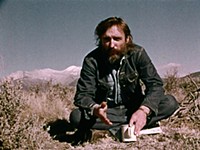

In Memory of Dennis Hopper

'A walkin' contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction'

By Louis Black, Fri., June 4, 2010

"He's a poet, he's a picker,

He's a prophet, he's a pusher,

He's a pilgrim and a preacher

And a problem when he's stoned

He's a walkin' contradiction

Partly truth and partly fiction

Takin' every wrong direction

On his lonely way back home ...

There's a lot of wrong directions

On that lonely way back home"

– Kris Kristofferson, "The Pilgrim: Chapter 33"

"The next morning in the parking lot, at 6:30, at the top of his lungs: 'This is my movie! Nobody is going to take away my fucking movie! You got it? This is my fucking movie ....'

"This time his voice gave out after only one hour, and we started filming by nine-thirty. Dennis was two-for-two in the batshit department, transformed into a little fascist freak I'd only glanced before."

– Peter Fonda reminiscing about the first two days of shooting for Easy Rider in New Orleans in Don't Tell Dad: A Memoir

There were chunks of his life where it seemed that he must have no other goal than to kill himself. There were other, larger chunks, and more of them, where not only did he seek redemption and justification but worked at such a peak as to hit transcendence. Enfant terrible, renegade actor, Hollywood rebel, post-Beat crazy visionary, stoned-out celebrity, industry maverick, actor, writer, director, photographer, artist, and collector Dennis Hopper died from complications resulting from prostate cancer on May 29, just days after he turned 74. Larger than life (larger than several lives), following the path of excess both up to wisdom and down to the deepest depths, Hopper, his relationships, talents, work, and creations can barely be described in words, much less contained by them. Talking about him is like trying to stuff large quilted blankets into an already overstuffed box; there's just too much to him. Always excessive when it came to consumption, creation, appetite, and vision, Hopper was never shy about expressing his opinion nor modest in describing his accomplishments and assigning himself credit.

Hopper was an inspired actor and a gifted director. Most importantly, however, he saw himself as a cultural provocateur, forever questioning the present while openly scoffing at the past.

It was in Houston. Richard Linklater was there or else I'd probably believe this story to be apocryphal. A performance piece: Dennis Hopper, sitting in a circle of dynamite, all the sticks pointing outward, lit the fuse. The dynamite blew. He was all right. Evidently if every stick blows, the center is safe, if one doesn't however ....

It is so tempting to use this performance as a metaphor for Hopper's career, but any single idea, any lone image, no matter how expansive in its meaning, would fall short. Almost every Hopper obit will begin by citing Easy Rider, the 1969 film Hopper directed and co-wrote and co-starred in with Peter Fonda. This is appropriate, but it is also limiting. Given his life and work, there is obviously much more to his story.

Easy Rider revolutionized the film industry and impacted the overall culture. Produced for about $400,000, it earned $19 million at the domestic box office, $40 million overall. This was a fantastic box office gross as well as a remarkable return on the investment.

Not exactly understanding why the film was so successful, Hollywood executives figured it had to be because young people made it. Consequently, they gave everyone they could find who had ever touched a camera the go-ahead to make a movie. Even though most of these films bombed, many of the new talents remained in the film industry.

After Easy Rider's release, Hopper and Fonda were as hot as they ever would be in the film industry. This allowed Hopper to follow with a project of his own choosing, The Last Movie. While it was in production and post-production, there was widespread anticipation in the industry. Finally finished and actually seen, it was widely dismissed and intensely disparaged. The Last Movie goes hand in glove with Easy Rider, the yin and the yang, the unexpected success and the once eagerly waited for failure that followed.

Hopper spent 22 weeks editing Easy Rider, screening a new cut each week. The Last Movie took longer. (The shoot had been bad enough with constant partying and excessive drug use. Some of the cast and crew had taken to carrying plastic Johnson's baby powder containers filled with coke; they'd tap it out on the back of their hand, snort it, and just wipe away whatever was left.) Hopper had decided to edit in Taos, N.M., a bad idea by anyone's standards. Renting the house that had belonged to Mabel Dodge, he began editing. Soon it was so filled with hangers-on and nonstop partiers that Hopper had to move across the street to another rented house. The monthly liquor bills were in the tens of thousands.

It is amazing that this one film, Easy Rider, and its far less seen shadow and/or doppelgänger, The Last Movie, have managed to overshadow all the other works in Hopper's long, amazing, and varied career.

Beginning very early in his career, Hopper was determined to create his own way in the world. He appeared in both Rebel Without a Cause (D: Nicholas Ray; 1955) and Giant (D: George Stevens; 1956), where he was awed by star James Dean. The two, both interested in pushing past the boundaries of the known in service to their art, became fast friends. Essentially, Hopper spent most of the rest of his career aspiring to trailblaze the unknown, to create work as unprecedented and visionary as Dean's. Necessarily, this meant making films that were honest, raw, unique, and immediate, untainted by any required adherence to simple, dumbed-down, gutted, stale, hackneyed, and traditional standards. The only way to achieve these ambitions was to stay focused and steadfast, guided only by his own integrity, morality, and sense of responsibility. Typically, Hopper, of course, took this further than was necessary in that he didn't just ignore industry's expectations and standards but actively verbally demeaned and dismissed them.

In the 1965 film The Sons of Katie Elder, he ended up in a blood feud with legendary old Hollywood director Henry Hathaway, resulting in Hopper being informally blacklisted. This was the motif for Hopper's career: three or four steps forward, half a step backward – but one so over the top in its execution that it attracted all the attention.

Just considering his astounding overall body of work easily refutes the worst of Hopper's reputation. An outstanding actor, some of his greatest work is in Wim Wenders' The American Friend (1977, with Bruno Ganz), Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979) and Rumble Fish (1983), and Sam Peckinpah's The Osterman Weekend (1983). There is also Blue Velvet (D: David Lynch; 1986), River's Edge (D: Tim Hunter; 1986), and Black Widow (D: Bob Rafelson; 1987). These of course would be along with his Emmy-nominated performance in Paris Trout (D: Stephen Gyllenhaal; 1991) and his Oscar-nominated performance in Hoosiers (D: David Anspaugh; 1986), one of the greatest of all sports movies.

In the last couple of decades of his career he appeared in a number of over-the-top roles in films such as Super Mario Bros. (D: Rocky Morton; 1993), True Romance (D: Tony Scott; 1993), Waterworld (D: Kevin Reynolds; 1995), and, of course, Speed (D: Jan de Bont; 1994). It also seemed as if he was offered few roles in out-of-the-mainstream productions that he turned down, no matter how uncertain, unique, or idiosyncratic the production. Invariably, when he did accept a role, he gave it his best. These included Orson Welles' unfinished epic The Other Side of the Wind; Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986), rumored to have been great before being re-edited and mutilated; and Alex Cox's punk Western Straight to Hell (1987), co-starring Joe Strummer, Grace Jones, and the Pogues. Hopper also acted in cult director Henry Jaglom's Tracks (even weirder than the eccentric talky films for which he is known), the cult classic Kid Blue (D: James Frawley, script by Bud Shrake; 1973), Neil Young: Human Highway (1982), and crazed director James Toback's The Pick-Up Artist (1987).

Even with all the titles listed above, there are any number of films Hopper acted in that aren't listed. He also continued to direct, following Easy Rider and The Last Movie with Out of the Blue (1980), Colors (1988), and The Hot Spot (1990). Hopper was also an acknowledged and acclaimed collector and artist (a photographer, painter, poet, and sculptor). It's been announced that Dennis Hopper's work, curated by Julian Schnabel, is going to be new Director Jeffrey Deitch's inaugural show at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Yes, he was always crazy, maybe not as completely tapped out as Rip Torn but close. He was of a loose generation of crazies, including Jack Nicholson, Warren Oates, and Bruce Dern, lacking any anchor to earth and normality and whose madness was matched only by their acting talent.

Dennis Hopper sped through most of his life with a pedal to the metal intensity that left not just normalcy behind but just as often acceptable human behavior. Driven by a commitment to personal vision and an unshakable integrity, he really had no other choice as how to live. Always inner-directed, Hopper was never in thrall or even very respectful of the social mores, whims, infatuations, and ever-shifting sensibilities of the outside world. He lived in a world that was of and as defined by Hopper. Neither his vision nor integrity were deeply rooted in any ideology, traditional body of philosophical thought, or religious belief. Instead, as certain, unbendable, and controlling were his beliefs, they were also nonspecific, often shifting characteristics and mores. Despite uncertainties, he was certain. In spite of his changing perceptions, he was unchanging. Everything about Hopper's career is greater than the sum of its parts, but it is hard to imagine he would have wanted it any other way.

For further thoughts on Easy Rider and The Last Movie, read "Remembering 'Easy Rider' and 'The Last Movie'," the CinemaTexas program notes written by Ed Lowry, Nick Barbaro, and Louis Black.