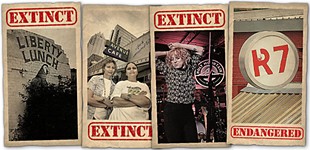

About That History? It's Gone.

Developers destroy a little bit more of Eastside history

By Cindy Widner, Fri., May 4, 2012

The littered lots at 2019 and 2021 E. Fifth Street have much to recommend them as an office site. Bordered by industrial warehouses – including the Pure Castings factory, controversial for its fumes and proximity to Zavala Elementary (see "Cast Away," Aug. 28, 2009) – the properties look out on railroad tracks and the backside of an ungainly apartment complex. Despite the ruthless advance of hipster bars in that direction, the stretch of Fifth from Chicon to Robert Martinez Jr. streets is a bleached-out landscape of weeds, asphalt, and windowless industrial buildings. It feels isolated from the vibrant neighborhoods only a few blocks away and, at least in its current state, doesn't telegraph as a prime spot for retail or residential development – affordable or otherwise.

When the East Cesar Chavez Neighborhood Planning Team and other nearby neighborhood groups saw stirrings of new activity on the long-fallow property now being developed by Endeavor Real Estate Group, they weren't overly concerned with the office building that Endeavor principal Will Marsh says is planned for that space. Rather, they wanted to know what was going to happen to several historic buildings – particularly three wooden residential structures – that had sat unoccupied on the property for years.

With the help of neighborhood historian Danny Camacho and resident architects, Amy Thompson, chair of the East Cesar Chavez Neighborhood Planning Team's historic preservation committee, had concluded that the structures were worth saving. "They were very unique structures," she said. "They were completely architecturally sound." She had been working for two years to get them preserved and, if necessary, relocated.

Instead, in early March, all but one were abruptly "made into toothpicks," according to Thompson. No attempt was made to salvage the houses' longleaf pine, she said, and "architectural details were lost, workmanship was lost, the cabinetry, the doors, the shiplap, the beadboard, sash windows that people pay hundreds of dollars for. It was a huge waste of resources."

The city's Code Compliance office and Historic Preservation Officer Steve Sadowsky were alerted. Big Red Dog Engineering, the company in charge of the project permits, had failed to obtain demolition permits, so the city issued a stop-work order while the company filed them belatedly.

Thompson began working with Council Member Mike Martinez and the city to find resources to relocate the remaining house to the neighborhood's community garden. As a backup plan, she and her domestic partner, Cesar Sylva, took out a second lien on their home so they could move the house to their large yard a few streets away. Marsh assured Thompson via email that Endeavor would not "touch the house you are interested in without discussing with you first."

Yet without a word or a note, the house was demolished on April 6. Marsh said the contractor, M & Jo Abatement & Demolition, had been told repeatedly not to touch the house. Mario Martinez, M & Jo's owner, said he had sent workers to clean up the lot and that they took it upon themselves to demo the building.

The case is currently under investigation, but Endeavor is probably not quaking in its loafers about a possible citation. Penalties are limited by state law and top out at $2,000 per incident – small change in most construction budgets and hardly a deterrent. Andrew Moore, council aide to Martinez, compared the problem to that of the Heritage Tree Ordinance. "We hear a lot of 'Oh, my contractor cut down that tree without a permit; it's a heritage tree, sorry.' And the fines are similarly low." He suggests implementing penalties the city could enforce, such as denying the offending contractor additional permits for a long period. "We would be able to say, 'All right, so you're on the bad list for 18 months to two years. Is that worth it to you?'" said Moore.

Sadowsky also said stricter penalties are warranted: "If we wouldn't allow a building permit on that site for a period of years or would deny the demolition contractors license to do business – if we beef up our penalties, we'll show anybody: 'Hey, you do this, it's really going to cost you. You're not going to be able to just write a check for this.'"

In the meantime, said Moore: "All over town, with redevelopment and especially on the Eastside, with certain structures, we need to try and protect the cultural heritage, the cultural feel, the backgrounds of the neighborhoods. We're losing a lot of those through redevelopment."

"As a community, we don't take our own history seriously, and that is a huge mistake," Thompson concluded. "Healthy individuals reflect on their personal histories, preserve what is valuable, and work to improve weaknesses. Healthy communities do the same. To date, Austin has not been proactive in taking stock of its own history."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.