War of Words

Hays County Planning Battle Reaches Fevered Pitch

By Rob D'Amico, Fri., July 7, 2000

As stewards of one of the fastest-growing areas in the nation, Hays County officials in the past half decade took the raging bull of new development by the horns and went to work enacting some of the state's most progressive regulations to protect their rural lifestyle. They pushed the legal limits of their authority with subdivision rules that limit development density to protect well quantity and quality and ensure good roads. They embraced more recent rules that force developers to test for water availability before drilling wells, and they even embarked on discussions to provide incentives for rainwater collection systems. So with the history of these accomplishments in mind, why are many of the current Hays County stewards drawing the ire of their constituents? In the past year, County Judge Jim Powers -- the chief elected official for county government -- has been the point man in a campaign to silence opponents, or at the very least exclude them from any meaningful role in shaping the county's future. Many see it as a classic case of inexperience, since Powers and some of his peers are political neophytes who haven't had to deal with public attacks before. And the natural reaction to attack is counterattack for self-preservation, usually without any sincere communication with the enemy.

Such is the case with Powers and local loudmouth Erin Foster, a northern county resident who has led the charge against the Lower Colorado River Authority's water pipeline to Dripping Springs, as well as the county's transportation plan.

Foster, who chairs the grassroots-oriented Hays County Water Planning Partnership (HCWPP), doesn't step lightly. She continually makes the case that Powers has a poorly hidden agenda that favors big development and ignores the potential impact on residents. Since its formation last summer, the HCWPP has filed two lawsuits against the county, claiming Open Meetings Act violations, and has been a vocal opponent to the majority of county commissioners at every turn.

The volatile situation escalated last month when Powers and county attorneys fired back with threats of criminal prosecution of Foster for her actions. Additionally, they wrote letters of complaint to employers of local citizens and reporters who have taken on the county officials. To make matters worse, the judge and his allies have ganged up on the lone commissioner -- Susie Carter -- who openly questions the other commissioners' actions. In short, things have gotten nasty down in Hays County.

But what do these out-of-county political feuds have to do with Austin? A lot.

Regardless of the he-said, she-said rhetoric, the issues being debated are matters of serious concern. At stake are thousands of acres over the Edwards Aquifer that some consider ripe for development. Understandably, there is genuine fear that this rural treasure of Hill Country land might someday mirror the strip malls and commuter traffic that characterizes much of Austin and its northern, formerly rural neighbor, Williamson County.

All eyes seem to be on Hays County lately, since it still holds the potential to go one of two ways -- as either a model for dealing with rural growth or just another spoiled beauty relegated to pitiful nostalgia of the way things used to be. After all, even the best regulations for quality growth don't amount to beans if you're opening the floodgate and promoting quantity growth.

These Are the Days

Wimberley rancher and County Commissioner Bill Burnett's roots are steeped in county politics. He is the son and the grandson of a county judge. Public office may be in his blood, but not necessarily contentious politics. "When my father was judge, there wasn't a whole lot going on," he says. Hays County even 10 years ago was -- with the exception of San Marcos -- just a rural county where squabbles didn't surpass the usual fights for road maintenance between precincts. "The last two years, we've really seen the growth ... and people are going to figure out this is a great place to live," says Burnett, now nearing the end of his first term as commissioner. "Clearly, you're going to have growing pains."

Those pains include reproaches from longtime residents who see their rural dream homes being crowded into suburbia. Burnett says he tries to take the criticism, even being called a "crook or an idiot" in stride. "Getting sued and getting called bad names is part of the business, and if you can't handle it, get out of the business." But he also bristles at what he says are untruths making the rounds, particularly the one that set off a firestorm of allegations of secret meetings and backroom deal-making in Hays County. It all began last summer at one of this area's favorite institutions -- the Salt Lick Barbecue. The HCWPP filed a lawsuit against the county alleging that a quorum of commissioners -- Powers, Burnett, and Russ Molenaar -- attended a meeting at the restaurant and discussed policy and business, a violation of the Open Meetings Act. The event was sponsored by Newhall Land and Farm Company of California, which had a proposal to build 14,000 homes on the Rutherford Ranch over portions of the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone.

Burnett has been accused of taking an active role at the Salt Lick meeting by making a presentation on growth and the county's future. "That's a total lie," he says, noting that he spent the evening hanging out with the sheriff and drinking beer. A district judge dismissed the lawsuit, but the HCWPP is appealing the ruling. Regardless of whether the three officials did any county business, the appearance of impropriety was enough to kick-start the formation of the HCWPP, which saw a connection between the Newhall plan and the proposed LCRA water pipeline to Dripping Springs. The group began actively fighting the pipeline and other plans they say are paving the way for large-scale development.

The lawsuit also had the effect of polarizing county residents, since Powers seemed to take the attack personally and subsequently deemed anyone connected with the HCWPP persona non grata in his court or in any other public discussions. HCWPP members were excluded from an oversight committee designed to plan for the LCRA pipeline and a committee to plan for future transportation. Foster says she was told by more than one county official, "No planning partnership member will ever serve on any county committee." She says the county's attorney, Jacqueline Cullom Murphy, eventually even told her, "You are not to talk to anyone at the county."

Road Plan Switcheroo

The HCWPP succeeded in stopping a transportation plan for roads into the year 2025 that included what amounted to an extension of MoPac to San Marcos and several new four-lane roads over the aquifer zones. Their action awoke the slumbering residents of Wimberley, who also objected to several of the proposed roads and protested in droves at a public meeting to discuss the plan. Faced with an onslaught on all sides, the Commissioners Court formed a blue ribbon Committee to make recommendations for the plan, which eventually would be submitted to the Capital Metropolitan Planning Organization (CAMPO) as official input on what roads should be funded in the future. The 19-member committee came back with recommendations for no major roads over the aquifer zones, no MoPac extension, and several other changes. The Commissioners Court seemed to adopt the recommendations in toto, with a minor change in a road designation. But the plan that showed up on CAMPO's doorstep last month failed to include the committee's "overlay" showing where the roads over the aquifer zones should remain minor neighborhood streets, and the alignment of a proposed road into Rutherford Ranch shifted west, deeper into the aquifer's recharge zone.

While dumbfounded committee members wondered how the changes were made, the HCWPP came out with a blatant accusation. They claim that Burnett made the changes illegally with county staff before giving the plan to CAMPO, where he serves as a Political Advisory Committee member. The HCWPP troops once again filed a lawsuit claiming a violation of the Open Meetings Act, and Foster pushed for criminal charges to be filed against Burnett and others. (Burnett denies the allegations, but won't comment on them specifically due to the lawsuit.) The court met to correct the lack of the overlay and another change, but left the westward shift in the alignment without much explanation of how it ended up that way. And once again, Foster's attacks led to even more personal indignation from Judge Powers.

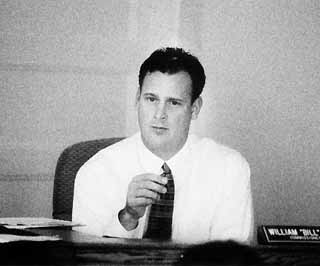

Here Comes the Judge

Like Burnett, Jim Powers is also in his first term after replacing two-term judge Eddie Ethridge in 1998. The 42-year-old Dripping Springs area resident owns a couple of Popeye's fried chicken franchises and is active in the local Baptist church. In addition to the Salt Lick brouhaha and his refusal to address the confusion over the road plan, say HCWPP members and others, the judge has made several questionable actions, including:

Powers did not return more than five phone calls requesting an interview about his background or to comment on the accusations. However, an examination of past comments and correspondence seems to confirm that he does not take criticism lightly, and sincerely believes that questioning his authority and integrity is not only out of line, but punishable. The judge's agenda is driven by a belief that growth is inevitable and therefore should be ushered in to somehow benefit existing residents. In other words, developments hold merit if they simply meet the county's subdivision guidelines and provide quality infrastructure. After approving the Coyote Crew development district, Powers was quoted by the Austin American-Statesman as saying "This is a way to get roads built, infrastructure built without costing you, the taxpayers, anything," even though developments such as the resort, which includes plans for 300 homes, create a demand for more infrastructure. He maintained a similar stance in written comments about the Newhall proposal. "Newhall also committed to share the expenses of upgrading the roads necessary to carry the traffic for the new development. We're talking 'millions of dollars' that taxpayers would not have to pay. With Newhall out of the picture, there is no way to predict who will be next."

Powers and the rest of the court majority -- Burnett, Molenaar, and Debbie Ingalsbe -- don't ever seriously consider whether they could actually stop a development if necessary, or even make such an attempt when it's in the best interest of the county. They merely note that all development is inevitable. To their credit, they are champions of subdivision rules and other efforts to control growth. Burnett also talks of getting more regulatory power from the Legislature (since counties don't have zoning authority), rainwater collection incentives, and efforts to preserve open space. But he stresses the need to plan for new roads and other infrastructure to avoid "ending up like Austin," with severe congestion from lack of planning. He was also the impetus behind an attempt to extend Escarpment Boulevard to Hays County into prime development areas in the CAMPO 2025 plan.

In light of these actions, more of the locals are starting to question that fine line between planning and promoting.

The Rabble-Rouser

If you had to name the top troublemaker in Hays County, it would have to be Erin Foster. She's not exactly the Lone Ranger in her battles for justice -- a host of activists have sprung to action since the Salt Lick event, while others have been plodding along for years. Jim Camp, for instance, has long fought for water quality in the area and this year won a seat on the Barton Springs/ Edwards Aquifer Conservation District Board, serving alongside such other environmental advocates as Craig Smith and Jack Goodman. To some degree, the HCWPP is but a drop in the bucket of activism, since strong community boosters and political junkies have been entrenched in Buda and Wimberley for years. (Not to mention San Marcos, which is another story.)

But all told, Foster is probably the loudest and most obnoxious of the Hays County activists, partly because she's not easily intimidated, and partly because she revels in the role. She often punctuates her complaints with phrases like, "I just wish they'd try it." To some degree, she likes trouble. But whatever her style, her motivation, she says, is to preserve quality of life for existing residents.

A real estate broker and former mayor of the Village of Bear Creek (a subdivision she helped get out of the Austin ETJ to incorporate), Foster also sued the Austin Community College District for its attempt to put a campus over the aquifer. And she joined the Save Our Springs Alliance board for a stint after the group joined her in the ACC lawsuit. She first became involved with water issues after noticing that Bear Creek would never be able to afford a surface water supply, but that newer developments in the Dripping Springs area were successfully clamoring for surface water infrastructure from LCRA.

Since the LCRA pipeline and road-plan battles began, she hasn't missed many opportunities to speak out against what she sees as back-room politics. But now, county officials are starting to fight back. Last month, Commissioners Court referred to some of her recent actions as possible criminal conduct and offered the "evidence" to the county's district attorney.

Jennifer Riggs, the county's hired legal counsel, sent Foster's attorney a letter outlining what she calls "extreme" and "defamatory" behavior, and an improper offer to end a HCWPP lawsuit against the county. Riggs says she sent the information to Michael Wenk, the Hays County district attorney. But although she cited several sections of the penal code in reference to Foster's recent actions, Riggs says she did not make any legal determination of whether the actions were indeed criminal.

The improper offer that Foster is accused of making occurred at a May 30 Commissioners Court meeting, when Foster handed Powers a note as the judge headed into executive session to discuss the HCWPP lawsuit. The note read: "Judge Powers & Commissioners. The HCWPP lawsuit filed last Thursday [over changes in the transportation plan] can be dropped if the original May 1, 2000, map is approved with the changes already adopted in court." Foster agrees that she gave Powers the note and made other comments the county officials found objectionable, including her own threats to seek criminal prosecution of Burnett and others.

"Commissioner Burnett violated the law," she said in public comments before the court on May 30. "He changed a government document, passed it off to CAMPO, and he got caught, and it is time for you people to realize that we're not going to put up with this, so I urge you to carefully consider your votes today, because by voting for the new changed plan, you reveal yourself for being part of the conspiracy ... It must be worth quite a bit to be willing to go to jail for it.

"I urge the County DA and the County Sheriff to press criminal charges."

Making an offer to drop a lawsuit in the same time frame as threatening criminal action is "extremely troubling," Riggs wrote in the letter to Foster's attorney. "The blatant purpose of Ms. Foster's offer and threat is political -- to attempt to influence the votes of the members of the commissioners court though litigation and threats, rather than through proper public comment and the electoral process." The attorney followed up the charges with sections of the penal code outlining offenses for coercion and bribery of public officials.

The HCWPP attorney, Phil Durst, brushed off the county's attack with an official response of "Yeah, uh-huh, right." He fired back his own letter to the district attorney saying Riggs' charges were "bullying and anti-democratic." Foster says it's yet another attempt by officials to silence any dissent from anyone who questions the court's pro-development agenda. She also questions how her offer could seriously be considered coercion, especially since a large number of Hays County residents believe that the road plan voted on by commissioners is indeed different than the one submitted to CAMPO. Riggs' letter states that the Hays Co. Commissioners Court "felt it necessary to refer [Foster's actions] to appropriate legal authority." But Riggs says the decision to send the material to DA Wenk was made by her and the commissioners' other legal representative, Jacqueline Cullom Murphy, who works for the county. (Wenk's only response in the matter so far was a letter saying there was no evidence of criminal wrongdoing by commissioners in the controversy over the transportation plan changes.)

Powers says he does not recall any official action by the Commissioners Court to document the charges regarding Foster, but he agrees with the decision. "Erin has a right to voice her disapproval, but she should just pick up the phone," he said in an earlier interview, although he did not return the Chronicle's phone calls for follow-up questions. Powers says his stand against Foster's improper offer to drop the lawsuit is evidence that he doesn't take sides in the ongoing debate over how to plan for impending growth, particularly in the environmentally sensitive areas of northern Hays County. The judge adds that he would have taken the same action had a developer made a similar inappropriate offer before commissioners. "I wanted the public to know that I'm not cutting deals with anyone," he says.

Meanwhile, Riggs says the county is also seeking a summary dismissal of the HCWPP lawsuit on the grounds that it is a frivolous political attack. In a letter to Durst, Riggs wrote that if the complaint was not dropped, the county would seek sanctions, meaning court costs in the event of a dismissal. Cullom Murphy says Foster "shocked" commissioners with the note and such actions as yelling, "Say no to the big money," as they went into executive session. "Those of us who are in public service see her actions as inappropriate."

She adds that the letter and referral to the DA are not an attempt to retaliate against Foster. "If that were the case, I'd go over and see if she'd paid her property taxes, which of course I won't do." Both Cullom Murphy and Riggs say that the county denies that Burnett did anything improper, but that even if he did, the HCWPP has no basis for proving any violation of the Open Meetings Act. Meanwhile, Foster says she's hired her own criminal defense attorney to ward off any future attacks.

The Lone Dissenter

Also new on the block in Hays County politics is Susie Carter, the Pct. 2 commissioner who has been cold shouldered for her willingness to listen to HCWPP members and question court actions. For instance, Carter was the only commissioner who asked for a discussion -- unsuccessfully -- on how the road plans changed, but she was ignored. Carter says she won't comment on much of the debate over her relations with citizens and commissioners, since most of it is the subject of lawsuits against the county. She says, however, that she is going to remain "positive" and work "hard and diligently" to gain the respect of her peers on the court and serve her constituents. For instance, she was the lone vote against the Coyote Crew resort development district, saying the court should take more time to study the impacts of the development. But information from other sources shows how Carter has been the target of attacks from Powers and others.

She recently was served with a slander suit from the developer of the county's newly approved $8.4 million Juvenile Detention Center after she questioned the economic feasibility of the project. Once again, Carter was the only one in opposition to the plan. Elected officials are usually insured against legal assaults on comments and actions they make in court and receive legal defense. However, the county's insurance company resisted covering Carter, and the impetus for the resistance came from Powers, according to several sources close to the court. Carter eventually got the coverage, but she continues to be harassed by her peers and other officials.

And action against her isn't always covert. In June, Carter submitted a resolution to support the city of Austin's purchase of 1,600 acres of Sky Ranch property in Hays County for an open space preserve. Her agenda item was booted, and replaced with one written by Powers.

Dealing With the Greens

Noticeably absent from the ongoing discussion is Commissioner Russ Molenaar, who shares no love for Foster or the HCWPP. Molenaar was on vacation and could not be reached for comment. But the commissioner, who has served the Pct. 4 Dripping Springs area since 1995, has been a vocal critic of the city of Austin and its attempts to control land use in Hays County. However, he also pushes for more cooperation between the two entities and complains that the city hasn't done its job of keeping county officials in their loop. In many respects, the city of Austin has a lot to share with its rural neighbor (other than new suburbanites).

For instance, if any community has a lesson for study on the effects of a polarized community, it's Austin and its developer/environmentalist wars. The Austin community has had a good run lately at open dialogue and compromise, partly because the economy is flying high and everyone recognizes that the environment is a key reason why, but also because leaders in both government and business have abandoned the politics of exclusion. Nowadays, inviting your enemy to the table is seen as a strategic advantage. With a Commissioners Court full of relative newcomers to elected office (no one has served longer than five years), many believe that some of the thin skin worn by the officials needs to be shed in favor of something a bit thicker. Even some of Powers' allies concede that it isn't adept leadership to attempt to discredit opponents or get them fired from their jobs, even if that's their intent toward him.

Powers and others, such as LCRA officials, put much of the blame for their stances on the HCWPP lawsuits, which they say create a climate where they have to exclude opponents who are taking legal action against them. As for Commissioner Burnett, he says he wants to focus on the future and has been talking recently with Austin Mayor Kirk Watson about holding more meetings between county officials to learn and cooperate. The Austin mayor, according to Burnett, wasted no time taking a jab at Hays County's recent foibles. "Watson joked," says Burnett, "about meeting at the Salt Lick." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.