Shepherding Shepard

The material legacy of playwright Sam Shepard calls Central Texas home

By Adam Roberts, Fri., Dec. 6, 2013

If you turn immediately to your left as you enter "The Writer's Road," the Sam Shepard exhibition on display at Texas State University's Wittliff Collections, you'll come face-to-face with a striking photograph of the Church at Ranchos de Taos. This National Historic Landmark and World Heritage church was built between 1772 and 1816 in New Mexico, the state that Shepard has called home for years. Above the photograph are printed the words "Spirit of Place." Beneath it appears a quote from the famed Texan writer J. Frank Dobie, which reads in part: "I would interpret [the Southwest in my writings] because I love it, because it interests me, talks to me, appeals to my imagination, warms my emotions; also because it seems to me that other people living in the Southwest will lead fuller and richer lives if they become aware of what it holds."

Anyone familiar with the writings of Shepard will recognize immediately the resonance of Dobie's words in the context of the dramatist's playscripts and screenplays, artifacts of which are collected in the holdings of the Wittliff's Southwestern Writers Collection. As you move through the exhibit, the rationale for cataloging Shepard's work in an archive dedicated to this region becomes ever more apparent.

There's the notebook in which Shepard scrawled an early draft of his play Simpatico, opened to a page labeled "Scene One," with "9/3/92, Tenn. Hwy. 40 W." scribbled in the upper right corner. Asked in a 1997 interview for The Paris Review if it was true that he wrote the play in a truck, Shepard replied: "Well, I started it in a truck. ... I've always wanted to find a way to write while I'm on the open road. I wrote on the steering wheel [on Interstate] 40 West, the straightest one. I was going to Los Angeles."

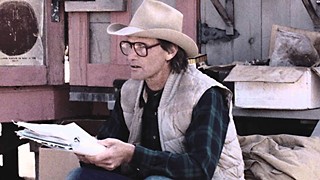

There are the post-production rewrites for Shepard's screenplay Paris, Texas and the mock-up version of his book Motel Chronicles, which features some diary entries written during one of his stints in San Marcos. There are his handwritten directorial notes for Fool for Love, set at a hotel in the Mojave Desert, and the shooting script for Silent Tongue, set on the Llano Estacado. It's this image of the rugged Shepard, returning time and again to the West, that recurs so prominently throughout "The Writer's Road."

The hit exhibition – "It's been one of the most popular exhibitions we've ever staged," says David L. Coleman, director of the Wittliff Collections. "Everyone from school kids to college students to retirees has been coming to see the show." – succeeds in not only establishing Shepard's ties to the region but also bringing to the fore his process as a writer. "The fascinating thing about Shepard's literary papers is that you can literally trace the arc of his creativity, from his earliest raw scribblings in notebooks through his numerous revisions and polishes all the way to the final finished story or play," says Coleman.

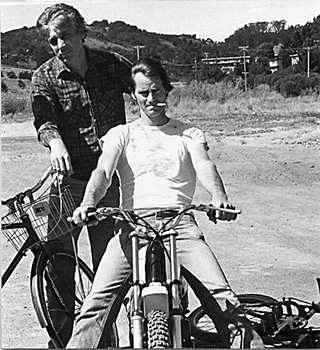

The exhibition's curators realize the importance of providing opportunities that engage visitors actively in its exploration, going so far as to put together an interactive scavenger hunt activity that leads visitors through the narrative of Shepard's life, both personal and professional. (It's fun even for adults.) Of particular recommendation to those "on the hunt" is a section focused on Shepard's relationship with Johnny Dark, a somewhat unlikely friendship chronicled in director Treva Wurmfeld's recent documentary Shepard and Dark. The 2012 film examines the relationship between the two very different men, in large part through the innumerable letters they've written to one another over 40 years. This may sound like a simple heartwarming story of friendship, and at many times it is just that. But the film does not always make for easy watching. Themes of abandonment pervade, and the documentary makes no attempt to sugarcoat the true story, told primarily through interviews with Shepard and Dark themselves.

A visit to "The Writers Road" makes clear the rich holdings of the Shepard collection at Texas State University. And yet the Wittliff is not the only repository for Shepard's materials in Central Texas. In fact, the other major collection of the dramatist's work exists just over 30 miles to the north, at the University of Texas' Harry Ransom Center. According to HRC Assistant Director for Acquisitions and Administration Megan Barnard, anyone interested in how Shepard developed his work will find ample material for study in the Ransom Center's holdings: "The [HRC] collection is filled with drafts and revisions of many of Shepard's plays, stories, poems, and other works. Especially interesting is a series of notebooks in which Shepard recorded thoughts and ideas related to his plays, acting roles, songs, and travels. These notebooks offer a unique glimpse into Shepard's creative work not just as a writer but also as an actor and musician."

In fact, 2013 might be called "The Year of Shepard" in Central Texas. Not only are Shepard's materials on view at the Wittliff and available for study via the Ransom Center, but a book focusing on the correspondence between Shepard and Dark has just been released by UT Press. Two Prospectors: The Letters of Sam Shepard and Johnny Dark, produced through the Wittliff literary series, draws from Texas State's Shepard archive and was edited by faculty member Chad Hammett. Coleman believes the volume "may be the closest thing to a memoir Shepard ever publishes."

As it turns out, letters play an important role throughout Shepard's life and work. Although I had always been familiar with Shepard, my own artistic interest in his work was heightened recently in the form of one of his least-known pieces: Tongues, a short poem-play for a sole speaker and set to percussion that Shepard composed with actor/director Joseph Chaikin. (A handwritten letter from Chaikin to Shepard is on display in "The Writer's Road.") Earlier this year, in a nod to Shepard's most surreal of leanings, I chose to stage Tongues in an outdoor swimming pool for the Austin Jewish Repertory Theater, where I am artistic director. While working through the script both alone and with the performers, the importance of letters to Shepard became overwhelmingly evident, so much so that we crafted the production's playbill in the form of a letter, folded and placed inside an envelope, which each patron was handed upon entry.

Until I directed Tongues, I had no idea that letters were such a motif – make that near obsession – for Shepard. Visiting the Wittliff exhibit and watching Shepard and Dark made that realization all the more palpable. But why letters? A clue might lie in an answer given by Shepard in an interview last year for GQ: "I don't have a computer. I don't have an Internet, I don't have the e-mail, I don't have any of that shit."

The cowboy poet has little use for technology, I wager. That image of Shepard driving down 40 West in a beat-up pickup, preferring the open road to the open skies as a means of travel, seems such a perfect complement for a constant letter writer. There's something about the experience of physical reality – whether it's a letter in the palm of the hand or the passing air of Highway 40 against your cheek. To experience Shepard's artifacts in their scribbled, scrawled, and beat-up condition is to feel the presence of the cowboy's hand behind them.

As I came full-circle to the "Spirit of Place" wall hanging at the end of my visit to "The Writer's Road" and re-read Dobie's quote, I was suddenly reminded of a line from Tongues:

"SPEAKER (voice to a Blind One):

"In front of you is a window ... In the window, in the glass, is your reflection ... On the wall are pictures from your past. One is a photograph. You as a boy. You standing in front of a cactus. You're wearing a red plaid shirt."

That's Sam Shepard, reflected in the windows – and writings – of the Southwest.

"The Writer's Road" is on display through Feb. 14 at the Wittliff Collections, on the seventh floor of the Albert B. Alkek Library, Texas State University-San Marcos campus. For more information, call 512/245-2313 or visit www.thewittliffcollections.txstate.edu.