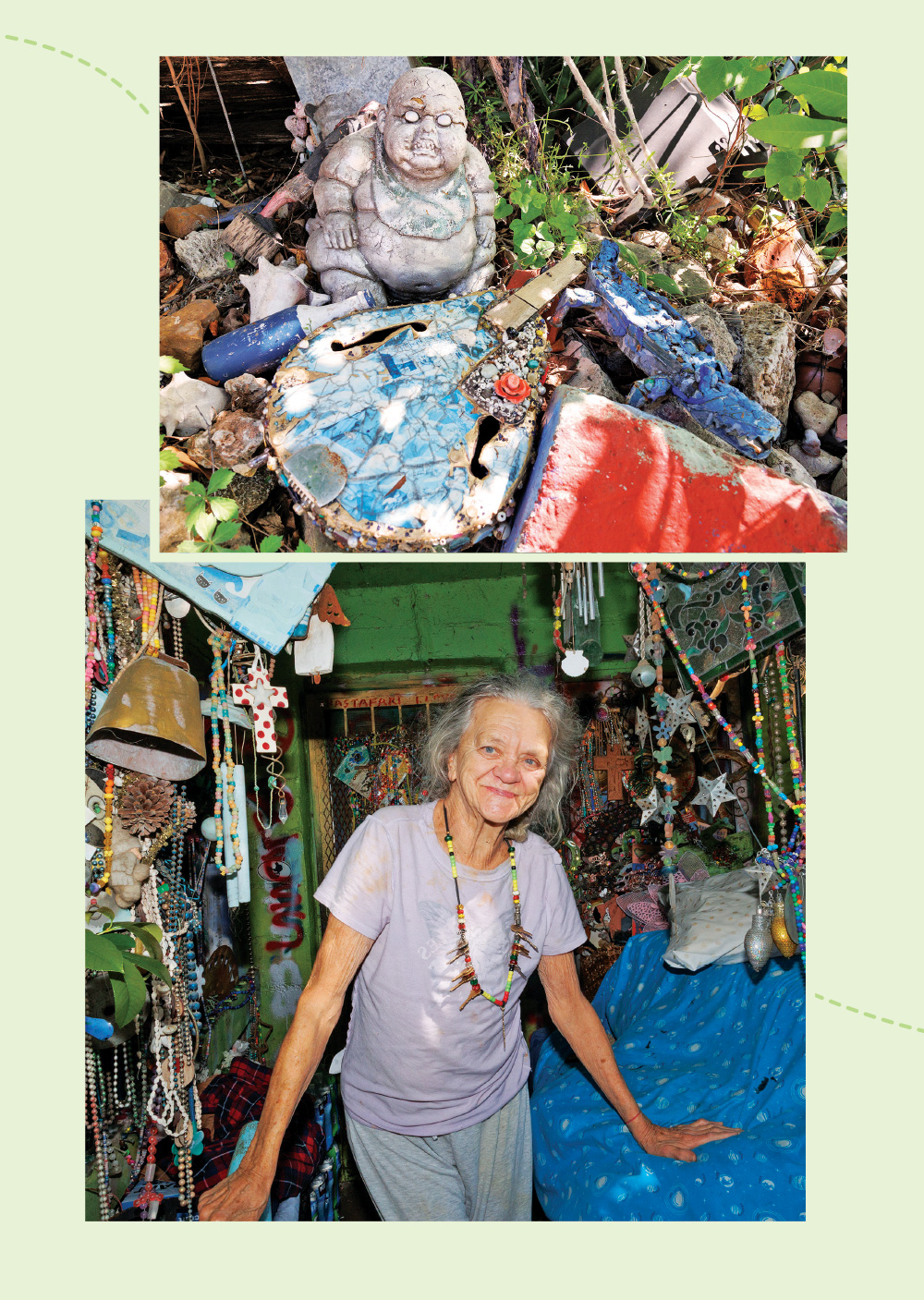

It’s a sentiment Florence Ponziano, a yardist on the other side of town, would likely agree with. Contributing to community and engendering collaboration are at the heart of her work.

Florence’s Comfort House is as full of energy and enthusiasm as Ponziano herself. The octogenarian stays busy caring for Montopolis’ children, cooking for neighbors, and sharing “love and light” with everyone she meets.

“All my friends are retired,” she laughs. “I’m the only one still working. I don’t know where I get the energy.”

Arriving at her Southeast Austin home just after sundown, Ponziano shoos me into a chair and insists on fetching me something to eat: two fried chicken wings and a SunnyD, leftovers from the community meal she’d served an hour earlier. Surrounded by Mardi Gras beads and Cabbage Patch Kids dolls, Ponziano tells me the story of her home.

“We didn’t have money when we moved here, but we found all kinds of things,” she says. “We scavenged and I thought, man, we’re not great artists, but we found more and more things and we put rocks and bright colorful things [in our yard], and the kids loved it.”

She remembers drawing on discarded plywood and then encouraging her neighbors’ children to paint it as brightly as possible.

“I never did art before,” Ponziano says. Yet, as a musician and a believer in the power of creativity, she quickly took to arts and crafts as a way to engage the kids she cares for. Now, in addition to plays and concerts, visual arts projects abound at the Comfort House, a nonprofit Ponziano registered in 1999 that supports her low-income neighbors.

Where Ponziano isn’t storing art or found treasures, she’s storing school supplies and clothing for “her kids” – “I’m related to all the kids now; I’m all their nannies,” she says – and food for a pantry to provide for her neighbors however she can. Drawing on her endless creativity, she turns matching resources to those who need it into an art in and of itself, while insisting on bringing color to every corner.

“I’m an artist – well, I don’t think I’m a real artist, but I love color. I did this for fun,” she says, waving at her yard full of well-fed cats, beloved toys, and cheerful creations. “Because I like color and I don’t like to be in darkness. I need the light around me.”

Though Ponziano may not see herself as an artist, she has no problem creating art and putting it to her use. Her often-giant mosaics – dragons, lizards, a series of ornately decorated guitars – are resold at nonprofit auctions or for the benefit of her own organization.

“What a life I live,” Ponziano beams, with her signature gratitude. “I do fun things and I get to use them to feed my kids and my neighbors.”

Mighty and Tall, a Cathedral to Worship Art for All:

Vince Hannemann’s Cathedral of Junk

When talking about yard art or art environments in Austin, there’s one example that stubbornly rises to the surface of every conversation. I put off talking to Vince Hannemann for a while. The self-appointed Junk King, creator of the South Austin Cathedral of Junk, cuts a towering figure in the Austin art yard scene. His art environment, aptly named by his mother, draws year-round tourists and has been the subject of many articles and documentaries.

Now 36 years in the making, Hannemann’s home started drawing visitors early on. In the years since, it’s become Hannemann’s sole occupation. Visitors are allowed by appointment only, made over the phone. The complications of maintaining a sense of privacy at his residence while exhibiting his backyard work weigh on him. Sometimes, disappointed by theft or vandalism, he dreams of keeping the cathedral to himself.

Then again, “the hardest thing I do is tell people no at the gate,” he tells me.

It worked out for both of us that I waited to visit Hannemann. He took January, February, and March off this year to clean and expand the cathedral. An ADA ramp now snakes neatly to the first story of the cathedral and new pieces have been incorporated.

Visitors far and wide have contributed their own junk – er, creations.

“This Girl Scout troop came one day and they brought me these duct tape roses that they made,” Hannemann says, eyes shining mischievously behind his yellow-tinted glasses. “They presented me with [them] and then they sang me a song.”

Hannemann places donated items, like the roses, as he sees fit. The singularity of his artistic labor is part of the draw of the Cathedral of Junk, as he sees it.

And, of course, “It’s big. The amount of labor involved in it really comes through. This is not a collaborative effort,” Hannemann explains, though he acknowledges that “different streams of luckiness have come together” to make the cathedral possible.

“Nobody helped me mix this cement,” he says. “Everything you see around here I have touched multiple, multiple times.”

Visitors, Hannemann believes, “feel that energy. Then there’s the energy that comes from all the previous lives that these things have lived ... and then [there’s] the energy from people’s memories when they [see the things].”

It is big – big enough to require a building permit. A six-month renovation in 2010 brought the cathedral up to code standards. Sitting in a second-story landing, I can’t help but marvel at the solidity of Hannemann’s structure and the variety of objects contained within.

“One of the biggest lessons I ever learned,” he says, leaning toward me conspiratorially: “You can’t have too many round things. When in doubt, more round things.”

Unexpected Creations for an Uncertain Future

Doubt takes on new forms as these artists age – forms that more round things can’t always assuage.

Painter and yardist Janis Tate maintained a cheerily yellow-themed display near South Congress for years.

“I would see how people would stop and stare,” she says. “Everybody remarked, 'This makes me so happy when I’m on my way to work in the morning.’ And I thought, if just for a second somebody looks at these and sees the silliness of it all and it resets their day, how great is that?”

Sunshine-toned bowling balls still peek out of her yard’s greenery, but Tate’s asthmatic lungs can no longer handle the bowling ball refurbishing method she prefers, an intensive process of sanding, spray painting, and sealing.

Many of Tate’s fellow yardists ponder how their contributions to Austin’s weirdness can continue without them.

“It’s not static,” Hannemann says of the Cathedral of Junk. “You can’t put it under a glass dome.”

He dreams of a perpetual future for his creation, where it continues to be a celebration of eccentricity – as in flux as the city itself.

“I feel like I have a responsibility, or something, to fight the good fight,” Hannemann says.

Smith shares similar concerns. In contemporary Austin, she feels that “weird [has been] eclipsed by wealth.” She worries that Austin’s new demographic doesn’t value art – folk art and historic pieces in particular – as they once did, even if they have more funds to pursue and protect arts in the city.

Ponziano, for her part, plans on never dying. It’s the only way she can see her artistic and charitable work marching forward.

These art yards, ephemeral as they are, have formed over decades, growing and shapeshifting alongside their creators. They have adapted to challenges from nature, building codes, and neighbors so far, maintaining a beacon of Austin’s quirky, creative identity. Though contributing to such a reputation was never an explicit goal for these artists, confronting the future of their work immediately sparks reflection on the way Austin has changed.

“I don’t know Austin anymore,” lifelong resident Tate sighs. “It looks like it’s here, but I don’t know. I don’t know about the appreciation of making and building art.”

Lamenting foreclosures of beloved venues and galleries, mourning the slow crushing of character-rich bungalows, and fretting over the instability of affordable housing for creatives, we may be looking at an Austin where expressive work is dwindling. Who among us is prepared to pick up the impromptu jam, find more round things, and bring color to darkness?

The only way these artists see Austin’s spirit surviving the pruning and smoothing over it has experienced, is through expressive creation. “Make art,” Tate directs, “and don’t try to make perfect art. Just make.”

Looking for more local art yards?

These Austin creators offer further insight.

- Carl McQueary’s Estate Services of Austin keeps art yards of the past and future possible.

- Weird Homes: The People and Places That Keep Austin Strangely Wonderful by David J. Neff and Chelle Neff chronicles the authors’ Weird Homes tour, which the Chronicle covered during its run.

- Public art and outdoor sculptures have found a home in North Austin’s Stephenson Nature Preserve.

- Objects requiring a little more care and explanation are preserved in the Museum of Natural and Artificial Ephemerata.