The Iron Man

Longtime stage phenom Ken Webster has a record to rival that of a Baseball Hall of Famer

By Robert Faires, Fri., April 13, 2007

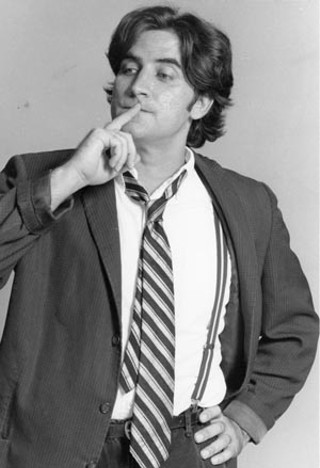

The lights come up, and there he is, like a batter at the plate, alone. For some, this would be a nerve-wracking proposition, like staring down a 99 mph fastball, but not this guy. This guy has been here before – many, many times – and even if you didn't already know that for a fact, you could tell it from the confidence he exudes, the steadiness, the stillness. He knows what he's doing, all right. This guy is in complete control. If he were holding a bat right now and facing Clemens, say, or Oswalt or, just to be nostalgic, Mike Cuellar, he could totally call his shot.

That's Ken Webster, who's once again flying solo on the stage of Hyde Park Theatre, where he's been artistic director for six seasons now but mounting plays for more than 20. Webster in a one-man show is hardly news, even if the one he's doing this time – Thom Pain (based on nothing), by Brooklyn playwright Will Eno – was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2005; this will be Webster's fourth one-man play, and considering that he's revived the other three at least one time each, you can argue that it's more like his ninth or 10th solo show. Even so, it's an occasion, as it has been every time he's performed Eric Bogosian's Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll and Daniel MacIvor's House and Conor MacPherson's St. Nicholas, as it is whenever a skilled player of many seasons, a player of quality, steps up to the plate.

That's what we have in Ken Webster. He's logged almost 30 seasons straight on the local theatre scene, appearing in at least 50 productions as an actor and directing more like 60 shows. Add to that 15 nominations for Austin Critics Table Awards and 42 nominations for B. Iden Payne Awards, and the numbers start to sound like stats on the back of a baseball card, the stats of a player headed for Cooperstown, if not already there. As it turns out, Webster is a bona fide Hall of Famer, having been inducted into the Austin Arts Hall of Fame last year. But unlike most players who receive that kind of lifetime-achievement honor, Webster hasn't retired. He's still in the game and playing harder than ever. This season alone, he's already done one one-man show himself and directed another one for Zell Miller III (My Child, My Child, My Alien Child), he opens his second one this week and is on line to direct the Austin premiere of Martin McDonagh's The Pillowman as soon as Thom Pain comes down. That's a more furious pace than he kept up as a young turk in the early Eighties cranking out productions of unknown writers named Mamet and Shepard and Durang. And as is apparent from his recent work – his slyly hypnotic storytelling in St. Nicholas, the crisp staging of My Child, My Child, My Alien Child – this "Iron Man" is in shape to keep his astounding streak alive for several seasons to come.

The Natural

Of course, as is often the case in situations like this, the streak was never planned. In fact, if he'd stuck to the script life had worked out for him, Webster wouldn't be in theatre at all, much less Austin. While a student at the University of Houston, the Port Arthur native panicked at the prospect of being unable to make a living from the stage and abandoned the theatre department for Radio-Television-Film. From that point, he had lined up a post-collegiate position at a radio station just on the other side of the Sabine River, which means that, instead of this story, we well might have had the Baton Rouge Advocate running a feature on his 30th anniversary as the drive-time jock for WJBO.

But as has happened so many times in the history of man, there was a woman. And she was in Austin. So Webster gave up Louisiana and gainful employment at the mic for romance. Only once he made it here, Webster never actually wound up dating that young lady, so he had some free time on his hands. And that eventually led him to theatre. About a year after landing here, Webster's interest was piqued by an audition notice for a production of Peter Barnes' satire The Ruling Class to be staged at Symphony Square. Despite the fact that the production team was made up of some of Austin's theatre elite at the time and Webster was just a twentysomething from the Bayou City with no credits, he was cast alongside Ed Neal of Texas Chain Saw Massacre fame and John Hawkes, who has since gone on to a fine career in Hollywood (Deadwood, The Perfect Storm, Me and You and Everyone We Know).

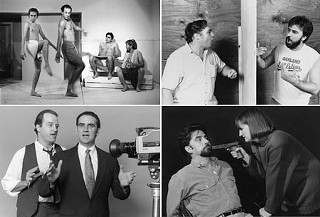

And that was all it took. From there, he jumped into a small role in One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest directed by Bil Pfuderer, which led to parts in a handful of musicals staged by the late director, which led to Webster deciding just to up and start producing shows himself at Fifth Street Playhouse, a tight little 54-seat storefront just west of Congress (what's now the Apple Bar) that makes his current theatre in Hyde Park feel like the Paramount. Under the name the John Bateman Players – a tip of the orange cap to Webster's beloved Astros and their hulking catcher (1963-68) – Webster mounted productions of Bruce Jay Friedman's Steambath and Peter Nichols' A Day in the Death of Joe Egg, and when he couldn't find someone to direct Jules Feiffer's Little Murders, well, he just staged it himself. (Making that production yet more memorable, by the way, was Webster's casting of a teenage Mary-Louise Parker.)

It was the most natural of moves, actually. Webster was one of those kids who discovered the allure of the footlights early on and started staging plays in his garage. In his case, they were based on the then-popular gothic soap opera Dark Shadows and could be seen for the bargain price of one penny. "And when neighborhood kids showed up without the penny, he would say briskly, 'Go back; ask your mom for one,'" according to actress and writer Katherine Catmull, Webster's partner in theatre and in life for 23 years now. "Not just a born actor/director but a born producer! Keeping a tight rein on those comps!" Small wonder, then, that he was able in 1985 to put together a production of Harold Pinter's The Homecoming with $600 borrowed from a local restaurateur.

But that's Ken Webster. He does what he wants, and he always finds a way. When he finds a script he likes, he produces it, even if it seems to have no commercial prospects and is by someone that no one's ever heard of. (Daniel MacIvor? Who the hell's that? Anne-Marie Healey? Melanie Marnich? Will Eno?) When he needs actors who aren't afraid of offbeat, edgy scripts, he seeks them out, leading to casts packed with gifted, fearless performers. And if he wants to pay them for their work – and he has always wanted to pay them for their work – he does, no matter how small a budget he's working with (and even in '85, 600 simoleons was chump change for staging a play). When Webster started producing, the only place in Austin that was paying actors was Project InterAct, the children's theatre company at the Zachary Scott Theatre Center (a company that, believe it or not, Webster was a member of for a few seasons in the mid-Eighties). He led the way among independent companies in compensating actors, and that stands alongside his achievements as an actor and director as his legacy to local theatre.

The Coach

Webster takes care of his players because he is one of them. He knows firsthand what it's like to step into that spotlight and make something made-up feel real. He knows the effort that's involved, the commitment that's required, and the paltry recompense that is the usual actor's lot, especially in Austin. (Eleven people in the house! Yeah!) For the folks who are willing to devote themselves to a show with him, he holds a deep respect, and he makes it his job to pay close attention to them and forge out of their efforts the tightest performances he can.

"Ken is my favorite director in town for many reasons," says Andrea Skola, who's worked with Webster as an actress and currently serves as Hyde Park Theatre's technical director. "One of them is his ability to create a rehearsal environment that produces an amazingly tight-knit ensemble. And I love that, as a director, he has a reason for every movement an actor makes on stage. Every step, look, or glance. The diction and timing of the lines are key. He pays close attention to pacing. It's not that I think these things set Ken apart from the rest – these are important elements for many directors – but the consistency with which Ken implements them is incredible. He's as specific with his actors as he is when he is on stage himself, which makes him a captivating actor to watch, as well."

Kathy Catmull met Webster back in 1984, when he was staging Mamet's Sexual Perversity in Chicago for the first time, and she auditioned for him with her roommate at the time, Bill Friedman. Webster cast them both, thinking they were lovers, which they weren't. Besides setting the stage for her and Webster to become a couple, the experience brought Catmull to a new understanding of acting. "Ken basically taught me how to act. I tend to be too small and filmic, and he would coax me along to share myself with the audience more – a great thing to learn. He also teaches me loads every time about the power of stillness on stage. And of not making faces. When he catches actors making faces, he says, 'Forget your face! Leave it alone! Put every single thing you want to say into your eyes, and your face will know what to do.' Which is really great advice.

"And he has an exquisite ear, maybe the best ear I've ever met. I mean, he understands the music of language really well, and the music of ... feeling, for want of a better word. That is why he is virtually peerless at spotting acting talent, I think. He can hear, immediately, whether a performer is 'acting' or accessing something genuine – that's so precious in acting, the ability to access something real. Those are the only moments on stage that justify the existence of theatre at all, really. But it's astonishing to me how many directors can't tell lousy acting from good – it's like being a tone-deaf choirmaster; it's criminal. But Ken has perfect pitch for acting truth and for language. He drives some actors crazy because he does loads of table work before he puts a show on its feet, and it's mostly just reading scenes over and over, with some brief conversation of discussion, and then reading again. Just hearing a text opens it up to Ken. That sensitivity to the musical arc of a text, and his own ability to access what's real inside him, is also what makes him such a joy to watch as an actor, of course."

Webster will tell you himself that attention to text is paramount to him. He won't get to blocking "the first two, sometimes three weeks of rehearsals," he says, so as to break down the text – marking out beats, underlining phrases, circling key words – and get that music of language that Catmull refers to flowing from the actors' mouths. But the repetition, repetition, repetition is not just for the benefit of the actor, allowing him or her to discover the rhythms in the language and which words are crucial; it also provides Webster as director with the way he can serve each performer. See, actors come at their art from all different directions, employing different methods to achieve results and speaking about it in more languages than you'll hear at the UN. Webster learned over time that you can't direct every actor the same way, so he listens for cues that tell him what direction an actor is coming from. "The table work teaches you how to get the best work with that actor," he says.

It's an approach that's improved his work, he insists. "I'm a much better director now than I was 10 years ago." ("You were screwed," he adds with a laugh, referring to the three shows he directed that I was in late in the Eighties.) That sense of artistic development may be why, when asked to name his favorite productions he's directed, Webster weights the list toward shows of more recent vintage: A Lie of the Mind (1988), Blue Surge (2004), The Glory of Living (2006). ("For some reason, The Glory of Living was such a great group. I don't think I've ever seen a cast and crew that liked each other so much and got along so well. I was really sorry to see that one go.")

But then Webster does the same when ticking off his favorites as an actor: House (1999, 2001), Vigil (2002), St. Nicholas (2006, 2007). He even has Thom Pain (based on nothing) on the list already, just based on his enthusiasm for the script and his work performing it for friends and associates in rehearsal. It isn't that Webster's memory is failing; he's notorious for his total recall – "He's always watching, watching the actors, listening to the audience," Skola attests, "and after the show, he can recount every moment, each thing an actor did or any audible audience response" – and, indeed, during our interview for this feature, Webster is able to provide the specifics of productions (not to mention quotes from reviews) throughout his three-decade career. He remembers it all. He just favors what he's been doing lately. He has his head in the game today.

The Streak

Even so, what is it that keeps Webster plugging away, when he's more than earned a rest on his laurels? I mean, after a while even Cal Ripken called it a day. According to Catmull, he soldiers on in theatre "because he knows that the likelihood he'll be hired to manage a professional baseball team gets smaller every day." Skola has a take that's a bit less tongue-in-cheek: "I can't imagine Ken doing anything else other than theatre. Ken has a lot to say, and it seems he found a way to say it [and say it well] through theatre and stuck with it. I think he still does it because, like many informed and passionate people, he still has a lot to say. He's an opinionated person, and in choosing works that speak to him, I feel as though he, in turn, communicates a lot to his audience about art, humanity, and the world around us."

For his part, Webster says, "One of the reasons I still do it is I'm fortunate enough to do the plays I want to do. And throughout the time I've been doing theatre in Austin, that's been the case almost exclusively. From 1979 to today, I can count on one hand the number of plays I didn't really want to do." He gets to do the plays he wants with people he likes; he has his own theatre in which to play and a board that supports what he does. That would seem reason enough to keep going, but Webster offers up one more rationale, and it may be the most important of all. "It's still so much damn fun," he says. "I had so much fun doing House. I had so much fun doing St. Nicholas. This morning, when I woke up, before I made coffee, I was doing lines in my head." 'Nuff said.

Batter up! ![]()

Thom Pain (based on nothing) runs April 12-28, Thursday-Saturday, 8pm, at Hyde Park Theatre. 511 W. 43rd. For more information, call 479-PLAY or visit www.hydeparktheatre.org.