DPS Director Steve McCraw Issues Immigration Marching Orders

DPS troopers "have an obligation" to work with ICE, Border Patrol

By Debbie Nathan, Fri., July 7, 2017

Just after lunch one day in late May, I received a phone call from a blocked number. That usually means a young-woman bot chirping about a free Caribbean cruise. I almost didn't pick up.

When I did, the voice on the other end was live and a little jumpy. "Are you the, um, the reporter or something?" the caller asked. "Doing an article, um, about DPS and the Border Patrol?" The person said they were with the Department of Public Safety, but would not provide a name.

As it happened, at the time I'd been sending emails for days to DPS's media department. My emails contain my unlisted phone number in the signature, and no one could have known it – or that I was sending the emails – unless they were with DPS. I'd been reporting on the agency's longstanding practice of stopping Latinos in South Texas for minor traffic infractions, then asking them about their immigration status and turning many in to the Border Patrol ("Snuffed Out," June 2). Particularly, I was inquiring as to why, in November 2016, some border counties had seen a sudden spike in such cases. Hidalgo County, including the city of McAllen, went from one referral in October to 35 in November. Just west, in Starr County, referrals jumped from one to 25. DPS had supplied this surprising data earlier this year to state Sen. José Rodríguez, D-El Paso.

For several years now in the Rio Grande Valley, trooper-initiated handovers have represented a primary method for Texans to be identified as undocumented – then detained and often deported. From Brownsville to Laredo, DPS squad cars buzz around minor traffic infractions like bees circling flowers. Troopers ask for a driver's license; if a motorist or passengers don't have one – in an area where 90-98% of the population is Latino, and as many as 15% are undocumented – the deportation machine kicks in.

I was reporting on that machine as a precursor to what may well happen if Senate Bill 4 goes into effect on Sept. 1. SB 4's intent is to crack down on illegal immigration. Nationally, it's the first signed law of its kind since Donald Trump took office. It establishes harsh penalties for police chiefs, sheriffs, and possibly even frontline law enforcement who fail to cooperate with federal immigration authorities, and allows police to ask about immigration status whenever they detain someone.

Like SB 4, DPS's presence on the border is deeply politicized – and includes a mandate that has diverted hundreds of troopers for the past few years from Texas' interior to the roads along the Rio Grande Valley. The stated purpose is to fight cartels and terrorists, but there's little evidence that this enforcement has done anything more than nab those who drive with broken taillights. Last November, it seemed, drivers had more to worry about than ever. Was that jump connected to Trump's election?

DPS's media department spent days stalling me for answers, notifying me regularly that they needed more time to research reasons for the spike. Then the whistleblower called, claiming they knew why the spike had happened.

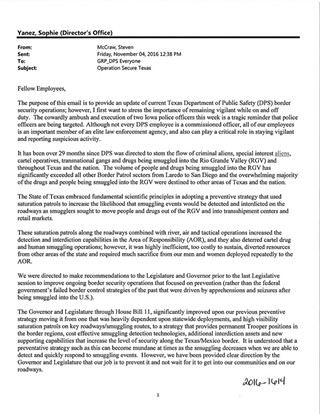

The caller told me that on Nov. 4, DPS Director Steve McCraw sent an email to the entire agency instructing that if troopers suspected someone of being undocumented, they were required to call the Border Patrol or ICE. Before that email, the tipster said, troopers had discretion about whether to call federal authorities. The new order, the caller said, with its lack of an option for discretion, constituted "a break from DPS history."

I immediately emailed Tom Vinger, DPS's head of media relations and the individual who'd been stonewalling me about the November spike. I asked him about an immigration-related directive from his boss, dated Nov. 4. It took Vinger two days to respond. Rather than verifying the email, he said he'd halted research into the "spike."

Another two days passed before, just prior to midnight on a Saturday, Vinger emailed to acknowledge that, indeed, DPS Director McCraw had sent an email about immigration enforcement. The email's contents described "nothing new," he wrote. "DPS does not enforce immigration laws .... However, when our state law enforcement officers make contact with someone (during a lawful encounter) who is admittedly or suspected to be in the country illegally, that individual is immediately referred to the appropriate federal authorities."

I've interviewed many immigrants in the Rio Grande Valley who were stopped before November by troopers for traffic infractions – and even though they were undocumented, the trooper, after hearing about their years living in Texas, their steady jobs, and U.S.-born kids, would let them go with just a ticket or a warning. Until that November spike, many troopers used discretion. In his response to me, Vinger did not acknowledge what the whistleblower had claimed: that troopers were now being ordered to do handovers. I asked Vinger for a copy of McCraw's memo, but he did not comply, so I filed an open-records request. Two weeks later, I got the email.

The email encourages troopers to harbor globalized suspicion. "It is not possible," McCraw writes, "to look at someone and determine whether they are a criminal alien fugitive, cartel operative, special interest alien, transnational gang member or smuggler/trafficker. When probable cause exists that someone illegally crossed the border ... we have an obligation to refer those incidents to the U.S. Border Patrol, or ... Immigration and Customs Enforcement."

We have an obligation.

At 2:30 in the afternoon on Nov. 4 last year – the day the DPS directive went out – a trooper near the little border town of Roma stopped a Hispanic-surnamed man on Farm to Market Road 650. The man was not even driving. His violation? On a remote country byway featuring little but scrub trees, livestock, and caliche, he was walking in a place without a sidewalk.

Last week, a phalanx of attorneys descended on the federal courthouse in San Antonio. Most were representing Texas cities and counties, including Austin and Travis County. All are suing to have SB 4 declared unconstitutional. ACLU attorney Lee Gelernt told Judge Orlando Garcia that the feds have long ordered that no local agency can prevent other agencies from sharing information with the Border Patrol and ICE. But by the same token, the feds cannot make such sharing obligatory. It's optional.

Jose Garza, on behalf of El Paso County, explained to the Chronicle why DPS and McCraw are being sued even though neither directly created SB 4 or signed the bill. "DPS resources for former, everyday enforcement are being shifted to federalized immigration enforcement, which is harming border communities and is a precursor to what will happen under SB 4," Garza said. The agency and its director were added to the lawsuit "as a backdrop, a framework," for showing the court the destructive effects of the SB 4-style enforcement that already exists.

Today, many Texas municipalities prohibit local law enforcement from asking people about their immigration status. They do so mainly to ensure that crime victims and witnesses will feel comfortable dealing with police. But if SB 4 goes into effect, cops and sheriff's deputies will be able to ask with impunity, then contact Border Patrol and ICE – and share not only the immigrants' information, but the immigrants themselves.

In San Antonio, a lawyer from the state attorney general's office who was arguing in favor of SB 4 downplayed repercussions when Judge Garcia posed a hypothetical: What if a cop gathered information about someone being undocumented, but decided not to pass that information to the Border Patrol or ICE? What would happen then?

"Nothing," said the state's attorney.

For DPS troopers, thanks to McCraw's Nov. 4 email, "nothing" is no longer an option. SB 4 may not yet be in effect, but troopers already have an "obligation" to turn in immigrant Texans.

Debbie Nathan freelanced this piece and is also an investigative reporter with ACLU of Texas.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.