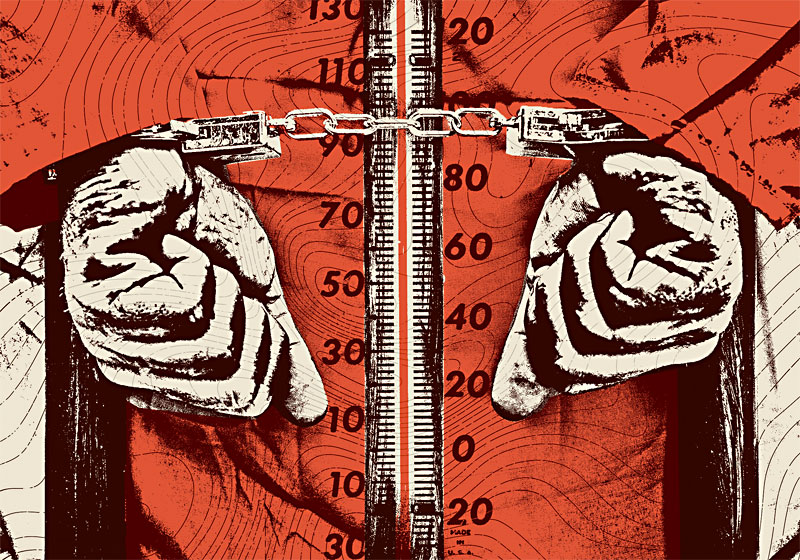

Texas Prisons Are Cooking People Alive. Are We Okay With That?

Part 1 in a series about heat in prison

By Brant Bingamon, Fri., Aug. 11, 2023

Alexis Woods is facing the same crisis as other prisoners across Texas in this summer's historic heat. With temperatures soaring to 120 and even 130 degrees in her cell at the Dr. Lane Murray Unit outside Waco, Woods' cot is too hot to sleep on. So the 26-year-old is sleeping on the floor.

"She will take a shower, then lay on the floor, go under her bed, pull the covers down, and put her fan right there," Alexis' mother, Samantha, told the Chronicle. "So it's like a little box that is bearable. But as it's gotten hotter and hotter, now the floor is hot, and the walls are hot. So she's just like, 'Mom, I don't know what to do.'"

We heard from over a dozen family members of incarcerated people in researching this article, as well as several former and current prisoners. They say this improvisation – drenching yourself and lying down on bare concrete to sleep – is a near-universal practice in cells without air conditioning. These cells, metal and concrete boxes that retain and amplify the heat of the day, are found in two-thirds of Texas prisons. They house approximately 95,000 people. Roughly 4 out of 10 are serving time for nonviolent offenses, according to stats from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

"And in an hour, when that water is completely evaporated, they're waking up and pouring more water onto the floor," said Marci Simmons, a former inmate at Lane Murray who now runs the advocacy group Lioness Justice Impacted Women's Alliance. "And some people don't have access to the shower. They have to use the sink in their cell. The water that comes out of the sink, it's warm, it's warm enough to melt instant coffee. But the water in the toilet, if you flush it several times, it gets cool. And you have people who scrub their toilet out and put toilet water on the floor, trying to get some relief."

Simmons told us that during her years at Lane Murray the summer routine was regularly punctuated by the arrival of ambulances, putting the prison on lockdown. She said she witnessed vomiting, seizures, and loss of consciousness each year – symptoms of heat cramps and heat stroke. Left untreated, heat stroke can progress to heat exhaustion, with the heartbeat elevating to dangerous levels as the body works frantically to cool itself. Death often comes from cardiac arrest.

TDCJ denies that there is widespread heat stroke or heat exhaustion in the prisons. A TDCJ spokesperson told the Chronicle that in the last year, 25 employees and only 9 inmates needed medical care beyond first aid for heat-related illness. But given that prisoners outnumber corrections officers roughly 7 to 1, we would expect to see at least 175 inmates with heat-related illness requiring medical care – and that estimate is probably too low, because it assumes that the rate of heat-related illness is the same for staff who go home at the end of their shift and prisoners who are in hot cells around the clock. (The TDCJ employs roughly 17,000 COs and houses 116,000 prisoners, per a spokesperson and TDCJ's 2022 statistical report.)

Samantha Woods says Alexis has repeatedly called her in tears this summer, describing fellow inmates collapsing and having seizures. "They're dropping like flies," Woods said. "And my daughter tells me, 'Mom, there are people in here that are too old. There are people that are mentally ill, that should be in another unit. There's people that have major medical issues, they're in wheelchairs, they're on walkers.' And with TDCJ, the narrative is so twisted. They say they have special units for the elderly. Well, I see them every single time I visit my daughter."

Joseph Martire has spent this summer at the Estelle Unit north of Huntsville, where five inmates have died since June. He said that Estelle, like Lane Murray, has many infirm inmates. "Of course there is fear," Martire told us. "You got a lot of people on this unit that have medical problems. The heat's a very big risk for them, exacerbating their health problems. They could get heat stroke or a heart attack, heat exhaustion. And you've got regular people that are susceptible too."

Martire himself has had difficulties. He says this summer has been the hottest in his 18 years behind bars. That includes last year, when he had a serious episode of heat stroke. "For 2½ hours his cellie and other people on the run were hollering, lighting fires, trying to get an officer to come down," Martire's wife, Kat Komisky, said. "When medical got to him, they said it was just in time. He had been unconscious and convulsing. Since then he's had more sensitivity to the heat. He's had multiple episodes with loss of consciousness, numbness and tingling throughout his body, seeing black spots in his vision."

“That’s a Bald-Faced Lie”

"Every summer the deaths and suicides increase – it's like clockwork," said Dr. Amite Dominick, the founder of Texas Prisons Community Advocates, which tracks inmate deaths. With this summer being so hot, Dominick has been deluged with pleas from inmates and their families. "Right now, the family members are terrified," she said. "They're panicking, honestly. It's well beyond, 'They're in prison and it's hot.' It's, 'Oh my God, they haven't called me – are they alive or dead?'"

According to the Texas Attorney General's Custodial Death Report, over 100 people have died in Texas prisons since the middle of June, when the heat began in earnest. A pair of recent studies by Texas A&M and Brown University estimate that as many as 12% of these deaths could be heat-related. But that's not something you will hear from TDCJ. According to the agency, there hasn't been a heat-related death in any Texas prison since 2011.

"When TDCJ insists that they haven't had a death from heat-related causes in 12 years, that's a bald-faced lie," said Tona Southards Naranjo, mother of Jon Anthony Southards, who died at the Estelle Unit on June 28. Naranjo said she viewed her son's body after his death and he had a heat rash "from the top of his head to the backs of his knees."

Naranjo told me that she spoke to her son three times the day he died. "He was complaining that it was so hot. 'Turn your fan on, baby,' I said. He said, 'I can't, Mama, it makes it hard for me to breathe.' I said, 'What about a cold shower?' He laughed at me and said, 'Mama, I haven't had a shower in four days.' My son was in solitary confinement. So he was dependent on the guards for respite.

"I believed with all my heart that he would be safe in TDCJ. I believed with all my heart that going to prison would save his life, that he was safer there than he was on the streets at the time. But what happened was a judge sentenced my son to 20 years, but the TDCJ sentenced him to death."

This is Part 1 of a three-part series on the dangerous heat in the two-thirds of state prisons that lack air conditioning. Read Part 2 here and Part 3 here.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.