Slam as It Ever Was

The nationals come to town amid the polarizing medium's 20th anniversary

By Shawn Badgley, Fri., Aug. 4, 2006

It's nearing 2am on a Thursday morning, and I'm in an argument with two dudes at a South Austin dive bar. Don't worry: They're poets, semiretired. One – Penn Jillette in timber and ponytail, a little red in the face, broader than he used to be but by no means heavy – refuses to sit down, looming over me with more mischief than menace. Also, he won't shut up.

The other is measured and pensive, but by the look in his eyes behind the black-rimmed glasses, it's clear that he'll engage in the intellectual equivalent of holding my arms behind my back should his friend and colleague, a member of his wedding party way back when, give him the sign and start swinging.

The bartender wipes the counter. The jukebox plays songs, or it doesn't. Women gather. One is the big guy's wife; one or two or three – I don't remember who or how many – is a friend or a relative or a groupie, bringing him the occasional beer; and one is Genevieve Van Cleve, a poet who isn't semiretired or, for that matter, close to it. Which is why I was here at Ego's earlier, on Wednesday night, when 75 people gathered to watch her and a dozen others – including notables Big Poppa E, Andy Buck, and Christopher Lee – read, recite, perform, preach, sing, athleticize, rap, stand up, and deliver poetry ... or something.

"I don't know why you have to keep referring to it as a 'form,'" Van Cleve says, squinting at me. "What's with that? A 'form'?"

"People are not up to date with what slam is now," says Austin slam master Mike Henry, the guy with the glasses, who is about to become less measured and pensive. I've made the mistake of claiming that poet Mark Strand is better and has a larger, more-informed audience than Def Poetry Jam. "You would say that, because you don't really know what you're talking about."

"Some people don't like three-chord rock songs," says ponytail, aka Wammo, and to discern it in his stream of words is like grabbing a fish bare-handed. "Some people don't like slasher films. I mean, who cares? It's ridiculous. Somebody could go up onstage and take a big shit, and the notion of it being poetry might be in question."

If this isn't a sore subject for slam poets, it's certainly one they're sick of hearing about.

For the past 20 years (as Poetry Slam Inc. celebrates it), since Marc Kelly Smith founded the competitive art of performance poetry at the Green Mill Tavern in Chicago, they have endured the alternately valid and oblivious attacks of academics, of aesthetes and social critics, of various members of the vanguard and various members of the avant-garde and various members of the human race who might be aware of their existence; they have resisted bending to the whims of the acculturated hipster-leanings of the day, be they understated or over-the-top, ironic or earnest, cheap or expensive; and they have withstood the scrutiny of the tastemaking media, which loved them for almost 15 minutes in the mid-Nineties and is now much more concerned with, God, I don't know, graffiti. The cool-hunters have left them for dead.

So, why the hate, y'all? Why the ambivalence? Why the distaste? Surely, as a maturing but sustained way to make art, and one that rapidly made its presence felt in pop culture and entertainment, slam poetry is, on some level, burdened by potential. Skeptics have been able to track it since its birth, after all, to register its generational impact in real time. There is literary jealousy at its relative success, but also outright literary disappointment. Even for the appreciative, it's difficult to reconcile slam's "sport" with its "spoken word." And when past National Poetry Slam trophies have included a sword plunging through a stack of books – as if to say, "We want to kill you, books!" – a form has a little explaining to do.

But to wonder about its reputation and future, to ask around for some explanations, is to realize that slam poetry isn't really sweating it. Enough people continue showing up every week in enough big cities in this country and others. Not enough poets are making a living off of touring or publishing, say the poets, but enough good ones are earning a few extra bucks off of enough people paying covers. Enough of them are repeat customers. They're aging blue-collar bohemians still seeking everyday truths, pretty kids still looking for something to do after their retail shifts are up, family and friends. Actual random people attend, which must madden real poets. These random people make for ideal judges, in fact, who score the three-minute performances on a scale of one to 10 in a transparent process subject to the collective – and loud – oversight of people boozing and caffeinating. Or just having fun however they can.

They're still diverse, these audiences, in race and creed and orientation if not ideology. Some are into drugs, and some aren't. The scenes themselves remain loosely insular – there are wannabes, mascots, icons, lurkers, in-jokes, traditions, and feuds; there is politicking, incestuousness, and as much coupling as sexual tension – but accessible. They root for but are honest with, and often tough on, each other. There's an unmistakable sense of populism but also an unmistakable sense of code: both formal, as according to the rules of the game and of the venue, and unwritten, as with one's standing in the eyes of the regulars and elders. Observe, and you're a part of the community; stray, and you could be set adrift.

To be set adrift is to, in effect, be showing up on a regular basis for a glorified open mic. This might be fulfilling for the complacent or self-absorbed, but it is not for those hoping to resonate, subvert, and inspire. For a triumphant performance, connection with the audience is by definition necessary, and connection is more likely with the backing of the community. In other words, good slam poetry often bears the stamp of a scene, the nod of a select few; bad slam poetry finds its ancestry in the open-mic model. On any given night, what results is uneven at best, and the talent pool is diluted with work lacking subtext, overflowing with forced cadence, relying too heavily on identity, and straining with emotions that embarrass or manipulate.

The question then isn't whether that work is poetry or theatre or whatever – I mean, who does care? – but whether it's worth your time. Enough have decided that it's not.

"It does drive me crazy when poets are up there just pushing buttons and if they're just plying the audience for points," Henry says. "If they have forgotten about the writing. Or if they suck. But, if you don't like the show, wait three minutes. The good ones keep you going."

"The reason I still do this is because this is one of the only places in the United States of America that anyone, whether they're pedigreed or not, can sign up on a piece of paper and have three minutes to speak their peace," Van Cleve says. "Now, there's an artful way to do that, and there are weird rules, but I think slam poets are truth tellers. We find mendacity so incredibly distasteful that we are willing to endure the parlor game that is the slam."

"It's a really good medium for young writers and performers," Wammo says. "Who in the world would have a problem with that?"

It's a good point. Anyway, when you're standing at a bar going back and forth about this stuff with Henry, Van Cleve, and Wammo – three of the four cornerstones of the Austin slam scene; three of the four members of its inaugural national team in 1995 – and the National Poetry Slam is coming to town in two weeks, all you're really doing is wasting time. These people have things to do: Henry is the event's artistic director; Van Cleve will join the great Zell Miller III, the intense Da'Shade Moonbeam, the empathetic Tony Jackson, and the risk-taking Christopher Michael (whose wife left for a yearlong deployment in Iraq on Aug. 5) on a home team laden with talent and experience; and Wammo will be Wammo, busy playing with his band, the Asylum Street Spankers, maintaining his legacy as a "media smash," and holding forth at the "meeting place of bullshit and alcohol."

Speaking of which, Phil West is that fourth cornerstone and member, a former contributor to this publication, and a husband and father living in far South Austin. He's compact, multidegreed, recently quit smoking, wants to "get back into soccer," and is enthusiastic about the National Poetry Slam – not just because his company is doing the PR work for Austin's hosting of it. It's common for someone in my position to dread dealing with PR people, but dealing with West means hearing good stories about classic slam confrontations, like the one Austin lost to rival Dallas at the late Electric Lounge in 1998, the last time the NPS was here, and about legendary competitors like, well, himself.

"I almost feel like a geek discussing these 'battles,'" West says on a drive to San Antonio to scout the city's team (which includes father and daughter Anthony and Amanda Flores, as well as the formidable Rialistic) and check in on the weekly slam he used to host at Sam's Burger Joint. "But they were pretty spectacular. We were pretty spectacular."

West and Henry share an office in 501 Studios that doubled as a production headquarters for the documentary Slam Planet (see p.84) after the Guadalupe Arts Center burned in a 2005 fire. On the floor is giant papier-mâché likeness of Wammo's head. The duo is leading the effort to coordinate the 73 teams and 350 artists who will compete across eight venues starting Aug. 9.

West and Henry's notes on attending teams – Kalamazoo is surprisingly strong, the NYC Nuyoricans always have a different team but always have a chance, and watch out for Rachel McKibbens or Anis Mojgani, etc. – carry with them a certain removal for me that goes beyond geography: There's a reasonable expectation about the shape that performances and the tournament itself will take – as there is on, say, selection Sunday of the NCAAs – but the possibilities, variations, and scenarios are many. It won't shock you to see what power words have, what a human body can do onstage, how a human voice can shake a room, but the effect hinges on the experience; as much depends on that stage and on that room as on those words. A lot depends on the host who randomly – but, as West admits, demographically – selects that bout's judges. Visitors will have to combat the home-field advantage, but all teams will have to cope with the moods, expectations, and preferences of the people. Not even the savviest and most charismatic artists are impervious.

Still, I can't imagine anyone not responding to a team that Henry introduces me to at Antonio's Tex-Mex on the I-35 access road near 183, a pleasant enough if a bit well-lit restaurant surrounded by off-ramp motels. When I watch them practice the next night, I find it hard to believe that anyone will beat them.

The Austin Neo Soul Lounge is a slam founded by Herman Mason of South Flavas Entertainment and Ron Horne of the Texas Youth Word Collective. It's in its fourth year and venue. It takes place every Wednesday night, overlapping and cross-pollinating with south-side stalwart Ego's, which, since the Electric Lounge shuttered, sponsors what has historically been the city's only team.

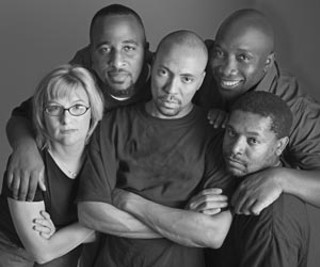

2006 will be the first time that the simultaneously explosive and laid-back Neo Soul will have a representative team at the NPS, although members Kim Taylor and Trey Stepter have nationals experience. Taylor is a force, hypertalented and focused, while Stepter is nicknamed "Quincy" for his ear. In his debut slam at Ego's last month, he finished third. The team – rounded out by Michelle Desiree, Joe Brundidge, and Brian Francis – has won two of its six regional scrimmages. After 33 practices in the past two months, they are peaking at the right time.

"The sense of competitiveness hasn't eaten us yet," Taylor says. "But some of us are competitive. We don't have buckles yet, nothing to signify what we've done at nationals, but now comes the fun part. I think that we are probably the most prepared team going in. We've repeated only one piece in all of the scrimmages that we've gone to. We've managed to earn a lot of respect in not a lot of time."

"It's a competition, clearly," Brundidge says. "But we don't want to overstrategize or play too much to the judges. As cliché as it might be, we just have to do our best and believe in what we're bringing."

"We're hoping that your article won't keep us from sneaking up on people," Francis laughs. "Regardless, we'll be in the mix."

The portion of practice No. 34 that I watch at Francis' two-story home in Wells Branch centers on a group effort called "The Box." It's dynamic, involving all five members, and features the silver-tongued Desiree delivering a relentless and vibrant lyric over layers of beat-boxing and a cappella bass and melody. It is as smooth and precise as a good watch; as they perfect it, coming closer and closer to what they – and their adored but demanding coach, Mike Whalen – are after, it invariably comes in at two mintues and 44 seconds. Though built on timing, it is somehow unpredictable.

"Sometimes it works, and sometimes it doesn't," Stepter says. "You have to deliver a piece to the point where you know you are actually making an impact on somebody."

"We're not what we look like," Taylor says. "We can't be pegged. That can only make us stronger. We don't do 'black poetry,' or at least what people might think of as black poetry. We're not selling out, but we're much more abstract, and we each bring different things. We complement each other. What we want to do is try and appeal to everybody. We can beat you in more than one way."

Later, as the rehearsal winds down with Desiree and Taylor struggling through a problematic piece, there is laughter and a sense of eagerness rather than anxiety. Whalen stands, his punctuated body language offering advice on accent and pace, while Brundidge and Stepter study something on a laptop screen. Pizza plates, Fanta bottles, and wine glasses must be picked up. Francis leads me upstairs to the "Wall," which is in a lofted area decorated with framed black-and-white photos. His teammates are up there. Members of the Ego's team are up there. Everybody on the Austin slam scene, it seems, is up there. It's an archive and a tribute, but it's also proof that they're all part of something.

No one in the pictures appears to be overly concerned about how people who want nothing to do with that something – whatever it is – will look at them. ![]()