The Future of Health Care?

Dell and Central Health “re-think” the way we provide – and pay for – health care

By Michael King, Fri., March 24, 2017

Early one recent Monday morning, in a basement clinic at University Medical Center Brackenridge, a half-dozen doctors and assistants huddled around computer screens reviewing patient records and X-rays. For roughly an hour, they skimmed through patient records, considering both the monochrome images on the screen – knees, pelvises, a few ankles in various states of damage or disrepair – and a collection of printed reports on the patients' overall physical and emotional health. Most of the latter were derived from prior questionnaires answered by the patients, online or in telephone interviews.

The records covered patients scheduled for clinic appointments that Monday, although team leader and medical director Dr. Karl Koenig readily acknowledged that not all of the patients – many of whom are poor and don't go to the doctor "until they absolutely have to" – would arrive. "Some days we can have 20-to-25 percent no-shows," Koenig said. "Either they can't get a ride, or something comes up in the family, or – occasionally – they're just too depressed or overwhelmed to keep their appointments.

"Some days," he continued with a smile, "they pretty much all turn up. Then we have a very busy day."

Koenig and his team form one of Dell Medical School's new "integrated practice units": a group of medical specialists assembled to work together and to treat the "whole patient" – in this case, not just those knees and hips showing years of wear and tear (or worse) in the X-rays, but the body and mind surrounding the broken joints. Koenig points to an X-ray showing a badly damaged and badly healed pelvic injury that has for years affected the patient's ability to walk. "He thought he had a broken leg, but he had no money to pay a doctor, so he just waited until he could manage to get around. His condition has slowly gotten worse, but surgery after so many years is not a likely option. Now, we need to determine what we can do to make his life better."

One after another, the X-rays reveal their secrets to the group of doctors and assistants; they consult each other on today's appointments, what they need to learn from their patients, and which procedures – from reassurance, to mental health referrals, to medication, all the way to a recommendation of surgery – might "make their lives better."

That's not the sort of group approach one usually hears from specialists, particularly orthopedic surgeons – they're accustomed to "fixing what's broke," the made-visible wounds of bones and joints. Often their sometimes impatient patients presume that the entire purpose of the X-rays and the office examinations is to identify accurately the visible, fixable problem, and get on with the cutting and sewing.

Another surgeon, Dr. David Ring (also Dell associate dean of Comprehensive Care), recalled one of his initial smartphone-aided teleconferences with a patient who had waited too long for an appointment to examine her injured wrist, and was skeptical that a highly paid surgeon was serious about being interested in her situation. "She was angry about the delay, and worried about her injury and whether it would prevent her from her own work as a nurse assistant," said Ring. "Eventually, after we talked for a while, she apologized and told me that when she came in to see me, she would give me a hug.

"Sure enough, when she arrived for her appointment, she gave me a hug, and made it clear that we had established a sense of trust. More important, she made her own decision, based on the examination and what I told her about her wrist, that surgery wasn't necessary and the problem should resolve itself on its own. That was only possible because I had the time and circumstances to establish a relationship with her – and no institutional pressure to 'do something' to justify a bill."

As things stand now, say Ring and his colleagues, structural and financial incentives built into the practice of medicine generally reinforce conventional doctor and patient expectations. A nationally institutionalized "fee-for-service" model, underwritten by insurance companies and government programs, pays doctors for "doing things": ordering tests, utilizing expensive equipment, performing surgeries.

Koenig, his team, Dell Medical School Dean Clay Johnston, and the entire Medical School faculty and staff insist they're determined to change all that, from the front end of the clinic interview to the back end of the financial payment structure. They say they're determined to build the new medical school – the first such from-the-ground-up project in the U.S. in roughly 50 years – on the "value-based" health care model, treating patients and rewarding doctors on the basis of actual "outcomes" – how healthy they keep their patients, and ultimately, how healthy they keep whole populations in Central Texas.

"It is about transforming health care," reiterates Johnston, with the frank intention to "spread that across the country." A new medical school, he believes, not already tied to a standard fee-for-service business model and conventional contracts, is the "perfect place" to initiate such a transformation. The school is developing new relationships, under which doctors get paid not for more procedures – instead, they are paid when people are "healthier, pain-free, and productive."

"We want the emphasis to be on 'health' rather than 'care,'" Johnston reiterated. "We want to be judged on the basis of how healthy we can keep the population of Travis County."

A Pipeline of Doctors

When Patricia Young Brown stepped down last year after 12 years of leadership at Central Health, she wasn't exactly retiring. She's been simultaneously enrolled in seminary school for the last couple of years, with her studies focused on end-of-life issues and counseling, a fulfilling although not exactly stress-free second vocation. But her decision to move on is in keeping with her tenure at the health care district, and her conviction – as she watches the Dell Medical School rise along the Red River edge of the UT-Austin campus – that she has accomplished what she set out to do when she took on the Central Health job in 2005.

"The Austin history has been different than that of other major cities in Texas," Young Brown told the Chronicle in a December interview. "Because we had Brackenridge Hospital addressing indigent care for so many years, we didn't have the other health care infrastructure, like a health care district, to rely upon. But over the years, as the city grew and the health care landscape changed, we began to realize that Brack alone was insufficient, and that we couldn't supply a sufficient level of care – especially specialist care – that the growing population required. And once we organized Central Health, we also began to realize that we couldn't simply hire enough specialists to address the shortage – how do you buy something that isn't there? We had to create our own pipeline of doctors. And that's how the notion of a new medical school began to take shape."

There had been talk of an Austin-based medical school for years, mostly as a dream of various University of Texas administrations as well as some public officials and health care advocates, but other priorities had taken precedence, and the project had never quite caught fire. The idea needed a prominent champion, who arrived in the form of state Sen. Kirk Watson, the former mayor known for his relentless cheer and boundless energy. With a "10 goals in 10 years" plan that primarily emphasized health care, Watson lit the fire under the Medical School campaign, getting it on the Travis County ballot in 2012 in the form of a property tax increase for Central Health. The additional funding would have a dual purpose: establishing and funding (jointly with the university, underwriting the physical plant) a new medical school, and to focus that school (and leveraged Medicaid funding) on health care for the underserved.

There was some organized public opposition – less to the idea of the school, than the requirement to pay for it – and some more generalized objections to the continuing expansion of UT-Austin. But energetically driven by Watson, the proposition was supported by a broad cross-section of Austin organizations, and passed handily, 55-45%.

A few weeks before the vote, Young Brown told the Statesman's Mary Ann Roser: "What residents are paying for is health care delivery to the community. We're not building buildings. What we're proposing to do is pay for care through Medical School faculty, [medical] residents and medical students. We're also trying to leverage an amazing opportunity we have been presented ... [with the Medicaid] 1115 transformational waiver to essentially support this new delivery system, the expansion of services and the creation of a new teaching hospital and new medical school. All of these bring more services to our community."

Acronyms Under Construction

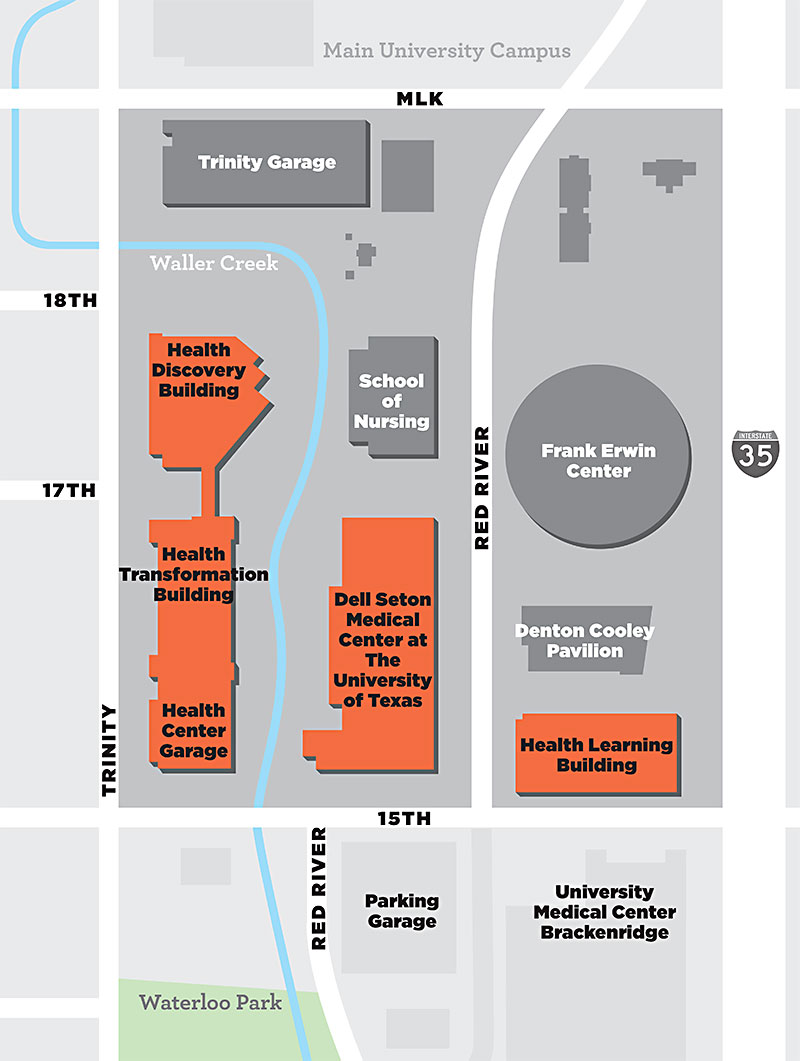

With the Medical School complex still rising along a now dog-legged Red River Street, it's still too early to confirm that the promise has been fulfilled. While the main teaching facility (the "Health Learning Building") is completed and in full use (the first class of 50 students began classes last June), the "Health Discovery Building" (medical research site) and "Health Transformation Building" (surgery and clinical site) – are still under construction, scheduled to be completed this year. ("They'll all be acronyms in no time," laughs one of the orthopedic team.) That doesn't even count the new teaching hospital – the Dell Seton Medical Center at the University of Texas – around which the Medical School has been built. The hospital is scheduled to open in May, to replace the aging and obsolete Brackenridge and to become the central teaching hospital for the whole complex.

In the meantime, that substantial work still in progress has required makeshift arrangements. The orthopedic clinic is operating in the UMC Brackenridge basement, space rented by Dell from Seton, functional but not ideal for the orthopedists and their patients. Koenig says the new "Transformation" clinic is being designed with the new approach in mind – e.g., couches instead of office chairs for meeting patients, and updated equipment to better utilize doctor-patient interaction and digitally collate all relevant patient records, instead of the mixed digital-and-paper files they're working with now.

They already employ now-ubiquitous high-tech tools that were not yet available only a few years ago. "We found that smartphones are nearly everywhere now, and even many of our poor patients have them," said Dr. Ring. "Sometimes patients just can't get here," he continued. "I do a lot of direct calling. Sometimes they're surprised to see me on the smartphone – it can be almost like a house call."

Ring, who moved to Dell from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, is enthusiastic – not only about the technical innovations, but the structural and financial changes promised by the Dell model. "In a fee-for-service model, the emphasis is on volume – you just don't get that opportunity to build relationships with patients, with the whole person." Speaking not only of his own new practice, but that of his colleagues, he says: "We've been waiting all our lives to do that."

Liberating Practitioners

From the dean's office down to the working clinics, there's a common refrain echoing Johnston's emphasis on "healthy outcomes" for patients rather than multiplying opportunities and obligations for "care." "As things are structured now, the financial incentives are structured for practitioners to 'do more,'" said Johnston. "Our goal is to learn how to do this better." Johnston said that not only is "doing more" seldom the best model for patients, it also generates "a tremendous amount of waste," in the form of unnecessary tests, unnecessary procedures, and too many poor patient outcomes.

Johnston is aware that the "fee-for-service" model he's describing remains the standard model for most health care and health insurance in the U.S., and says he is under no illusions that changing that situation will be anything other than an uphill journey. He said his previous experience – at the University of California-San Francisco School of Medicine – convinced him that even at the best institutions ("and UCSF is a really great place"), the established structures make change very difficult. "What we're trying to do here [at Dell Medical] is to collect innovative thought leaders who are themselves determined to do things differently. That's liberating for the kind of person we've been recruiting." He believes the opportunity to build a new model from the ground up has attracted faculty, staff, and doctors who have the same ambition, along with the dedication to use that model to serve the broad Central Texas population.

Johnston and others point to the theoretical work of Elizabeth Teisberg and Martin Harris, developing the Med School's "value-based" approach to health care systems: finding ways to produce and quantify better outcomes for patients. Teisberg is the author (with Michael Porter) of Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results (2006), a seminal work in the field, arguing that the profession and the industry must shift from the fee-for-service model that currently governs medical practice, hospital finances, and health insurance plans, to a value-based structure that measures and rewards health outcomes – and over time, by eliminating unnecessary and repetitive treatments, broadly reduces the cost of care. Teisberg, now a full professor and executive director of Dell's Value Institute for Health and Care, and colleague Scott Wallace summarize their approach in a recent article, "Four Steps Within Your Stride" (www.healthmanagement.org): measure outcomes; document "care paths" to determine best practices; use integrated teams of varied expertise across the patient's full cycle of care; design solutions that incorporate the direct experience of patients. Elsewhere, Teisberg summarizes the value-based goals: "Higher value opens the opportunity to enable better health for more people with the same resources."

The Whole Life

"Value-based health care" is no longer a new idea – insurance companies as well as hospitals and practitioners are beginning to explore the approach, as is Medicare – but it also hasn't been around long enough to answer the question of how it will work in actual practice. Thus far, the Koenig orthopedic group has been Dell's most visible effort to give a reality to "integrated practice units," and the early results have been remarkable. Specialist orthopedic care was initially identified as a problem area for Travis County patients, particularly underserved (and often uninsured) patients from poorer neighborhoods. By prioritizing the severest cases and working with existing CommUnityCare clinics and other doctors on spreading the work, the wait time for specialist care has been cut from more than a year to less than a month. That is, patients are receiving orthopedic appointments in a standard three weeks or less.

Meanwhile, a similar focus was placed on improving health care for women – especially the uninsured and poorer women who are the prime responsibility of Central Health. Dr. Amy Young, chair of the Department of Women's Health, said that when she arrived at Dell in 2015 (most recently from the LSU Health Sciences Center in New Orleans), what drew her was the possibility of "rethinking how all this really works, in a meaningful way, instead of just fixing immediate problems." In her experience, women's health care too often "gets subjugated to just prenatal health," and the aim of her department and her own gynecological and obstetrics practice is to consider women's care "across the whole life of a woman."

Beginning in January of 2015, Young joined a group working through a Community Care Collaborative (a Central Health initiative) to "integrate care between the inpatient and outpatient system. We're providing a higher level of care upfront, and offer similar resources to insured and uninsured patients." Young says much of the early focus was on integrating care among hospital facilities and clinical sites, with a goal in part of enabling doctors to "see patients in their community rather than in the hospital."

The work took substantial shape in the spring of 2016. "We've found that leads to better outcomes, and better follow-up care. We're still gathering numbers, but anecdotally, it appears that patients are returning more regularly to the clinics after delivery, and more consistently adopting contraceptive plans, postpartum." Young says integrating the hospital and clinic care provides the medical residents better understanding of the community context where their patients live, and that in turns delivers better ongoing care. It also means better access and provision of care "beyond the perinatal." She cites another project focusing on cervical cancer, and notes that the Medical School context has enabled her to collaborate with other department chairs, to provide an "interdepartmental and interdisciplinary approach" to cancer treatment.

From her prior experience in Louisiana and Houston, Young is quite aware of the particular health care challenges in the South, where the political climate – often indifferent if not hostile to reproductive health care, less Medicaid availability, etc. – can present additional obstacles. "The political challenges tend to make the overall system more fragmented, and the treatment decisions more complicated," she says. "It's not simple, and can make the work more difficult. But the [medical] residents are very aware of the issues involved – and sometimes, better training occurs because of the necessity of balance."

Young emphasizes that the "rethinking and redesign" work of her department and the Medical School are "completely geared to the underserved population. We are training our residents and moving them into a community where they'll have to address the social determinants of health, and treat the patients in their own environment."

A Healthy Population

The women's health projects and the orthopedic care redesign both represent specific examples of Central Health and Dell's dual intention to "redesign health care" and to implement that redesign in treatment for the health care district's target population: primarily the uninsured, underserved, and indigent population of Central Texas. Right now, these two are the most visible of Dell's programs – but they have been developed within a much larger and more ambitious project, under the shorthand designation of "Population Health."

Earlier this year, Dr. William Tierney, chair of the Department of Population Health, told a Carver Library audience that the "service mission" of his department is to become "a catalyst to improve the health of the community." Tierney says that while other medical schools have developed Population Health departments, their aims have been research-only. Dell's, he says, is the first such department whose primary project is improving the health of an entire community. In a post last year on the Medical School's website, he further defined the departmental mission: "to enhance the health and well-being of the residents of Austin, Travis County, and Central Texas, with an emphasis on vulnerable persons and those suffering from health disparities." He said his department, in collaboration with other local health care providers, is already engaged in "household-level assessments of every household served by Central Health in Travis County" (some 200,000 people in all), many of whom live in the Eastern Crescent. Tierney has prior experience in Indiana and Africa (Kenya) at developing community-based methods of assessing and improving population health, and he notes that the process requires engaging the community and local organizations in defining, measuring, and addressing the issues identified.

Another Population Health community engagement project is the "Center for Place-Based Initiatives." Lourdes Rodríguez, director of the Center, cheerfully describes the "really wonky" name as emphasizing how "place matters" in marshaling "local resources to solve local problems." Originally trained at the University of Puerto Rico as a chemical engineer and microbiologist, Rodríguez eventually moved into public health, but bringing an engineer's focus on "solving problems." She spent the last 13 years in a New York City program designed to build community collaboration on public health issues.

Rodríguez uses a "potluck dinner" metaphor for that project and in describing the approach of the Center; it reaches out to local residents to bring their "best ideas to the table" for health care solutions, with the Center then acting as a "matchmaker" between the ideas and methods, and partners for implementation or development. Facilitated through a "Community Strategy Team" that includes local advocates and activists, the Center has been compiling dozens of submitted ideas after public outreach, and sorting them into what Rodríguez calls three "buckets" for further analysis or action.

"Some we will find impractical, or at least impractical with currently available resources; others we'll say, 'We can't support these directly, but we'll suggest other partners that might help to pursue them'; and in a third category, we've identified about a dozen ideas that we want to try and test here, in projects running 3 to 12 months – we don't want to delay them – and see how they work."

"The overall goal is to design place-based initiatives to improve and practice public health," Rodríguez summarizes. "Sometimes that means 'looking upstream' to the causes of chronic diseases – causes that are often social conditions." Rodríguez cites the example of asthma, which is often a consequence of a family's living circumstances; as another example, she notes the limited availability in the Austin area of public transportation, which can contribute to the inability of poor residents to get access to care. Her strongest emphasis is on community collaboration: "Population Health is about everybody chipping in."

Building Connections

Maninder "Mini" Kahlon, Dell's vice dean for strategy and partnerships, is a whirlwind of big-picture conversation about how all these Dell programs fit together in the very large project of transforming the "ecosystem of health care" in Central Texas – from prevention at the front end to finances at the other. Wearing her "strategy" hat, she reiterates the school's primary goal of changing the structural emphasis from "care" to "health." She recites a list of the school's partners that fit into that project in various ways: Central Health, the Seton Healthcare Family, and UT-Austin, of course, but also CommUnityCare clinics and other providers that are steadily forming collaboratives with the Medical School. She points again to the orthopedic integrated practice unit and perinatal care project as signature initiatives that will be expanded and replicated, with a continuing emphasis on keeping people healthy.

Kahlon's institutional attention is also occupied with the connection between health care systems and cost: "We want to improve outcomes at lower costs." One problem, she says, is that the Travis County health care system is "very segregated" in institutional terms; she spends a lot of her time making connections between various providers and organizations, encouraging them to work together and with the Medical School. Collaboration, she says, will mean both better outcomes for patients and lower costs for providers and insurers – who still need to be fully persuaded that paying for outcomes rather than procedures will eventually reduce overall costs. One advantage in Travis County, Kahlon says, is that several major local employers – Austin ISD, the UT System, the City of Austin, Dell Inc. – are directly interested in the school's proposals, self-fund their own insurance coverage, and have begun to see the advantages of a value-based system.

Like Johnston, Kahlon also came from UCSF – "They call us 'The Crew From San Francisco'" – and says she knows the tensions and responsibilities in working for and with major public institutions. In Austin, she's become aware of some persistent public suspicion of UT-Austin's role in the community, and the potential sense that UT and the Medical School will inevitably value empire-building over community health care, especially for those most in need. "If we don't address the community's needs," she insists, "we will fail. And the only way we can address those needs, is by becoming part of the fabric of the community."

The Mission: Health

Down at the orthopedic clinic in the Brack basement, Dean Johnston's grand goals are in the air, but only implicit in the clinical conversations. Patient John Seger cheerfully confesses that he "used up his body" playing football and riding stunt motorcycles, and that his hip joints – replaced 11 and 15 years ago – will soon need to be replaced again. He says he's very grateful for the care he's received from the Dell doctors, at a minimal cost he can afford. He's 53 years old, he says: "It's not the years, but the miles."

In an adjoining ex-amination room, Dr. Devin Williams examines Irabel Avila's arthritic knee; José Avila translates for his father, who's worried that the knee seems unstable. (He's been referred here by the People's Community Clinic.) "There's no cure for arthritis," says Williams. "If somebody invents one, they'll be rich." He recommends continued physical therapy, and after he watches Avila walk, "We should be able to find a brace for that wobble."

Do the handful of patients meeting with Williams and the other doctors, moving briskly through the clinic on one Monday morning, signify a new, better future for health care, in Central Texas and beyond? It's too soon to tell. It is clear that Dean Johnston, the Medical School teams and faculty, and the supporting staff, all firmly believe in the transformative mission they've assumed, in establishing the school, and in accepting responsibility for the health of the Central Texas community.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.