A Whole New Ball Game

Colorado River Park: Different Strokes for Different Folks

By Dan Oko, Fri., Dec. 17, 1999

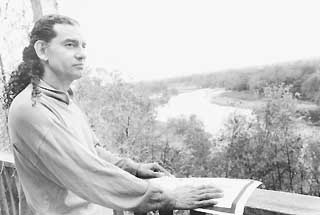

The view across the Colorado River from David Moriaty's porch makes it easy to understand why he has spent the past 20 years lobbying the city of Austin to preserve the land. A band of trees hides the softball fields and parking lots from view, so that the only visual cues about what lies beyond are a handful of lights standing high above the tree line. A small herd of deer suddenly bursts from cover. A red-tail hawk floats above on a steady breeze. Below, cormorants, egrets, and a great blue heron wade in the water, escaping the Longhorn Dam as the river gains a current approximating how it must have run before the creation of Town Lake. Given that last year voters approved bonds that will provide $10 million toward the development of the Colorado River Park on 363 acres in Southeast Austin, you'd expect Moriaty and his nature-loving neighbors to be pleased. After all, parks advocates see this project as a way to expand recreation programs and a unique opportunity to set aside a little more green space in the face of booming development. In turn, the Austin Parks Foundation, a local nonprofit group that has been raising money for park development, has hired Hargreaves Associates, a San Francisco-based landscape architecture firm that specializes in riverfront land, to design a park suited to the landscape and community.

But despite the vision that is finally being drawn up for this last bit of urban wilderness, Moriaty and others remain skeptical that the outcome will represent what's best for this tract of green. "I see this plan as very shortsighted," Moriaty says. "This is shortsighted because the impulse is toward urbanizing it. What we have here is such an incredible resource that remains only by accident, because for so long East Austin was beyond the pale, and we should be very careful about developing it."

Considering the voices clamoring for a piece of this verdant pie, it's easy to see the rationale behind such preservationist impulses. At a mid-November meeting at the Montopolis Recreation Center, the second of three planning sessions designed to address community concerns and build a long-term vision for the Colorado River Park, tensions ran high as various Austin constituencies laid claim to this newly hallowed ground. Soccer players called for more ballfields; bird watchers envisioned walking trails and blinds; bicyclists lobbied for additional riding paths; urban gardeners requested an area for growing natural foods -- and these are just a few of the divergent plans for the land.

Among the more vociferous voices, in addition to those concerned with quietude and wildlife, were a pair of well-organized groups hoping to prioritize their own particular visions for the Colorado River Park as an elaborate playground. On the one hand, the Montopolis Little League, which already has the city's assurance that it will get a baseball complex on site, worked to make sure that their boys and girls of summer would have somewhere to play. On the other, the Austin Paddling Club, which represents canoeists and kayakers, put forth a tantalizing vision of a whitewater play course below the Longhorn Dam.

Mary Margaret Jones, a partner at Hargreaves Associates, seems as well prepared as any public official to work with the crowd as she sought the middle ground. "Our job is to take the nature of the site as well as the historic nature of the site, and combine them into what people want," she told the assembly, noting that the geological and alluvial features of the land will guide development. Nonetheless, before meeting's end, at least one angry fellow expressed a concern that seemed to be on a lot of people's minds: "It hardly makes sense to preserve this park if we're just going to flatten it out and turn it all into ballfields."

The Plan in the Middle

Austin Parks Foundation executive director Tim Fulton has a quiet manner that belies his precarious position as the man overseeing the development of Southeast Austin's answer to Zilker Park. He's well aware that it's no accident that this park has been kept free from permanent development at this late date. Although mostly barren today, part of the acreage now dedicated as the Colorado River Park was home to a dairy farm through the middle part of this century. Hedgerows and a grove of pecan trees indicate that some of the land was probably dedicated to additional agricultural uses. Elsewhere, concrete marks the only remains of a trailer park that must have offered one of the most scenic views in Texas, if not the whole country.

"This is democracy in action," Fulton says. "What we're looking at now, it's a much brighter future than it might have been. We need to embrace open communication. It's not that we have a problem here. We have an opportunity, and it's great that at the meetings people do get a little impassioned." Fulton notes that APF isn't working from scratch when it comes to planning the park, either. In 1986, under Mayor Frank Cooksey, the Austin City Council came up with a Comprehensive Plan for Town Lake Park, which to this day provides the seeds for the Colorado River Park. Running 100-plus pages, the report was an initial attempt to "enhance and develop scenic waterways in the heart of the city." It provides a blueprint for a series of parks spanning 815 acres from MoPac to Montopolis Bridge, and it aimed to incorporate many of the uses being debated today, right down to the polemic that divides nature preserves and ballfields.

As for its vision for the Colorado River Park, the 1986 Comprehensive Plan argued in favor of a major metropolitan park that would hold a performance pavilion, an angler's lodge, a health and fitness center, and a driving range. "Just as Zilker Park has been available to grow with Austin and meet its expanding cultural and recreational needs over the last 50 years, so the Colorado River Park will be available to meet such needs for the next 50 years of the city's future," the plan reads.

But although Zilker weighs heavy in the minds of some parks advocates (see sidebar), due largely to maintenance costs and Austin's booming population, Fulton hopes the new riverfront park can be seen as an even more successful venture in urban planning. "The challenge for us as well as for Hargreaves is to come up with a vision for the park that will serve the community," he says. "With a real plan in place, you can solve the problems before they develop. What we have here is the opportunity to create a world-class park."

Jones, the Hargreaves partner, says she's looking forward to the challenge of designing a park in light of the goals of both the neighborhood and the community at large. The work Jones and Hargreaves have done in the past leaves little doubt that they may very well indeed be up to the task; among other projects, Jones took the lead in designing Sydney's Olympic Plaza for the 2000 Games. Hargreaves has also designed waterfront parks in Louisville, Kentucky, and San Francisco and San Jose, California, with an emphasis on maintaining natural amenities within an urban setting.

Just back from a trip to Seoul, South Korea, where she was working on converting an industrial dump into parkland, Jones said recently: "We're really all about finding a solution that allows a layering of uses at the site, that are appropriate to the site, so that what emerges is a coherent and dynamic whole. No one will get every one thing they want, but by going through a public process, there is an understanding that we can establish ownership and embrace the park over the long term."

The park renderings at the November meeting, which were based on surveys collected earlier in the fall, displayed an attempt to synthesize many of Austin's desires for the new park. Generally speaking, the designs left the riverfront intact, setting aside cover important to birds and other wildlife. Integrating the floodplain, the landscape architects proposed an area reserved for "passive recreation," such as picnicking and casual sports away from the river, and at the park's outer edge, closest to existing development, one plan shows ballfields and more active recreation surfaces. Where the old trailer park stood, the plan proposes building a playground or senior center.

All in all, completion of the Colorado River Park is expected to cost about $40 million. "You can't just throw up a fence and call it nature," says Jones, whose firm is being paid $150,000 for drawing up and marshaling a suitable plan. "It's better to have public occupation and appropriate human activities."

Nature vs. Nurture

So far, two youth fields and one so-called "big league" field for older players have been built as part of the Montopolis Little League Complex. Since the 1950s, the Kreig Fields softball diamonds have also been a part of the matrix of public lands surrounding Town Lake. But Montopolis League president Olga Ruedas says that the city still must make good on a 25-year-old promise that calls for four more baseball fields as well as attendant facilities, including lights and a concessions stand. "This has been in the works for a very long time," says Ruedas, adding that she doesn't have a problem with leaving the river in a natural state, "as long as the fields take priority."

This hard-line position reflects one of the biggest challenges faced by park planners and the Austin Parks and Recreation Department, which must juggle the need for playing fields with the diminished availability of natural areas within the urban boundary. The Montopolis League alone provides an outlet for more than 280 kids, ranging in ages five to 18, who participate in organized sports. Lined up next to the baseball contingent, the Austin Soccer Coalition has its hand out, while the Austin Paddling Club hopes to establish a whitewater course along the shores of the Colorado River. Given that the planning process is still in its budding stages, most agree that it's too early to discount the paddlers' dreams, but one gets the impression that despite their proven record as stewards of Austin's waterways, this group is paddling upstream.

Daniel Llanes, who lives next door to David Moriaty in East Austin, worries about the potential effect that such a development could have on the habitat that forms his back yard. "This is the last undisturbed natural setting in the valley," he says. "As more and more houses have been built, the wildlife has been forced toward the river, and now there's almost nothing left. And if we're going to manicure this, it won't be effective habitat; it's like if a tree falls, it becomes habitat. So when you manicure that, it's incompatible with the wildlife."

Neighborhood activists aren't the only ones giving voice to these concerns. At the November meeting, a representative of the Sierra Club and others opined that wildlife ought to be given at least equal consideration as baseball -- a perspective that has not escaped the park's designers, the Austin Parks Foundation, or the city's Parks Advisory Board. "What we're hearing is that there's a large group of people who care about the park's natural qualities," says Fulton. "We want to protect the wildlife but we also want to let people experience it. We feel that if a park is well planned, and you return some of the natural attributes, the wildlife can continue to persist. There's no reason humans and wildlife can't coexist."

"Compromise" is the operative word in the park-planning process, says Parks Advisory Board member Mary Ruth Holder. She views preserving the Colorado River Park as part of a broad opportunity to set aside some of Austin's natural heritage and allow future generations to view a piece of the past. "There is always [contention]," she says. "There are always people that want different things, but I think we've got a special opportunity here. I really see this as a place in our community where east meets west. It's a transitional area, where the Edwards Plateau meets the Blackland Prairie and the dammed water moves into the flowing river -- and we have an opportunity to allow the community to really see the relationship between these landscapes."

As per the draft designs, Holder says that the idea of protecting the waterfront and allowing for organized activities away from the river appears to be a reasonable compromise. "This park needs to be about the river," she says. "And then in the upland areas, we could have some sport areas. That's appropriate. I also think that having a community area, where people can visit and picnic and things like that, would be an excellent addition." She also says she would like to see youth education programs and field courses integrated into the park's curriculum at some point in the future.

For now, a third and final public hearing will take place Jan. 18 (6:30pm in the Colorado Room of Palmer Auditorium) to hammer out how the selected plan might be phased in over the next two decades. From there, the plan and public input goes to the Parks Advisory Board for recommendations. So it might be early summer before it ends up at City Council's feet. In the meantime, Stuart Strong, planning and design chief with Austin Parks and Rec, remains tight-lipped. "We're relying on the planners and engineers to let us know what's possible," he says. "So for now we're just waiting to see what the plan holds." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.