Riding the Tech Titanic

Battered by the bust, Austin awaits the next wave

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., March 15, 2002

High tech is booming

Life sucks now for everyone else

What's a Dell to do?

Two years ago, if we had been smart, we could have saved time by simply running the above haiku in place of the Chronicle news section -- along with a list of people who had left their high-profile gigs to join dot-coms. In reality, our lead story two years ago this week (written by this reporter) was about Austin's horrendous transportation problems and what we could do about them. Like we said. (Michael Dell did, in fact, turn up in that story. We also reported on the Statesman's lead tech reporter leaving to join a dot-com.)

At the time, it seemed obvious that Michael Dell and Austin's other big-rich tech titans, and the companies they ran and helmed, would be the do-ers of the decade to come. Tech Austin would have to, or want to, tackle problems like traffic and affordability and the digital divide, and even if those ills weren't cured, they could at least be brought into remission before they dealt fatal blows to the local quality of life that helped make Tech Austin possible and powerful. Nobody else in town had sufficient money, marbles, and chalk -- and, in the minds of at least some people, nobody else in town had proven to be smart and clever enough to deal with the downside of the boom.

Oh, it seems so long ago now. The bubble has burst, and Byte Boy and Click Chick are licking their wounds and trading in their Porsches, and 25,000 or so tech workers are carrying pink slips, and Kirk Watson -- the avatar of Tech Austin's approach to public life -- is gone and nearly forgotten. And much of Austin's civic elite, the people with whom Tech Austin wanted to partner in "social entrepreneurship" and community redevelopment, got left on deck singing "Nearer, My God, to Thee" as the RMS Austin-Dot-Com slid beneath the waves.

Now that the industry shows signs of a rebound, the tech titans are ready to dip a toe back into the water. But Tech Austin's relationship with the community may never be the same. On the one hand, Austin still needs its tech industry -- its intelligence, commitment, and of course its money -- to solve the problems that didn't go away with the dot-commers. On the other hand, a lot of Austinites -- including people running for office and such -- don't like or trust the techies, blame them for many of these same problems, and took undisguised pleasure and solace in the bust. What's a city to do?

Attitude Is Everything

This dualism has been a hallmark of Tech Austin's relationship with the community at large during both boom and bust. The benefits and dividends of the boom are pragmatic and concrete and easy to understand. "The upside was, and is, jobs, jobs, jobs," says Robin Rather, CEO of Mindwave Research, former chair of the Save Our Springs Alliance, and once-and-future mayoral prospect. "And whether you were a waiter or a flower delivery guy or an administrative assistant, there were a zillion more jobs and a lot of jack in a lot of pockets."

The downsides of the boom are, by contrast, largely normative and emotional. Certainly, impacts like traffic congestion and skyrocketing housing costs and economic inequity can be measured and duly fretted over. But their real import in local public life is that they piss people off, and thus they tie into all the things outsiders dislike about the techies. "By comparison, what the upper end got was comparatively disproportionate to what most people got out of the boom," Rather continues, "and that has led to a lot of resentment. And the yuppie attitude problems caused resentment too, and rightly so. In a place like Austin, that stuff just didn't fly."

It's dangerous, of course, to view Tech Austin as a monolithic mass of yuppies sipping on high-priced mixed beverages (good as that may have been for the live music industry) who were once unpleasant and are now irrelevant. "The tech sector still has political power in Austin, and in reality, they have had it for a long time," says Dave Shaw, vice-president at the TateAustin PR firm and president of the Austin Public Library Foundation. "It's not just the high tech happy hour, Porsche-driving, Docker-wearing, twentysomething dot-com set. It's the tech leaders who were here before the boom, and who will still be here long after the recovery."

But it was the Masters-of-the-Universe spirit embodied in the dot-commers, and not the good gray eminences of IBM and Motorola, that helped animate Tech Austin's engagement in civic life, in bravura gestures of philanthropy and policy and politics, in a way that promised much more to come than has come since, and promised something more than just good corporate citizenship. They were very smart, very impatient, and very rich, and if they couldn't deal with Austin's quality-of-life problems, nobody could. This attitude may have been more prevalent on the outside than in the industry itself, but it was there, too.

Tech leaders are now willing, and perhaps even proud, to acknowledge their fallibility and use the H-word. "A good thing is that some of the hubris is gone," says John Thornton, managing general partner of Austin Ventures. "The last 18 months have not been terribly accretive to the confidence of a lot of people in Tech Land. But the bad thing is that most people have a finite supply of energy in any given day, and many tech execs don't feel they have a lot to spare at the moment."

And neither, apparently, does anyone else, which is why, since the bubble burst in late 2000, not much ground has been gained against the problems on Tech Austin's short list -- education and transportation most especially. But then too, the last 18 months may have rewritten the list. "The most insidious impact of the tech boom has really been on Austin's culture," says Rather, "not just on its environment or infrastructure. We need to use this pause to reflect on how to protect the unique small businesses that provide irreplaceable vitality, how to head off gentrification, how to mitigate our affordability disaster. When people see places like Liberty Lunch going down, they see that Austin is losing its essence."

Austin's To-Not-Do List

If the bust -- which Rather, in all sincerity, describes as "a gift we need to honor" -- has taught the techies and the community anything, it's been to not kill off places like Liberty Lunch, since that was no inevitable consequence of change. Back in the early Watson era, it occurred to nobody that, if the city got into bed with Computer Sciences Corp. or Intel, it would have to apologize to the constituents later. But here we are, with the building that displaced Liberty Lunch now being shopped by CSC to other tenants, and the Intel cadaver looming over its second Austin Music Awards show, with still no decision about its future.

"We shouldn't be doing business with that kind of company," says Rather, who as SOS chair helped convince companies like CSC and Intel to put their complexes downtown instead of over the aquifer. "CSC at least showed up, but Intel alone set back the camaraderie between Austin and the technology industry at least 10 years. And they've paid no price for their contempt for Austin's leadership and vision. They don't deserve us."

The city's entire Smart Growth strategy, a vast and complicated web of policy initiatives, has been distilled into the single word "Intel," which is not good either for the industry or for Austin's attempt at growth management. Unfortunately, avoiding engagement with the tech industry so as to avoid another Intel doesn't really help anything. "Getting tough is a lot easier, but not nearly as productive," says Austin Neighborhoods Council president Jim Walker, director of the Central Texas Regional Indicators Project. "There's still a need for the upper and middle echelons of the economy to be engaged in civic affairs. The people on the other end of the scale are."

Austin could afford to be a hell of a lot savvier, though -- engaging is one thing, giving away the store is quite another. "There is, and should be, a little more parity now," says Rather. "Before, the companies had all the mystique and sex appeal and power. A good thing about the rise-and-fall is that the city has a better sense of the worth of what it brings to the table, and that those companies may have feet of clay."

On the other hand, Tech Austin is probably justified in flinching at a repeat of the late-Nineties gold rush, when every nonprofit in town -- but particularly the arts and cultural institutions -- aimed to squeeze enough sugar out of the tech titans to meet every unmet need. "One of my biggest concerns is that Austin scoped a great deal of its civic ambition when the Nasdaq was between 4,000 and 5,000," says John Thornton. "Both money and energy are now in a lot less abundance."

The Library Foundation, which in 2000 -- with Watson publicly endorsing a new downtown central library project -- appeared to be next in line to visit the tech-money trough, has instead drawn the short straw. "A new project of that scale is a challenge right now. People have less money to give and they're working hard just to fulfill existing philanthropic commitments," says APLF president Dave Shaw. "The Austin economy may be battered, but it is not beaten. Or at least that's what (local business pundit) Angelos Angelou told us in his latest economic forecast. I suppose he hasn't tried to ask for philanthropy dollars."

The flip side, if there is one, is that what tech money and energy there is can be directed toward something other than making showy, competitive gifts to art museums and concert halls. (As Rather notes, "Too much went to art, the environment got almost nothing, and poor people got very little.") Shaw cites the example of Pavilion Technologies adopting People's Community Clinic. "What Pavilion doesn't give in money -- and they still give a lot -- they give in time. They adopted PCC because basic needs like health care must be met. Companies are engaging in a way that's low-key and focused on the basics."

Diversity and Velocity

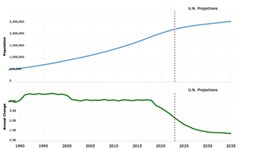

Just as Tech Austin can diversify its interests in civic life, the community could afford to diversify its vision of economic development, says Jim Walker, whose Indicators Project data highlight just how King-Cotton high tech has become in Austin. "Industries always have a hard time learning different habits; it's the public sector that needs to consider how concentrated we got in this one industry -- which was very purposeful, over the years."

In addition to the practical impacts a more diverse economic base may have on employment, income, and affordability, Walker notes that "the culture also suffered from becoming dependent on the high tech clientele. When the Austin economy was smaller, clubs could ride out the cycles, but now property values and rents are too high, and we lose clubs that aren't really catering to the tech people. Steamboat is an anomaly, rising like a phoenix from the ashes. Fourth Street is more typical, and that's totally built on a tech clientele."

We may have little choice but to diversify (perhaps into the new darling of the Chamber of Commerce set, biotechnology). As Thornton puts it, "One of the issues for business leaders is more like the late Eighties than the late Nineties: How do we continue to attract great people and interesting companies to do business in Austin?" The boom forced "all types of civic leaders to (recognize) the importance of getting out in front of sustainability issues. But ... we are going to need to actively cultivate growth, rather than just assuming that it will happen to us or for us."

In other words, the Watson-era tech boom is unlikely to be repeated in our lifetime -- though that may not be for lack of trying. "My sense is that, if the conditions were right, the industry would be even more hell-for-leather than it was," says Rather. "There's much more of a sense that the clock is ticking, and that somebody else will mop up the messes later."

Austin has been through this before. Much of the bitter conflict attending the enviro wars that preceded the tech boom, including the fight over the Save Our Springs Ordinance itself, came from developers trying to bring back the previous real-estate boom of the 1980s, despite the changes that had happened both in market conditions and, far more importantly, in public attitudes.

But compared to the heavily organized developer community of a decade ago, with its franchise on all "pro-business" political positioning, Tech Austin "is still wandering," says Rather. "There's been, maybe, 20 high-end, incredibly smart and wealthy megastars who have been and are still giving up their energy and money. But there's a lot of potential that's gone untapped because most techies, the folks in the middle, are apolitical and haven't organized themselves."

Which means, despite the bruises and hurt feelings, that this strange relationship still has a long future ahead of it. "There are too many talented, smart, tech leaders who have something to offer the community," says Shaw. "I'm sure this recent dose of humility will make everyone's future service to the community that much more thoughtful and valuable." n

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.