Not Too Tight at All

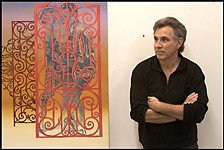

The disciplined abstracts of Helmut Barnett

By Wayne Alan Brenner, Fri., Feb. 5, 2010

There's an explosion of color inside the big white 100-year-old house one block east of I-35 on Third Street. The house is the studio of Helmut Barnett, artist of large abstract paintings, of smaller abstract drawings. The explosion of color is his many works rendered on stretched canvas and fine thick paper: posed on easels, stacked in corners, hung on walls, piled upon tables, stashed in drawer after drawer of several wooden cabinets.

He's a busy man, this Barnett. He's currently preparing work for his fourth one-man show – appropriately titled "Big Paintings, Little Drawings" – at Wally Workman Gallery, and he has a warehouse worth of brilliance after almost four decades of pursuing his art.

"I've been in Austin a long time," says Barnett, "and I've been very lucky with studios. I had a studio on Congress Avenue for 28 years. That was 908 Congress, the same block that Little City is in now, and I was there from '74 to 2002. And before that I had a place on Sixth Street, upstairs from where the parkside restaurant is now."

Barnett's personal history is captured on the tall refurbished walls of the former residence that he's occupied for eight years now, cherished images marking the passage of time, framed among a spectacular array of paintings and drawings: photos of the band he played guitar with as a young man in Germany, of the plane he flew in as a radar technician for the United States Air Force, of his old studio on Congress, of Barnett and his wife on a date in the restaurant – the Avenue – below that old studio, of the couple's daughter, who's now attending Texas A&M.

History, arranged upon the verticals like the diversity of shapes in Barnett's biggest works. History, but nothing near the current studio's own century mark, right? Even though there has to be a substantial number of years to account for the skills the man has acquired, the finesse with which he brings his polychrome wonders into being.

"I'm going to be 64," says the artist, running a hand back through the thick brush of gray hair atop his head. "I don't feel 64."

Barnett uses whatever's necessary (but mostly acrylic paint) to translate his visions from internal to external, and the results are often stunning. Not in abstracts like abstract expressionism's more emo slashes and splotches that pretty much assault a defenseless surface, but strategically applied, complexly balanced abstracts. Like Mies van der Rohe tweaking the color schemes of lepidoptera. Like Joan Miró and Piet Mondrian collaborating at the peak of a Ritalin binge. Like no one does quite the way Helmut Barnett does.

"I like to draw a lot," says Barnett, gesturing toward a small outcropping of sketchbooks on one table. "I like black-and-white drawings, pencil drawings. The drawing is very spontaneous and quick, and there's a bit of playfulness involved – sometimes I'll start drawing with my left hand, just to get different shapes. And I do put some recognizable things in the abstracts, if they show up. But I don't intend to; I don't know what they're going to look like beforehand. This painting here, for instance, this shape started out as just a black blob, and I made it look more like a bust. It's called Bad Boy Bust." He chuckles. "I like alliteration in some of my titles.

"So, yes, sometimes I do work the shapes out: I see something I like, and I develop it a bit, kind of refine it. And usually the drawings stay the same size; but, lately, what I've been doing for my paintings ... I'll make little sketches – I have books that I fill with drawings – and when I do one that I like, I go out here and put on my overhead projector and project the image onto a canvas. And that way it comes out much larger but with exact proportions. And I'll paint it that way. This," he says, walking over to an unfinished piece on an easel, "is one I'm working on now, for the new show."

So amazing, the subtle gradations of color, that it has to be asked: He doesn't use an airbrush, does he?

"No, I don't," says Barnett. "I tried an airbrush, years ago, but I didn't like it. I found it ... too mechanical. This is just done very carefully – with a lot of taping. I use a lot of masking tape, and I do a lot of layering with a brush and just blend the colors together. I use a large brush, and I work very fast. I have to, because the paint dries so fast. It's acrylics – it's not oils. Large areas are really hard to do."

And yet look at how one color smooths into the next; see the barely discernible strokes of sable or camel hair or whatever pulled the pigment. Never mind, even, the overall visual impact; just, ah, groove on the skill of application. It's so wonderfully ... controlled.

"Well, you could look at it like that," says Barnett, smiling, seeming a shade uncomfortable with the compliments. "You could look at it like that – in a positive way. Or you could look at it in a negative way." He shrugs. "Maybe it's too tight."

As if providing evidence of his efforts in combating such putative tightness, Barnett points to another work on the other side of the room. "That's some of the masking tape I used," he says. "I cut it into pieces and glued it on there, just kind of messed around with it." Look: Short lines of textured color form a staggered spectrum in many rows across a large rectangle. Beautiful. And slightly reminiscent of something Lance Letscher might create.

"Ah," says Barnett, "I know Lance. What I do that's more like what Lance does, I paint on the collages I make. I take books – physics books, chemistry books, mechanical drawing books – because I like the little shapes in there – and I play with the shapes that are in there, cut them up, extend them into drawings, and paint over them. I make the collages at home: That's where I glue them together. My wife doesn't like me using the dining-room table, but that's where I do it. And then I bring them here for painting."

And over here, on a pair of paintings halfway up one of the walls, what technique produced the strangely modulated gray tones in the background?

"That's a solvent transfer," explains Barnett. "What I do, I take pages from magazines and put them in a cookie tray that's filled with lacquer thinner. The lacquer thinner loosens the ink, and if you pick the page up – real quick – and put it on here, then it transfers, and sometimes – see? – you can even pick up a pattern. And I like working in black and white, but most of the things I sell, well, people like color. And so here, on top of the transfers, I did a whole series on what, for lack of a better term, I call ribbons."

And over there is another series, based on other notebook sketches. And over there are variations on red waveforms. And over there are what appear to be giant silhouettes of complex beadwork. And over there is – holy Yves Tanguy, is this amount of work what it takes to make a living as a painter? What about when Barnett was first starting out, after the USAF, after graduating from UT with a bachelor's of fine arts back in '74?

"In the very beginning, I wasn't making a living from my art." he says. "I had to take part-time jobs. But I wasn't married then, and I didn't want to take a full-time job, because I felt – and I felt real strong about this – I didn't want to get comfortable with a regular paycheck and slowly delegate my painting to weekends. And, being single, I was able to go ahead and just take care of myself; I really didn't need a lot of money. So, because of the good graces of my landlord, I was able to work. Plus, I had a friend in the restaurant below; I would work in the original Waterloo [Ice House], get a free lunch and a little extra money. So I got by. And these days ... well, it's still not easy."

Barnett looks around the spacious studio, at the high ceiling that had to be rescued (with a car jack and several 2-by-8s) from sagging, at the formerly graffiti-covered walls now showing white between the dozens and dozens of paintings and drawings and collages and framed photos, at a growing body of work that another artist might sacrifice his left arm to have created. "I mean," he says, a wry smile collaging itself into the contours of his face, "I can come here and make art all day long, but I can't make anybody buy it."

Many people, however, do. And you can, too, of course; or, at least, you can see the newest works – an orchestrated explosion of color and form and techniques – on display at Wally Workman Gallery throughout the month of February at this particular point in history.

"Helmut Barnett: Big Paintings, Little Drawings" is on display Feb. 4-27 at Wally Workman Gallery, 1202 W. Sixth. For more information, call 472-7428 or visit www.wallyworkman.com.