Shadows Over Bergstrom

The new reality puts the squeeze on our 'Austin-style' airport

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., Jan. 24, 2003

You can get your chicken and biscuits at Popeye's on the way to the airport (there's one on Airport Boulevard, another on East Seventh), but you can't get 'em at the airport. Yet. Harlon Brooks of Harlon's Bar-B-Q, which operates three concessions at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport, would like to turn one of his spaces into a Popeye's franchise -- down at the forlorn east end (the low-numbered gates) of the Barbara Jordan Terminal, far from the Southwest, American, and Continental gates that carry the bulk of Bergstrom traffic.

On the other side of the terminal are the local brand names -- Schlotzsky's, Amy's Ice Creams, Matt's El Rancho, the Salt Lick -- that Austin is so proud to feature for the weary traveler. Right now, nobody is making big money at Bergstrom -- the concessions or the airlines or the city itself -- but the east side concessions are feeling the sharpest pinch. Hence Harlon's desire to bring in a national brand with its attendant marketing power.

In any other city in America, the conversion of a single airport restaurant from one kind of fast food to another would be, to put it charitably, a nonevent. But Bergstrom is different. The Popeye's plan is on hold because members of the City Council -- particularly Jackie Goodman and Daryl Slusher -- need further convincing that the city's commitment to "local flavor" at Bergstrom will not be compromised. "I think the absence of chains and [presence of] local businesses in the airport is one of the great attractions of our airport," Slusher noted from the dais. "It's won a lot of praise from a lot of people, and we've worked hard to get it like that in the first place." He and Goodman asked staff to explore other ways to drive more traffic to the east end before moving forward with the Popeye's plan.

The Chicken Fight is mostly symbolic, since the Popeye's franchise would actually be locally owned. (And ironically, despite their local branding, Schlotzsky's, et al., are mostly operated by a national concessionaire, CA One Services.) But the chicken controversy symbolizes the very real challenges facing Bergstrom across the board. On the one hand, Bergstrom is different: the local businesses, the live music, and ample public art, the local recordings instead of Muzak and local TV news instead of CNN, the state-of-the-art tech facilities, the natural light and wide-open spaces, and the lack of garish primary colors. Last fall, a J.D. Power customer-satisfaction survey named Bergstrom America's favorite airport, and its strategies -- at least before 9/11 -- were being copied by other cities around the country.

On the other hand, everything else is different now, too, and local flavor isn't as high a priority as it used to be. So the city's Dept. of Aviation has a challenging mission. It must maintain Bergstrom's cherished identity as Not Your Average Airport. It must accommodate the sizable new federal security apparatus inserted hastily and bluntly after September 11. It must support the airlines as they skirt bankruptcy and watch the business-travel market collapse. It must shore up local revenues that are down one-third since the airport's peak. And it must plan for future Bergstrom expansions to serve a city and region that keeps growing even as its wealth is shrinking. After 18 months of near-constant change, the future flight plan for Bergstrom is still, well, up in the air.

Financial Turbulence

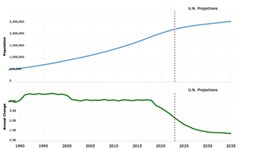

Even had September 11, 2001, been no more exciting than Sept. 10, Bergstrom today would be a different place than it was in its first two years of operation. "The airline industry was going into the tank because the economy destroyed business travel six months before 9/11," says city Aviation Director Jim Smith. Since then things have not improved. From January to November 2002, Bergstrom serviced 6.14 million passengers -- down 8% from the same time frame in 2001, which in turn had been down 6% from 2000; traffic has now fallen to the levels seen at Robert Mueller Municipal Airport before Bergstrom opened in 1999. Bergstrom made nearly $14 million in net profit for fiscal 2001 -- which ended Sept. 30 -- and expected to make more than $18 million in fiscal 2002. It made about half that.

That profit is banked by the city in the Airport Capital Fund, which is designed to underwrite future expansions. Last month, Smith's department released its ABIA Master Plan Update, which charts the intended course of those expansions -- all the way up to a new southern terminal, nearly the size of today's Barbara Jordan Terminal (which would itself become quite a bit larger), along with a host of other new and enhanced facilities (see p.24 for details). The total build-out of this program is conservatively estimated to cost $2 billion, three-fourths of which would be borne by the city; at its post-9/11 growth rate, the Capital Fund would be hard-pressed to underwrite the bonds this would require.

But according to the plan, Bergstrom expansion will not need to happen until the airport reaches 11 million annual passengers, "which we estimate is about five years away," says Smith. "Which means we should start planning to build more gates" -- six more at Barbara Jordan in the plan's first phase -- "since there's a five-year turnaround for that.

"After 9/11 and the turmoil in the airline industry," Smith continues, "it obviously gives us more time before we hit 11 million passengers. Which is a good thing. We could use a little more time. The airport doesn't have a whole lot of cash, and the airlines don't want their charges to go any higher. So 9/11 gave us some breathing room."

Of the money Bergstrom makes, less than half comes from the airlines -- the rest comes from parking (the biggest single item, where the airport took almost all of its 2002 budget hit), concessions, rental cars, and the like. "The stuff that can be related to the airlines gets charged to the airlines, and they agree to pick up the tab," Smith says. "We can't charge them any more than it costs to provide the service." Because Bergstrom is new and is still carrying a relatively heavy debt-service load, about $20 million a year, the cost per passenger to the airlines is higher than at other airports -- about $7.80 (today), according to Smith, compared to $3.09 in San Antonio (in 2001) and $2.51 at Dallas-Fort Worth. (These per-capita figures have, of course, gone up since then, since traffic has gone down. Costs at America's other big new airport, Denver International, now top $15, which adds to the woes of DIA's major carrier, bankrupt United Airlines.)

Obviously, a plane ticket out of Austin costs more than $7.80. "Airport costs are only about 4% of an airline's expense," he notes, "so the cost difference between us and a cheaper airport isn't going to make or break an airline. But [the airlines] are nonetheless aggressive" about containing costs and negotiating their deals with Bergstrom. (Or, as Smith -- a longtime Austin assistant city manager before taking over the airport in 2001 -- told the City Council during last summer's budget hearings, "You guys are a bunch of weenies compared to what we go through with the airlines.")

"When this airport was being built, the airlines put enough pressure on the city to reduce the size of the terminal -- by about 10 feet in major passageways," Smith continues. "Now, though, we're in a mode of building an addition to the terminal to house the security operation and equipment, which we wouldn't have had to do" if the city had built the Barbara Jordan Terminal to its original size. "But you have to negotiate. The airlines are a community's business partner, since you wouldn't have an airport without them."

The TSA Invasion

As Smith notes, there's a reason those big baggage-screening machines are now sitting in the lobby -- there's no room for them anywhere else. "The ideal configuration would be to have the machines in line with the existing [baggage handling] belt system," says Doug Johnson, Austin spokesperson for the U.S. Transportation Security Administration. "That's the ideal solution; that's in the planning stages, but nothing definitive yet." Smith says that "if it moves as quickly as possible, it'll still be 18 months to two years" before the TSA can have a proper home at Bergstrom. All estimates of how much it will cost to do this retrofit are speculative. But it will be a lot.

So far, despite all its talk about homeland defense, the Bush administration has not committed new funds to help local airports accommodate security-related costs (one of several line items on which states and cities are still waiting for promised federal aid). Federal funds have instead been diverted from grants intended to support other airport improvements, and it's unlikely D.C. will come up with funding for anything but capital costs, like the ground-level expansion of the terminal to hold the screening machines (which themselves cost $1 million each).

New TSA rules also add to operational costs; for fiscal 2003 the airport has budgeted an additional $1.6 million for security, including hiring additional airport police as required by the TSA, which is still grappling in D.C. over whether to create its own law-enforcement positions. Right now, the agency has only assumed the tasks formerly performed by private security firms under contract to the airlines (and the TSA is charging back some of that cost, about 40% of its overall budget, to the airlines). The cost-conscious agency is even asking the equally cost-conscious airlines to provide the staff to carry the screened bags from the machines to the baggage belts.

And, of course, the TSA's procedures -- specifically, the requirement that only passengers can go through security to the concourse -- have cut into the revenue earned from parking and from concessionaires like Harlon's. Still, the actual decline in passenger volume has probably done more to harm concession business than the TSA rules. Smith notes that, both nationally and at Bergstrom, only a tiny fraction of concession sales come from locations on the public side of the checkpoint. "It's actually worse since 9/11, since people now are in a hurry to get through security and then relax. We asked some of the vendors to experiment with carts in the pre-screening area, and they didn't do well at all." Even before the TSA machines showed up, the airport had abandoned plans to put more vendors in the lobby; right now, only one shop -- operated by Harlon's -- is before the checkpoint.

The TSA "is a third wheel" in the formerly binary relationship between airports and airlines, Smith says. "They declare what the procedure will be and who will do what. It's left up to the airport to determine how to pay for it. There's bound to be a lot of back-and-forth over time about who pays for security. Right now, everyone's still getting the ball rolling." There's also been plenty of back-and-forth in D.C., within the TSA and the Dept. of Transportation and the administration and Congress. The 15-month-old agency is already on its second director.

In Austin, under the direction of 20-year Texas Dept. of Public Safety veteran Mike Scott, the TSA seems to have done a better-than-par job of building a partnership with Bergstrom's team. "We couldn't ask for a better relationship," says Johnson, particularly with the airport police under former APD Deputy Chief Bruce Mills. "It's a fantastic relationship." The TSA's own employees are also -- by the agency itself -- regarded as a cut above their predecessors from Argenbright Services and later Wackenhut who had been contracted by Southwest Airlines (as Bergstrom's largest carrier) to provide security pre-9/11. Over Labor Day weekend, when the TSA first took charge of the checkpoints, Scott proudly announced that none of his employees were former screeners. Today, some are former Argenbright and Wackenhut workers "who applied and passed the test but that would not be a majority of them," says Johnson. "They've basically come from everywhere -- a cross section of smart people who wanted to do this."

One frequent traveler who's been watching the TSA invasion with a more-than-passing interest is UT architecture professor and Page Southerland Page principal Larry Speck -- who designed the Barbara Jordan Terminal. "I've been impressed with the personnel, and I'm sympathetic; they're really struggling to find the least intrusive way to accommodate a moving target," Speck says. "But there is a side of me that wants everything in the right place. Hopefully, at some point the airport can make it really fit, but right now, they're just coping." (Speck recently attended a symposium on airport design in the TSA world, and "Every airport doesn't know what they should do with the machines," he says. "We'll have to try several different things.")

The good news, from Speck's perspective, is "that the overall character of the airport, so far, has held up pretty well." He mentions Robert Venturi's 1960s dictum that modern architecture "has to withstand the cigarette machine" -- "all the detritus of late-20th-century life. We knew [when designing the terminal] that things like this could happen. We didn't realize the scale, but the investment the city made in the character of the building was in ways that wouldn't be screwed up with one more x-ray machine. It's still open and grand and isn't compromised."

The Austin Way of Travel

Outside the terminal is, perhaps, a different story; the change in post-9/11 travel patterns has led to empty spaces in the parking lots and near-constant congestion at curbside on the lower level. "One of our complaints about Bergstrom from the very beginning is the lack of adequate curb space for all that happens there," says taxi driver Hannah Riddering, who chairs the City Council-appointed Airport Advisory Commission. "They can't accommodate more activities on the roadway."

This despite the fact that Riddering suspects traffic is actually down more than the 15% or so reflected by the official statistics: "I can tell you, in hard numbers, that the number of taxi loads at the airport is half what it was" before 9/11. "That directly impacts revenue, since the taxis that load at the airport pay a dollar for the privilege. And as travel gradually came back [after the three-day shutdown of U.S. airspace], companies learned they had way more business trips than were actually necessary. They could handle things online or over the phone. And there's a segment of that business that I don't think will ever come back."

The Barbara Jordan Terminal can be expanded to contain more gates, but the lower level can't grow with it. Right now, the terminal has more curb frontage upstairs than downstairs, which is the opposite of what the ABIA Master Plan Update says should be the case. (Even if you could turn the terminal upside down, the lower level curb would still be several hundred feet too short.) That's a big reason why the plan calls for a second terminal building, which was "a little surprising" to Riddering, "but it makes sense. But obviously, that's going to be very expensive." Both Smith and Speck note the alternative -- expanding the Barbara Jordan Terminal to 52 gates -- "creates operational conflict in the meantime," in Speck's words. "The appeal [of a second terminal] is that you can do construction without disrupting." Smith adds that building a second terminal -- and, decades from now, a third runway -- "is a more efficient use of our 4,200 acres."

Indeed, one of the arguments for moving the airport to Bergstrom -- which in land area is six times the size of Mueller -- was so Austin would never again have to contemplate relocating 30,000 people to expand the airport. Which makes it curious that the ABIA Master Plan Update recommends that the city acquire 85 more acres of land, on the north side of SH 71, for future parking and rental-car facilities -- especially in light of the gravity of the decline of both revenue sources.

"The assumption is it's cheaper to buy more land for surface parking than to build a garage," says Smith. "But that may change. When the building was opened, it was assumed that private parking would open at the same time and there would be 3,000 additional spaces. We still assume that, but there will eventually be more valuable uses than parking" for land near the airport. "When that planning level comes up" -- that would be when the airport hits 13.2 million passengers -- "we'll be taking some guesses about how the private sector will respond. If the airport gets into a bind and doesn't have enough cash to build essential facilities, like gates, then you'll look to the private sector to deal with parking." There are currently more than 10,000 spaces at Bergstrom.

Bergstrom's current parking-revenue doldrums were -- before Popeye's -- what last brought the City Council into public conflict with the Dept. of Aviation. The airport not only proposed, but began to implement a plan to do away with the 30 minutes of free parking now enjoyed by Bergstrom visitors, before getting the council's OK. This would, logically, have made the congestion problems on the lower level even worse, and Daryl Slusher, claiming "This would cause more trouble than it was worth to get the funds," moved to spike it. "I know this is a disappointment for you, Mr. Smith," Mayor Gus Garcia noted from the dais, "but the airport still made money, and we still want people to come and park for half an hour."

"When that came before [the Airport Advisory Commission]," says Riddering, "we voted to keep the 30 minutes," but staff "reported that the board passed the department's plan 'with reservations.' That's the kind of thing the airport does, and they do it deliberately. We're there to try to find out what's happening for the council and the traveling public and the citizens of Austin -- and they would much rather let the professionals handle it. So when we have concerns about customer service or whatever, they say we're micromanaging."

This is certainly not the first time Jim Smith, in his long career with the city, has been accused of indifference to public input or to council wishes. But most people, in most cities, do not have high expectations of their airports -- they are assumed to be unpleasant and hostile places, run with both eyes on efficiency and the bottom line, and if you have to pay to park even for five minutes and eat at Popeye's, oh well. Bergstrom is expected to be otherwise -- people care about whether it is properly welcoming and exudes an Austin flavor. As with most other functions of city government, Austinites' high standards add another layer of challenge to the job.

"Our business strategy at the airport is 'quality service, Austin-style,'" Smith says. "We intend to try to be a high-service airport -- we've chosen not to be a low-cost airport. And 'Austin-style' means not being the same. We need to distinguish ourselves and do things differently."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.