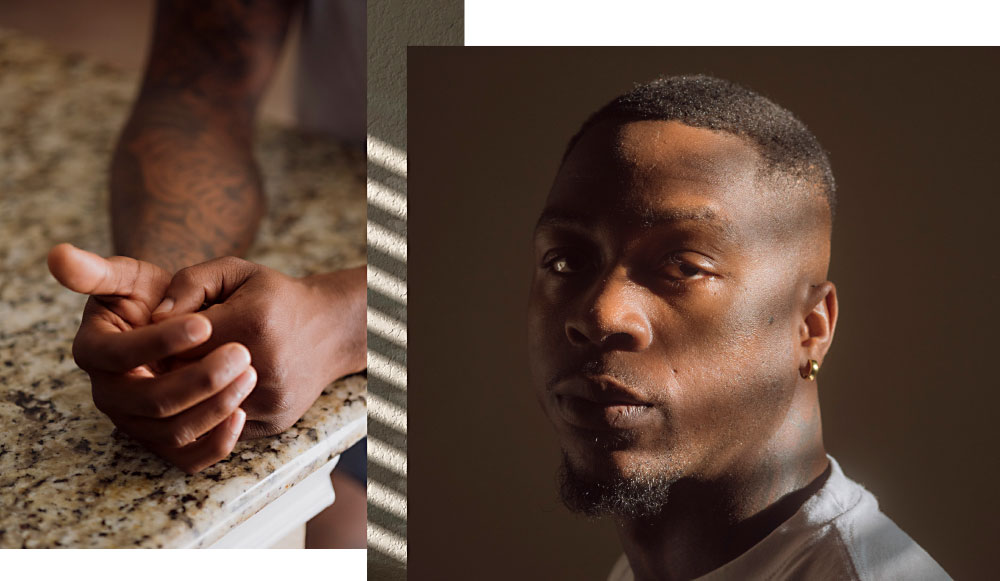

After Years in Jail for a Crime He Was Never Convicted of, Cyrus Gray Is Free ... for Now

Living in the free world, but the case just won't go away

By Brant Bingamon, Fri., Dec. 20, 2024

Cyrus Gray drove to San Antonio on July 28 of this year with a friend, a woman he doesn’t want to name. As he rolled south on I-35, he looked in his rearview mirror and saw police lights.

Gray pulled over to a gas station, thinking it would be the safest place for what was about to happen. Police cars parked behind him in a semicircle. More than 10 officers got out, their guns drawn.

“They’re standing there by the windows with their guns pointed at us, and we’re sitting in this car,” Gray remembered. “And all I’m thinking about is like, damn, this girl is right here. Look at this person going through this. This is terrible. The officers are yelling at me. 'Cyrus Gray, put your hands up! Get out of the car! Who’s in the car with you? Where are the guns? Where are the drugs? Who are you hiding in the car?’ I’m like, how did we get here? How did this get so extreme, so fast?”

Gray’s PTSD was surging. He got out of the car. He put up his hands. His perception shifted. “Time is froze right now. Time is froze. I’m walking slowly towards this cop. I don’t hear anything around me. I clearly see they’re shouting at me. I clearly see these cars all around. I’m walking. My hands are up. All I’m thinking is like, 'Damn, this girl is still in the car.’ And I get closer to the officer. He grabs me by the shirt, puts two pairs of handcuffs on me, and they throw me in the back of the car.”

Gray could see the outline of his companion from where he sat. He began to cry. “I’m rocking the car, going crazy. Like, 'Please put your guns down. Please put your guns down. Please put your guns down.’ This girl is in there, they’re yelling at her, 'Who are you hiding in the car?’ This girl is terrified. She’s never been through anything like this. I’m thinking, damn, both of us could be dead right here at any moment. It’s happened many times before, in less severe situations, with people who don’t have capital murder charges on their records.”

The officers took Gray’s friend out of the car. They put her on the ground, then in the back of a separate cruiser. Gray later learned that she begged them to be careful with him, told them about his PTSD. The officer who had handcuffed Gray returned.

“Now, at this point, he’s all calm. He’s like, 'Are you ready to talk?’ I said, 'What the fuck do you mean am I ready to talk? Do you see what you guys just did? Like, seriously, what the fuck was the reason for this? You guys all had your guns pointed at us. What was the reason? What justifies that?’ And then he slams the door back in my face and he leaves. I get arrested.”

Traumatized

The officers took Gray to jail and booked him for driving with an invalid license and two related charges. He spent the night in a freezing cell and was released the next day, July 29.

Gray’s experience that night was a familiar one. He lived nearly five years of his life, half of his 20s, at the Hays County Jail, after he and childhood friend Devonte Amerson were accused of killing Texas State student Justin Gage. Gray has now been free for two years, his charges dismissed in the summer of 2023. He has an apartment and a job and friends in San Marcos. He’s just beginning to process the trauma of his time behind bars.

Gray was 23 years old and working as a personal trainer in Houston when he was arrested. Born in Liberia, he moved to Chicago at the age of 7 and grew up as a lower-middle-class kid, quiet, self-sufficient, playing football and running track in school.

He had no criminal background. He was uncomfortable with violence. But because of the accusation against him – capital murder – Hays County jail authorities placed him in a “max tank,” a group cell for the most violent inmates. These were men in desperate situations.

“They were used to being in and out of jail, so they’re angry as hell,” Gray said. “And there were a lot of things that happened that I was dragged into, whether I was involved or not.”

A guard told Gray soon after his incarceration not to swing back if he was attacked, that he wouldn’t be punished if he restrained himself. The first time an inmate punched him, Gray took the advice. He said he was punished along with the other inmate. From then on, if he couldn’t defuse a fight, Gray fought back, becoming a version of himself that he now calls “Survival Cyrus.” Self-defense was necessary, because the Hays County Jail is one of the most violent in the state.

“I was constantly thrown in situations in violent tanks where you have to be vigilant at all times, you have to assert yourself at all times,” Gray said. “It was probably 15 times where there’s a situation, somebody has an issue. Okay cool, it’s a fight. Call me out. Let’s go. Because if you don’t fight, somebody else is gonna try you. And then the next person will try you.”

Gray says the guards encouraged the culture of violence and participated in it. He said he was attacked by guards half a dozen times. He described how they engineered fights between inmates, including, on two occasions, between him and others.

“The guards hated me because I speak up for myself,” Gray said, “and I would literally use their own rulebook against them – 'You can’t do that by law, by the rules and regulations that you go by, wearing that uniform, you can’t do that.’ They would hate that. They don’t expect you to try to learn or speak up for yourself. They expect you to sit there and take the abuse and take the violence until you eventually tap out and quit.”

Gray earned respect for his willingness to defend himself and challenge the guards but also for his concern and generosity. He counseled inmates on how to solve disputes. He helped them communicate with their attorneys. He comforted those who’d just arrived with things like fresh socks. Inmates gravitated to him.

One who did was Shawn Jackson, incarcerated in the jail from 2019-2020. Jackson credits Gray with helping him turn his life around. Gray had insisted he was innocent since first arriving in jail and he shared some of his story with Jackson. When Jackson was released, he researched the case. He became convinced Gray was telling the truth. He pestered a newly created social justice group, Mano Amiga, to support Gray at his upcoming trial. Mano Amiga hired Amy Kamp, a former editor at The Austin Chronicle, to look into the case.

Kamp had never talked to anyone in jail before she visited Gray. “He put me in touch with friends and family members, and I was hearing from more and more people and they were all kind of reinforcing the impression that Shawn had given of him, of this really good guy who really cared about other people,” Kamp said. “So I thought it was worth it for Mano Amiga to support him. It seemed like in Hays County, everyone was against him. He needed somebody to be for him.”

Gray’s trial arrived in the summer of 2022. It soon became apparent how little evidence the county had against him. Prosecutors argued that either he or Devonte Amerson – they couldn’t say which – had shot Justin Gage while trying to steal an ounce of marijuana. They presented cellphone records placing Gray and Amerson within 10 miles of the murder. They also had testimony from three men – two of whom recanted their claims under cross-examination – that Gray had spoken of a robbery gone wrong. But they had no eyewitnesses, no video footage, no murder weapon, and no DNA connecting Gray to the murder. The jury deliberated for four days before several of its members came down with COVID-19 and the judge declared a mistrial.

Kamp attended every day of the trial. It astonished her. She felt the testimony validated everything Gray had said. Mano Amiga decided to put Gray on its payroll, collecting information on injustices at the jail and assisting inmates. The nonprofit also organized an effort to get his $250,000 bond reduced, so that he could make bail. On Nov. 9, 2022, the bond was lowered to $70,000. Gray was released the next day.

Survival Mode

Gray dove into advocacy with Mano Amiga after his release, despite the fact there was still a capital murder charge hanging over his head. He spoke at a news conference in January of 2023 to draw attention to the killing of inmate Joshua Wright, shot in the back during a visit to a local emergency room by a Hays County guard. Gray told the audience about his own experience with the officer, Isaiah Garcia, saying Garcia had engineered his beating by fellow inmates the previous year.

Gray had never been a public speaker before and claimed it made him uncomfortable. But he was a natural. The appearance was the first of many. He spoke before the Hays County Commissioners Court, advocating for the creation of a public defender’s office. He spoke before the Texas Commission on Jail Standards about corruption in the jail. He told his story at community events. He also wrote articles for local media, met with attorneys, and raised funds for Devonte Amerson’s defense. And he worked to help the men he met in jail, including Myles Martin (later acquitted at trial after three years behind bars), Daniel Castillo, Joey Vargas, Lamount Harvey, and Melvin Nicholas.

“I was going to the courthouse pretty regularly, just observing, because I plan to go to law school,” Gray said. “There were people that I was incarcerated with, and their families would reach out to me and be like, 'Hey man, do you think you could come out to support us?’ And I would go sit there to support them. And it was like a scary movie when I’d go to the courthouse, because of the way the eyes were looking at me.”

Gray said that police officers tried to intimidate him at the courthouse. He said on one occasion an officer made a finger pistol, pointed it at him, and pulled the trigger. He said on another occasion a detective who had testified against him at his trial goaded him in a hallway, asking, “Do you remember me? What’s my name?”

Gray wouldn’t be intimidated. He believed his presence was useful to those he sat with. “I see how the judge responds to them differently from me being there, and from somebody being there in general. You know, a lot of people go to court alone, and when you’re alone it’s easier to maybe believe that you’re this bad guy, or you’re this crime, that the state of Texas is trying to portray you as. There’s a question like, 'Well, where’s everybody? Nobody cared enough to show up. This person must be a bad person.’ When, in reality, your family’s out there struggling. They can’t take off a day of work to be here for court or they might get fired or something.”

For nine months after he was released, Gray lived with Shannon FitzPatrick, a retired attorney at the Hays County District Attorney’s Office who offered him her spare bedroom. FitzPatrick attended hearings on Gray’s case, arguing beside Mano Amiga that Hays County should drop the capital murder charge and give up on a retrial.

Behind the scenes, Gray and his attorney disagreed on how to proceed. At a hearing in June of 2023, the attorney withdrew from the case. As the two stood before the judge finalizing the decision, Gray presented a motion he’d written himself the night before, arguing that the case should be dropped because he had not received a speedy trial. The judge read it over, agreed it was valid, and set a hearing on it. Less than 30 days later, District Attorney Kelly Higgins announced he was dropping the case. But he dropped it “without prejudice,” meaning that the county could decide again at any moment to press the capital murder charge once again.

With the charge dropped, Gray concentrated on getting Devonte Amerson’s bond lowered, like his had been. The bond was lowered in December of 2023. Amerson was released after waiting nearly six years for a trial. Though Hays County still hasn’t dropped the charges against him, Amerson’s release was, for Gray, an opportunity to step beyond the fight-or-flight mode he’d been in since 2018. Doing so allowed the trauma of those years to bubble up.

“With Devonte actually coming home, I guess subconsciously my mind was finally like, okay, it can kind of rest now. And then everything just hit me all at once, where I was just dealing with the mental anguish. I’d be on the highway going to see my girlfriend or something, and then I’d just randomly start crying out of nowhere. The trauma broke in.”

Balcony and Therapy

The mental anguish intensified after Gray’s July arrest. The incident sent him back into Survival Cyrus mode. Feeling overwhelmed, he sat on the balcony of his home for four days, going without sleep, smoking cigarettes, and writing a book-length manuscript.

“It’s 13 chapters, it’s a real book,” Gray said. “It details my situation, my real experience, me dealing with the system, what I learned through the process, how I feel about it, where I was at. It goes into some deep stuff, my childhood, my family and love life and all that, just how everything has impacted me, where I was at mentally before the arrest, how the arrest happened. It has some stuff about what should have happened, about certain situations, everything up to now, pretty much.”

Writing the book helped Gray realize he needed emotional help. He had never sought therapy before. He found the idea distasteful. But he decided he had to try it. In his first sessions, he looked for ways to discredit the experience. After the fifth session, he began to buy in. When we spoke in early December he’d been to nine sessions.

“And therapy still sucks, by the way,” Gray said. “Honestly, I hate that I have to go to therapy. But I also understand that, hey man, you got to go to therapy. You have to. You have to get past this, mentally. Because mentally, it’s hindering me from reaching the next level of myself that I want to be. And I refuse to put all of this on my loved ones. So maybe it’s best to go to therapy and put it all on a stranger.”

As part of the effort to care for himself, Gray has stopped going to the Hays County courthouse, at least for now. He has intensified his work for Mano Amiga, however, concentrating on building a reentry program for recently released inmates and others in the community. The program will include collaboration with Texas State University and be modeled on a reentry program created by Stanford professor Matthew Clair. Gray began corresponding with Clair while still in jail in 2020 and visited him this July to see Stanford and Clair’s program in San Jose, Calif.

Gray said the program he imagines will identify clients, work to understand their needs, and help them with housing, transportation, and mental health services. It will determine what skills they have and how to enhance them and connect them with employers. It will help them navigate court appearances and help with court fees and documents. It will seek to create a community around the client, to put them in touch with others who’ve had the same struggles, to make the psychological transition easier.

The goal, in criminal justice terminology, is to reduce recidivism. Gray thinks of it more simply – to care for people who need the help. He remembers the care he got when he was released.

“I came home and had a lot of support with Mano, with Shannon, Matthew Clair,” he said. “I had a support system already. Your average person who is coming out doesn’t have that. And even for me, it was very difficult to reenter mentally, financially, with employment. Luckily, Mano hired me. But had they not, I don’t know where I would have found employment. I don’t have a college degree. I didn’t finish college.”

As he works on the reentry program, Gray has continued to volunteer in the community. He helps people get new driver’s licenses. He recently helped Joshua Wright’s mom wash her car.

“People out here are struggling,” Gray told us on Nov. 26. “So my situation, however impactful or influential it may be, I want to take advantage of that and use that influence to help to get these resources established for the community. It’s a lot going on in my life. But I’m the kind of person that’s going to flourish under any circumstance or condition.”

Re-Indicted

On Dec. 16, Gray learned through Devonte Amerson’s attorney, David Sergi, that Hays County prosecutors were planning to file a new indictment against Amerson for capital murder in the killing of Justin Gage. Prosecutors filed the indictment the next day and added three new charges – murder (the simple charge, rather than capital murder), aggravated robbery, and burglary of a habitation.

Gray hasn’t heard whether prosecutors plan to re-indict him, but because his case is inextricably bound to Amerson’s, he fears they will. When we spoke, he sounded tired, beaten down.

“It’s messed up and diabolical,” he said. “But all it is is an attempt to either get us to flip on each other or to take a plea deal. There’s not anything to suggest that it makes sense.”

The Hays County D.A.’s Office had not responded to questions from the Chronicle as of press time Wednesday, Dec. 18. Sergi characterized the additional charges against Amerson as a Hail Mary by Hays County prosecutors, one last chance to wrest some kind of victory out of the case, even if it’s just a conviction for burglary.

“It shows the state’s absolute desperation,” Sergi said. “I think that they want to give a jury the opportunity to convict Devonte of something, but it is an absolute abuse of power and discretion. They know they didn’t have the evidence six years ago when they arrested Devonte and they don’t have the evidence now and they won’t be able to invent the evidence by the time the trial rolls around. This case needs to be dismissed. It’s a travesty of justice to both Devonte and Justin Gage.”

As he waits to learn what happens next, Gray will experience the holidays the same way he has since 2018 – worrying, haunted. He did laugh, however, when he told us his next therapy session is Friday. We asked if he felt himself slipping back into Survival Cyrus mode.

“I’m actively trying not to,” he replied. “But I really don’t know what’s to come.”

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.