Light Headed?

What Commuters Want

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., July 23, 1999

Capital Metro has "made contact" -- often simply by handing out one of these survey cards -- with more than 450,000 of your friends and neighbors since AIM began in April, although only about 8,000 people have actually offered their input, through various channels, to the AIM database. A much smaller number, 562 to be exact -- but statistically representative and all that, were surveyed as part of the first-phase market study that undergirds AIM, and of that number the vast majority think public transit is one of Metro Austin's top three civic priorities, and that traffic is the No. 1 problem caused by Austin's growth. (For highlights of the market study, see the box on p.24.)

Up until now, in the first phase, we've heard precious little about what we might actually do to fix that problem, but now Capital Metro is focusing the AIM discussion on seven broadly defined, and often quite complicated, solutions. Again working under the assumption that we will need to implement more than one (if anything is being shoved down our throats by Capital Metro, it's this multi-modal solution stuff), Cap Met and its partners -- the Capital Area Metropolitan Planning Organization (CAMPO, the former Austin Transportation Study), the Texas Department of Transportation, and the various cities and counties -- would like the AIM process to bring at least two, but not more than four, of these ideas to the surface for further examination.

And what are the Seven Solutions, you ask? They are, in no particular order:

• Building new and better roads. This goes beyond new highway projects like SH 130 and street projects like those funded by the Austin bond binge. It also means fixing the current roads, synchronizing the traffic signals, improving the lane markings, and other ways of helping Joe and Jane Driver.

Capital Metro already pays for much of this work, through the Build Greater Austin program, and could always pony up more. CAMPO, which is responsible for authorizing all major roadway projects in Austin, is currently revising its own Austin Metropolitan Area Transportation Plan, on a timeline that approximates, but is not really synchronized with, the AIM process; the AMATP is set for adoption in November.

• HOV lanes. High-occupancy vehicle lanes should be familiar to anyone who's driven in Dallas, Houston, or on the West Coast -- the "diamond lane" is reserved for carpools, vanpools, and buses. The planners consider these public transportation facilities, and Cap Met, like its sister transit authorities in Houston and Dallas, could end up paying for them. But CAMPO, with TxDOT's blessing, is already studying "HOV concepts" for the IH-35 and MoPac/US 183 corridors.

These studies assume that the HOVs will be new, separate lanes, but have not established many specifics beyond that, such as whether the lanes would be blocked off by barriers (as in Houston), or whether they'd operate all day or only at peak hours. There are also "HOT" lanes -- which require paying a toll to use -- but so far this concept has only been discussed for the

SH 130 project, which is already a toll road.

• Busways. These are like HOV lanes, except only buses can use them. In most major cities, you'll find at least some busway lanes, usually on surface streets in congested downtowns. Busways aren't limited to existing street infrastructure -- the only semi-specific concept for an Austin busway would run along the railroad right-of-way owned by Capital Metro, much of which is well away from any current road. (This would presumably be an alternative to the light-rail Red Line using this same corridor.)

Another commonly used option is running buses in the opposite direction on what are otherwise one-way streets. Busways keep buses from being stuck in the same traffic as cars, but HOV lanes would do the same while also reducing the traffic itself. So, if HOVs are a near-certainty for Austin, it's unlikely Cap Met would invest in busways as well.

• Pedestrian and bicycle improvements. You know what these are, although this is probably the vaguest of the AIM solutions. Well, not really vague -- it's just that things like sidewalks, crosswalks, and trails have traditionally been valued in Austin (and the rest of America) as urban-design amenities, not as transportation facilities. So trying to figure out how many cars you can get off the roads by building sidewalks is not a question that's very amenable to the traditional modes of transportation planning.

The number is probably not very high, truth be told, if ped/bike improvement are an end in themselves. But the point is well made that if Austin is ever to see substantial shifts toward mass transit, the ped/bike infrastructure will have to be improved to get those riders to and from the rail station or bus stop. Given Austin's self-image and the current realities of political power in this town, it's a fair bet that AIM will be looking more closely at foot-powered transportation.

• Improving Cap Met's bus service. What a concept! This is, unsurprisingly, a favorite solution (according to the market study) of Capital Metro's current customers, and we have been hearing for eternity that Cap Met needs to be a better bus company before Austin will let it become a glamorous multi-modal transit authority. It is no accident that Cap Met's new Five-Year Plan for overhauling its "rubber-tired services" (a genuine term of art for transit planners) is being produced right at this juncture.

"Improving," of course, doesn't just mean "running on time" or "getting rid of the bad smells on the buses." The Five-Year Plan could include eliminating many marginal routes, re-aligning many others, instituting a grid system that wouldn't require a downtown transfer for every substantial trip, running all day and all night, creating more crosstown and suburb-to-suburb service, and (most of all, probably) running more often, especially at peak hours.

• Commuter rail. Just a reminder: Light rail is basically a big bus on tracks, often electric and making frequent stops, whereas commuter rail is a bona fide passenger train offering station-to-station service. With the creation in 1997 by the Legislature of an Austin-San Antonio commuter rail district separate from either Capital Metro or VIA, its Alamo City counterpart -- a pet project of state Sen. Gonzalo Barrientos, who also chairs the CAMPO board of elected officials -- the rail waters were made quite unclear. Right now, the district doesn't exist, and unless Austin, Travis County, San Antonio, and Bexar County all opt in, it will never exist, which might toss commuter rail back into Cap Met and VIA's laps.

Both of the AIM commuter rail proposals are along routes we know from light-rail plans -- the Red Line, running from Leander to downtown, and the Blue Line, from Round Rock along the MoPac tracks (and then on to San Antone), which is currently being feasibility-studied by TxDOT. Commuter rail on either line would probably knock it out as a light-rail route. Everyone says they love the Blue Line, but a big problem is that the track is already being used, and not that efficiently, by Union Pacific and other freight traffic.

• And, of course, light rail. The big news here is that the schematic advanced by the Old Cap Met back in 1997 -- first Red, then Green, then Orange, then Blue -- has been abandoned; any of these could be Austin's first, or last, or only, light rail line, if we indeed have light rail at all. If the Red or Blue Lines turn into commuter rail or busways, then we only have two choices. But we also have several sub-choices; Capital Metro has, in its words, "dealt with the reality that [it] may not have the financial capacity or potential ridership support," not to mention citizen support, to build the entire length of each line.

So the AIM menu includes two Red Lines, three Green Lines, and two Orange Lines. In all their variants, the Red and Green Lines would run at least from downtown to Howard Lane, though by different routes through the city center. The Red Line could either stop there or run all the way to Leander. The Green Line choices are at the other end; it could stop downtown, or run south to Ben White, or further south to Slaughter. The two Orange Lines, by contrast, both run from downtown to Bergstrom, but on somewhat different routes -- crossing the river either at Congress, or at Longhorn Dam, and then continuing along Riverside.

The Rail Opponents

And now what? The challenge facing Cap Met, as expressed by Karen Rae, is "to build any sort of consensus, that we can advance to the citizens, between radically different visions of Austin." At the authority's recent "community-wide transportation workshop" on July 17, the crowds in attendance -- most of whom you'd call "activists," as opposed to "average citizens" -- gave their tentative thumbs-up to ped/bike improvements, to improving the current bus service, and to light rail. However, when asked to choose a specific rail alignment, those same folks gave their strongest support to commuter rail, rather than light rail, along the Blue Line.

|

photograph by John Anderson |

Even though AIM presumes, and hopes, that we will focus on all of these alternatives equally, light rail is still the polarizing political issue -- a large chunk of the workshop crowd was vehement in its opposition to any rail, and that constituency seems to be growing. Along with the conservatives who think it a waste of money, and the populists who view it as elitist and gentrifying, we now have traditional central-city neighborhood leaders coming out firmly against rail and the higher development densities -- you know, Smart Growth -- planners envision for its rail corridors.

So it'll be interesting to see if, as the AIM process continues on, the Silent Majority of Metro Austin comes out of its political torpor and takes a definite stand on rail. (These are the folks who, according to the market study, support rail but think it would fail at the polls.) It may help when we start getting more concrete "technical work" -- that is, cost and ridership estimates -- for the various proposals, to permit apples-to-apples comparisons. Right now, we only have working numbers, based on comparisons with other cities -- they call this "sketch planning" -- for the rail options.

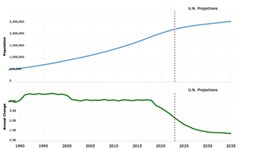

Under this analysis, we're looking at a minimum of $19 million a mile for light rail, and $14 million for commuter rail along the Red Line -- that is, on tracks that already exist and are already owned by Capital Metro. The Green Line is priced at $27 million a mile, the Blue Line (for light rail only) at $31 million, and the Orange Line at a whopping $50-$55 million. This would make the Orange Line -- the line that, we keep hearing from the public, "makes the most sense" -- cost at least $439 million, and the full Green and Blue Lines would cost more than $750 million each. (For the ridership estimates, see chart, p.22.)

Of course, TxDOT routinely drops this much on highway projects without any citizen input or referendum, but now that we, the people, have been given the vote on light rail, it's clear that rail fans will need to work hard to overcome the sticker shock. And they won't do it by talking about how light rail is "fun" or "sexy" or "appropriate to our image as a world-class city." But considering how many people seem utterly convinced that Austin can never be a great city without rail transit, expect that, even if a big light-rail system fails to move forward, a tiny project -- like a cross-downtown trolley line on Fourth Street -- will still live on.

The bigger question is whether rail will continue to figure prominently in the overall Austin transportation plan produced by CAMPO. Right now, the AMATP presumes 54 miles of rail transit, and to CAMPO planners it is absolutely necessary that we have rail and HOV and better bus service if we are to ever accommodate our rapid growth. Yet the elected officials who form the CAMPO board, chaired by Barrientos, have been understandably loath to really defend this position.

Nor have most of them been willing to ask hard questions about our rapid growth, which will in the end spell success or failure for any of the Seven Solutions. As their citizens gnash their teeth about traffic and demand that their favorite solution be built as quickly as possible, our appointed leaders continue to make land-use decisions that only make our transportation woes worse and worse, without apparent thought. As AIM aims to produce an elegant, multi-modal solution, we may end up with the answer to only half our big question.

To participate, call the AIM hotline at 637-4AIM, or visit www.aim99.org.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.