... And the 'West' is History

How Big State's little monologue show changed Austin theatre

By Robert Faires, Fri., April 7, 2006

The Chronicle theatre listings for Nov. 1, 1985, give no real indication of a seismic shift in the offing. The shows listed are a pretty standard mix of hardy perennials (Bus Stop, All My Sons, Vanities, West Side Story) and fairly recent transplants from more fertile theatrical soil to the north and east (Betrayal, Ain't Misbehavin', Painting Churches, Moonchildren). Among the 18 productions are several Austin originals (Sheila Tesar-Carr's Freelance, Carlos Morton's The Many Deaths of Danny Rosales, Alice Wilson's Razzmatazz, Mary Alice Carnes and Franklin D. Lewis' Jalapeño Sam as Seen Through the Eyes of Frankie Dan, a short-lived live soap opera, Downtown, by Lin Sutherland), sign of the newly burgeoning playwriting scene, but they attract only modest attention, certainly nothing on the order of a Greater Tuna – at that point, four-years-old and already keeping its creators and stars, Joe Sears and Jaston Williams, busy performing across the nation.

One show, however, stands off a little from the rest. Over its listing sits a black bar with the word "Recommended" reversed out on it. It's for a new show called In the West, featuring monologues written and performed by the members of a still new independent company called Big State Productions. Now, the previous couple of seasons had seen productions of the Robert Patrick play Kennedy's Children and Jane Martin's Talking With..., both collections of monologues, so it wasn't as if an all-monologue show was a novelty. Still, there was reason to be hopeful that this show might be something ... different. Though Big State had been around less than two years, it had produced three strikingly original shows: an obscure and rather bizarre drama about God, Lucifer, and the creation of sexual disease called The Council of Love, Terrence McNally's post-apocalyptic black comedy ...And Things That Go Bump in the Night staged in the basement of a used bookstore, and a poetic, revelatory Our Town that blew all the dust off Thornton Wilder's classic and made it lyrical and cosmic and moving. In this time before the Rude Mechs and Salvage Vanguard and Physical Plant, before the Vortex and Refraction Arts and Rubber Repertory, this was our experimental theatre company, the most daring, the most innovative theatrically, with a corps of talented young artists willing to take risks. So if they were doing a monologue show, and they wrote it all themselves ...

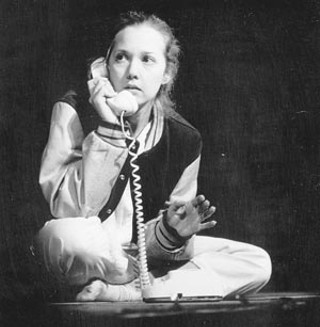

The first performance, on Nov. 2 in the Mary Moody Northen Theatre on the St. Edward's University campus, told the story. At the end of the show, audience members went wild, leaping to their feet and, according to Big State's artistic director, Jim Fritzler, who had conceived the show as "a little actor's showcase kind of thing," "they all ran down on stage and started talking at once." The next week, the show moved to the Elisabet Ney Museum, and word of it had spread like wildfire, so that both performances that weekend and the two the following weekend were "swamped with people." Their response was every bit as exuberant as that of the opening night crowd. This writer, who hadn't planned on reviewing the show, dashed off a 2,000-word feature review for the next edition of the Chronicle. (It's available online as a Web extra.) What we were all responding to was not something radical in terms of theatre; on the whole, In the West was very traditional – the monologues all straightforward narratives, the characters all recognizable human beings, the staging simplicity itself: one actor at a time, lights up, lights down. But it was funny and smart and sharply observed, and it showed us people we knew and was profoundly generous to those people and to the audience. As I wrote then and still feel, "It does not merely show us glimpses of Westerners' lives; it invites us into them, sharing with us the intimate details, the joy and blood and tears."

This became one of the first shows since Greater Tuna to be successful enough to warrant reviving, certainly the first locally generated show to be that successful, and In the West was revived a dozen times over the next six years. As noted in the companion article, it was also one of the few shows at the time to travel beyond Austin's city limits, playing Dallas and Fort Worth and, in what stands as its valedictory engagement, the nation's capital – one of the few theatrical productions in the entire Lone Star State to be invited to perform in the Texas Festival at the Kennedy Center in 1991. This was significant, as in those days, no local theatre artists outside of the Tuna guys and playwright Marty Martin (Gertrude Stein Gertrude Stein Gertrude Stein) had made a splash on the national scene. And how extraordinary for it to happen with such an offbeat show: with all those people all doing little solo turns written by them or their friends.

That's where Big State broke the rules with In the West, by creating something with so many people and never backing away from it. As time went on and success bred more opportunities, it might have been prudent to pare down the cast and settle on a final list of monologues. But Big State always kept the cast around a dozen and kept the show evolving every time it was presented. New monologues were generated, until there were more than 50 in the repertory. Actors rotated in and out, so that certain monologues might be performed by different people from show to show. The more In the West was revived, the more it resembled a concert as much as a play, with the cast creating a set list for each gig and assigning pieces to whoever was on hand to play that night the way a band might divvy up solos. Maybe that's one more reason it appealed so much to this music-driven city.

The show also broke open the idea that writing for the stage was the province of the trained dramatist. In the West was proof that everyone has stories to tell and might well have the talent to tell them on stage. In fact, within its first couple of years of In the West, company members found themselves receiving not just raves about the show from people on the street but monologues those people had written as a result of seeing the show. As Big Stater Joy Cunningham put it, "It's nice to have the clerk at the grocery store tell you he saw you in a play and enjoyed it. It's something else to have him tell you he saw you in a play that so moved and inspired him that he went home and wrote a monologue himself and would be honored if you'd take a look at it."

There's no way to know how many people might have been inspired to write traditional, multicharacter plays by Big State's runaway hit, but in the wake of In the West, it was easy to see a wave of Austin-penned monologue shows. Big State itself was responsible for two – The Big Event and In the Spirit of the Magi: Counterparts – and individual Big Staters developed several others: Marco Perella's Tarot for a New Age, C.K. McFarland's Earth Angels, Rick Perkins' O. Henry's Will Porter: The Rolling Stone, John Hawkes' Nimrod Soul, Jo Carol Pierce's Bad Girls Upset by the Truth, Joy Cunningham's Goin' to Georgia.

But many others followed, both those featuring multiple characters – John Henry Faulk's Pear Orchard, Texas; Timothy Miller's The Storyteller; Libba Bray's High Hopes and Heavy Sweatshirts; Lindsay Lane's The Miracle of Washing Dishes; Donna Stevens' and Suzanne Chesshire's I Married an Ignoramus and The Donna Show – and those featuring a single voice: Terry Galloway's Out All Night and Lost My Shoes and Lardo Weeping; Cactus Pryor's J. Frank Dobie; Larry L. King's The Kingfish; Jerry Flemmons' O Dammit!; and the list goes on and on. Most had no direct connection to Big State or In the West, by way of artistic connection or inspiration even, but all benefited from In the West's ongoing success, which made it clear solo performance could thrive here, that this was a place where audiences would come see it and where locally written drama in general could grow.

In 1991, film director Stephen Purvis saw In the West and was moved to put it on the silver screen. He optioned the script, shot a trailer, and began raising funds for the film, which came to be titled Deep in the Heart (of Texas). Four years later, he completed the film, which features a number of actors from the original cast, and it had a brief life in the cinema. But it's not really In the West. What made that show the phenomenon it was had everything to do with theatre, with it being live and intimate and changing with every performance. That's why folks kept coming back and why its memory and impact are still felt to this day. ![]()