Do a Little Dance

By Marjorie Baumgarten, Fri., Feb. 12, 1999

Ask several thousand people to define "independent cinema" and you're liable to come away with several thousand answers. Is it a monetary definition? A budget under $10 million? Five, or one million? Or is it possible to define independent filmmaking by its aesthetic, attitude, or sensibility? Maybe the form is predicated by its funding source, whether a film is financed by a studio hierarchy or by scrappy self-determinism (you know, all those near-mythic stories about credit-card financing, questionable insurance settlements, and filmmakers selling their bodies as medical lab rats). Or perhaps all it requires is evidence of a clear artistic vision or individualistic voice. Is it possible for a major studio to produce an independent film? (The distinctive vision of Disney's Rushmoreprovides a good current example.) And conversely, can an independent company produce a commercial blockbuster (like Miramax's Scream franchise) or an expensive arthouse hit (like The English Patient -- also Miramax)? Ultimately, the most honest answer may be to simply define independent film in the same way that Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously described obscenity: I know it when I see it.

Ask several thousand people to define "independent cinema" and you're liable to come away with several thousand answers. Is it a monetary definition? A budget under $10 million? Five, or one million? Or is it possible to define independent filmmaking by its aesthetic, attitude, or sensibility? Maybe the form is predicated by its funding source, whether a film is financed by a studio hierarchy or by scrappy self-determinism (you know, all those near-mythic stories about credit-card financing, questionable insurance settlements, and filmmakers selling their bodies as medical lab rats). Or perhaps all it requires is evidence of a clear artistic vision or individualistic voice. Is it possible for a major studio to produce an independent film? (The distinctive vision of Disney's Rushmoreprovides a good current example.) And conversely, can an independent company produce a commercial blockbuster (like Miramax's Scream franchise) or an expensive arthouse hit (like The English Patient -- also Miramax)? Ultimately, the most honest answer may be to simply define independent film in the same way that Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously described obscenity: I know it when I see it.

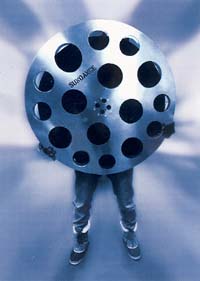

Thousands of people with thousands of answers (and even more questions) were rushing around the tiny resort town of Park City, Utah for 10 days in late January at the Sundance Film Festival. With 114 features and 58 shorts in this year's program, the festival is this country's biggest and most important annual showcase of American independent film.

But has Sundance become a victim of its own success? In trying to be so many things to so many people has the festival lost its direction and sense of purpose? Or is it that filmmakers are tailoring their projects to appeal to the widest possible audience now that the last dozen years have demonstrated the commericial viability of select independent films at the box office? Festival attendees generally grumbled about both.

This year at his welcoming brunch, festival host Robert Redford for the first time acknowledged that Sundance has become a "market," a term he has resisted using until now in favor of the loftier vision of the gathering as a showplace for Hollywood alternatives. According to Variety, the number of films sold at the festival was among the highest in the event's 15-year-long history. However, the amounts distributors paid for the films this year was noticeably down. Most films sold in the $1 million range, a noticeable decrease from last year when Miramax shelled out $6 million for Next Stop, Wonderland, or from 1996 when the record high price of $10 million was paid by Castle Rock for The Spitfire Grill. At the box office, neither of those movies came anywhere close to recouping their investment costs. Yet all it takes is the phenomenal break-out success of a festival movie like Shine, Clerks, Welcome to the Dollhouse, or Reservoir Dogs to prove that there are sometimes immense profits to be made by picking up a low-budget indie and marketing it successfully.

That may explain the bidding war that broke out over Happy, Texas this year. This crowd-pleasing comedy about two escaped convicts (played by Jeremy Northam and Steve Zahn) who hide out in a small town and masquerade as homosexual beauty pageant directors appeared to be one of the few films that exhibited real potential for a successful multiplex crossover. The movie, which also stars William H. Macy as the local law officer, could be described as a cross between Some Like It Hot and In & Out, and virtually every distributor in town bid on it. It was the most contentious transaction of the fest, and rumors of bids that reached the $10 million mark circulated. But when the dust settled, Miramax once again walked away the winner, acquiring the film for a surprisingly low $2.5 million guarantee plus a potentially lucrative gross participation deal for the filmmaker Mark Illsley and his producers, a back-end arrangement practically unheard of for first-time filmmakers.

No other film was as avidly sought after as Happy, Texas. Simply put, it smelled like money and attracted buyers. Other narrative films at the festival might be described as interesting, adventurous, artistic, or accomplished, but few exhibited much commercial potential or the sense that they might thrive outside the rarefied atmosphere of the festival circuit. The grand slam winner, Three Seasons by Tony Bui, received three awards: the jury prize for dramatic competition, the audience award, and one for cinematography. It's received quite a lot of attention as the first American film to be shot on location in Vietnam, and it features Harvey Keitel. Most of the reviews, however, cited the film's magnificent visual imagery while also decrying its stilted dramaturgy. Such films as Judy Berlin by Eric Mendelsohn, who earned the jury's award for directing, and Treasure Island by Scott King, who earned a special jury award for distinctive vision, are both ambitious narrative experiments whose originality should be acknowledged even if their intents and objectives are at times inscrutable.

Guinevere, the directing debut of The Truth About Cats and Dogs screenwriter Audrey Wells, shows promise for its unconventionally depicted love story between a young girl and an older man as well as the luminous performance of The Sweet Hereafter's Sarah Polley. Another screenwriter-turned-director is Hampton Fancher (Blade Runner) who brought his psychological study of a serial killer, The Minus Man starring Owen Wilson, to the fest. Two debuts by actors-turned-directors were also generally well-received: Tim Roth's The War Zone and Frank Whaley's Joe the King. A Slipping-Down Life, which is based on an Anne Tyler story and was filmed in Austin, features the fine performances of Lili Taylor and Guy Pearce. And the sweet boy-meets-boy story, Trick, which also offers a plum supporting role to Tori Spelling, was an audience favorite.

Yet, festivalgoers in search of the kind of vivid, daring, and original works that were among last year's Sundance success stories -- stand-out films like Buffalo '66, Pi (*), High Art, and Smoke Signals -- were out of luck this year. The trend among the films I saw (approximately 25) was toward the more conventional. A weepie called The Autumn Heart that stars Ally Sheedy and Tyne Daly is excrutiatingly stereotypical, trite, and poorly constructed; Roberta by Eric Mandelbaum is a politically muddled odyssey that casts the usually kinetic Kevin Corrigan as the film's dour lead; Twin Falls Idaho, a film about conjoined twins made by real-life identical twins Michael and Mark Polish, sounds more provocative in theory than it is in practice.

Among my favorites at the festival was the documentary prize winner, American Movie by Chris Smith (American Job) and Sarah Price. The film focuses on the world of low-budget filmmaker, Mark Borchardt of Milwaukee. He is the kind of driven soul whose obsession with his movie provides the perfect role model for this festival. Another of my favorites was The Blair Witch Project, a low-budget marvel that sets new standards for spooky movies. Filmed as a mockumentary, this frightening tale about a group of filmmakers whose bodies vanish (presumably by witchcraft) but whose footage survives to hint at their agony, is filmed in a smart, visceral style that terrorizes the audience with much the same devastation as a snuff film.

Other trends? Coming-of-age twentysomething films seem to be on the wane; the documentary selections again comprised some of the festival's strongest offerings and were widely praised for their range; digital filmmaking, and lots more of it on the horizon; high-profile actors are popping up with greater frequency in these low-budget indies, a trend that may help illustrate the disintegrating boundary lines between the studios and the independents as well as the growing romance with proving one's street creds through an affiliation with an independent film; and the abundance of films that deal with the porn industry. Sundance had Sex: The Annabel Chang Story, a documentary about a woman who sets a new world record by having sex with 251 men over the course of one 10-hour day, and Slamdance had The Girl Next Door, a documentary about the life of Tulsa porn star Stacy Valentine.

Slamdance is a festival that began five years ago as a home in the margins for Sundance rejects. At this point the simultaneously conducted festival is nearly as popular as Sundance itself. With a strong lineup and increased media coverage, Slamdance is now in the ironic position of receiving over 1,700 entries for just over 60 screening slots (only 14 narrative features are in competition). With its makeshift screening room in a local hotel, the screenings have lower admission prices and are more informal than their Sundance counterparts (offering floor cushions for viewers and enthusiastic encouragement for their showcased filmmakers) and has fast become a center for younger filmmakers and audiences. In recent years many more alternative and ad hoc fests have emerged: Slamdunk, Lapdance, and Souldance, to name just a few.

Another trend discernible to these eyes? The ubiquitous Austin presence at the Sundance Film Festival. Austinites were everywhere I turned: from Richard Linklater, who served as one of the dramatic competition jurors this year, to the ever-present volunteers, whose coordinated efforts help the festival run smoothly. In the streets and at screenings I would constantly run into attendees from Austin: filmmakers, journalists, and festival programmers. Also quite visible were the films with Austin ties: two feature films that were shot here last year -- Toni Kalem's A Slipping-Down Life and Jeffrey Janger's Fools Gold. Former Austinite Tonie Perensky co-stars in Fools Gold with J.E. Freeman and Camryn Manheim, and frequent Austin comedy-circuit visitor Brian Malow co-starred in (and co-produced) the midnight feature Los Enchiladas. Austin cinematographer Deb Lewis shot the stunning-looking black-and-white drama Afraid of Everything, and Rob Sabiston and Tommy Pallotta's unique digital animation short Roadhead, screened at Slamdance. Add to that performances by the likes of Abra Moore, and it begins to resemble Austin at 8,000 feet high. Is it time to come down yet?

For complete catalog listings of the Sundance and Slamdance Film Festival programs (and other good info) see http://www.sundance.org and http://www.slamdance.com. Many of the films will eventually find their way to local screens. Look for several others to be showcased at next month's SXSW Film Festival.