Staff Infection

Sick of Low Wages, UT Staff Vow Three-Day 'Burnt Orange Flu'

By Erica C. Barnett, Fri., Sept. 1, 2000

Johnnie Conley worked at UT for almost 11 years before she decided to take a second job. Conley, a reticent, bespectacled administrative assistant in UT's aerospace engineering department, had never been one to make trouble or complain too loudly when asking politely would do. But after more than a decade of service to the university -- nine years of it in the same department -- Conley noticed her paychecks getting smaller and smaller, even as her base salary continued, in spurts and trickles, to rise.

So now Conley -- a single mom who lives with her disabled adult son in a modest home -- works nights as a telephone enumerator at a state agency to make ends meet. "I held out as long as I could not taking a second job, but it got to the point where I had to," says Conley, who spoke with me before heading to her night job. "I'm trying to give my son a chance to find something for himself. He's dependent on me for everything."

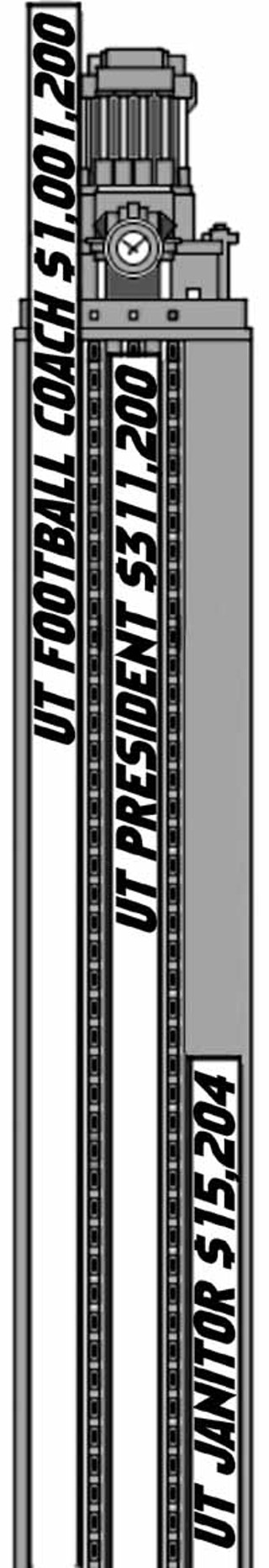

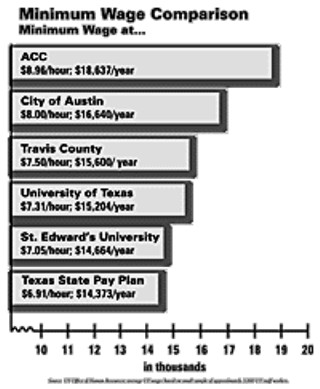

Even by her own account, Conley isn't among UT's worst off. She makes $26,000 a year, a fortune compared to the university minimum of $15,204, the starting salary earned by janitors, groundskeepers, guards, and cashiers. (As recently as 1998, the minimum salary for a full-time worker at UT was $11,076.) Even so, rising insurance and parking costs at UT have flattened whatever gains moderate-income employees like Conley might have seen from the university's most recent staffwide raise, around $50 a month for employees making less than $30,000 a year. (Individual salary increases, which will come from a total funding pool equal to 6% of the classified salary budget, may be augmented by merit raises after the $50 increases are all paid out; but how that extra money is divvied up is up to the discretion of each department.) Dental treatment, once covered by UT's insurance plan, has become "optional"; employees who wish to opt in must pay as much as $73 a month. Meanwhile, the cost of parking at UT has leaped to $25 a month, or $290 a year. (Among state workers, only UT employees must pay for their own parking costs.)

Employees with children will take an even greater hit. Verta Thompson, a senior administrative assistant who makes $39,700 a year, won't get the $50 pay raise because she makes more than the $30,000 ceiling UT set for raises. She will, however, have to ante up anywhere from $12 to $68 more each month for health insurance for her four-year-old, because of a premium increase that UT officials have called unfortunate but unavoidable. "People doing comparable jobs in the private market make $49-50,000," Thompson says. "I like what I'm doing. I like working with students. But I can take so much."

Sick and Fired?

Stories like Conley's and Thompson's are what drove Peg Kramer, a graduate student coordinator in UT's School of Social Work, to form the University Staff Association, a campus-wide group that works to improve pay and working conditions for UT staff. After organizing, pleading with UT president Larry Faulkner, and generally being a thorn in the institution's side for much of the past three years, Kramer and her organization have plotted a new, more desperate, strategy: On September 6-8, this Wednesday through Friday, the approximately 400 members of USA (along with, Kramer hopes, about 6,000 others) will stay home from their jobs in a mass "sickout," a move Kramer calls a "last-ditch effort" to get the university to listen to staff demands.

USA members hope the sickout -- officially called the "burnt orange flu" in staff association literature -- will call attention to the organization's list of 17 core demands, among them a $321 monthly increase (to a minimum "living wage" of $9.16 an hour), paid dental insurance, free parking, tuition and fee waivers, and a moratorium on increases in health insurance costs. Currently, according to John Moore of UT's Office of Human Resources, staff salaries lag the Austin market average by around 8%; USA disputes that number, saying the true disparity is closer to 15%.

But can the sickout elicit enough support from UT's 7,800 staff members to draw the attention of administrators up in the UT Tower? At UT, where employee radicalism is often tempered by a well-founded fear of retaliation, staff members are understandably ambivalent. Terry Moore, an assistant in the university's development office and a member of the Texas State Employees Union, has been a particularly vocal opponent of USA's efforts. As Moore sees it, USA's sickout threatens to erase whatever advantages university staff have gained through years of slow, painstaking negotiations. "Right now, it's clear to me that 6,000 to 7,000 people are not going to walk out," Moore says. "I think by engaging in this illegal activity, we're going to expend all of the political capital we've built up over the last three years, especially if the walkout is unsuccessful."

UT administrators say the sickout amounts to an illegal work stoppage -- a strike -- and will be treated accordingly. When the sickout was announced, President Faulkner responded by issuing a letter warning staff in no uncertain terms that if they walk out, their jobs may not be waiting for them when they return. "I will always defend the right to free speech and association on this campus," Faulkner wrote. "However, I also have an obligation to let you know about -- and to enforce -- state law regarding employment and organized work stoppages. ... Any employee who is found to have used sick leave under false pretenses will be subject to disciplinary action, up to and including termination." (Kramer argues that because the sickout is for a limited period, and because, under university rules, employees don't have to provide a letter from a doctor until they're absent for more than three days, it isn't technically against the law.)

Rick Levy, legal director for the Texas AFL-CIO, says he's surprised the university is taking such a rigid stance on the sickout, whether it's technically legal or not. "It's unprecedented for the university to take such a pre-emptive and intimidating stance toward a group of people with legitimate grievances," Levy says. "This is directed at people who are raising their voices against university policy."

For President Faulkner, the sickout -- if it happens -- will be a test of both his will and his diplomatic abilities. Earlier this month, Faulkner asked the UT regents to refrain from raising his salary above its current level of $233,000. (Faulkner also receives a housing allowance, a car allowance, and deferred compensation.)

Although Faulkner says only the most "aggravated cases" will likely lose their jobs, his letter and subsequent comments in the media have made many lower-paid employees, like Johnnie Conley, think long and hard about the risks and possible ramifications of participating in the sickout. With bills to pay, a mortgage, and a dependent son to think about, Conley isn't sure she wants to risk losing her job to take a principled, but possibly futile, stand. "I want to [participate], but I'm the sole source of income in my household," Conley says. "If I lose my income, there is nothing to keep it going while I look for something else. ... I can't afford to do without a paycheck."

Whose Money Is It, Anyway?

But beyond the risks individual employees face is another, more daunting, question: How much can anyone, including President Faulkner, do to improve wages and working conditions at an institution that is largely funded and governed by the state Legislature, not UT administration? According to Mary Knight, the director of UT's budget office, about 80% of the school's education funds go to pay for salaries; the remaining 20% pays for miscellaneous operating expenses like utilities, computers, books, and travel. Although Faulkner has a major hand in deciding what goes into UT's budget request before each legislative session, only the Legislature can determine how much, if anything, will be allocated for raises from year to year.

"I would like to invest more money in staff, but the problem is that money comes either from the Legislature or from students and parents in the form of tuition increases," Faulkner says. "There is not a body of unused money, recurring money, that's just sitting around waiting to be spent. And it has to be recurring money because it has to be available from year to year; it can't just be an occasional gift."

Opinions vary on how much additional money UT would have to come up with to increase salaries to the level USA is demanding. Faulkner says such an increase could cost upward of $100 million; Moore from the Office of Human Resources calculates that boosting salaries by the equivalent of $2 an hour across the board ($9.31 for the approximately 50 workers making the university minimum) would cost about $4,200 per worker, or around $33 million in all, a "fairly expensive" sum.

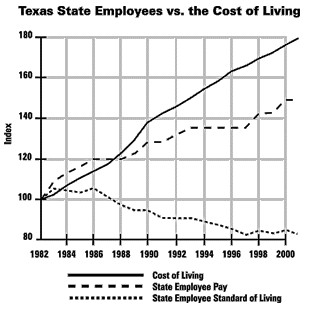

But that figure may be just about in line with what workers have lost over the past decade. The Texas State Employees Union, which represents about 1,000 UT employees, has lobbied for decades to improve wages and working conditions for state employees, over half of whom are faculty and staff at Texas universities. Currently, according to TSEU vice president Mike Gross, it would take a $4,800 salary increase to bring the average state worker to the level an equivalent state worker was making in 1988. And that's a separate issue entirely from health care, which Gross says is "going up at rates that no employers and no consumers can afford."

But TSEU isn't catching the USA's burnt orange flu. Instead, Gross says, the union will ask the Legislature for a $200 monthly pay increase for all state employees, along with funding to pay for projected increases in health care costs. "Workers are just against the wall trying to pay for health care," Gross says. "The workers don't have it. Most of the workers are barely making it, and they don't have the money to come up with the difference." What university workers lack, Gross and other union members believe, the Legislature can provide. But striking, they insist, is not the solution.

"One reason the pay lags behind [at UT] is that people don't have the ability to collectively organize and bargain for what they want," the AFL-CIO's Levy says. Instead of staying home for three days, he suggests, embattled employees would do better to join a union, where they would find the support of thousands, not hundreds, of aggrieved state workers. "When you join a union, you have the power of workers all over the state."

Whether dozens or thousands walk out next Wednesday, UT staff appear in consensus that something -- wages, health insurance costs, the grievance process -- has got to change. With turnover among staff hovering above 30% (according to USA's figures, which include turnover between departments), many say there's nowhere to go but out. "This university has to take pride in the people who are making them the big bucks," says Verta Thompson, who will be participating in the sickout. "The policies have to be changed in favor of the working-class people at this university." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.