Peggy Chiao Enters A City of Sadness

UT alum returns for rare screening of Hou Hsiao-hsien's greatest

By Julian DeBerry, 8:00AM, Thu. Sep. 27, 2018

This week, Austin Film Society and the Austin Asian-American Film Festival wrap up their retrospective examination of the work of landmark Taiwanese director Hou Hsiao-hsien. On Saturday, UT alumna and noted producer and film theorist Peggy Chiao returns to Austin with a conversation on what is arguably the director’s best, A City of Sadness.

Producing and writing great, revelatory works such as Center Stage (1991), her piece entitled ‘In Search of Taiwan’s Identity’ remains one of the essential texts on the career of Hou, informing the viewer on the historical and formal roots of his seminal 1989 picture. With the exception of her parents, who “fell asleep” during the highest grossing film of its year, the enticing allure of a renowned film long gone unseen to American audiences remains.

In advance of the screening, Chiao talked to the Chronicle about Hou, his impact on the New Taiwan Cinema, his peers like Edward Yang, and her own films.

AFS and AAAFF present A City of Sadness, Sat. Aug. 29, 7pm. Tickets and info at austinfilm.org. Read more about the film itself in this week's issue.

Austin Chronicle: A City of Sadness was the highest grossing domestic film of its year and took home the prestigious Golden Lion at Venice, the first of the three Taiwanese pictures to ever receive the award. How much of an impact did the film have on Taiwanese cinema at the time?

Peggy Chiao: It gave a big boost to the New Taiwan cinema movement. During the late 1980s, people in Taiwan sneered at the new aesthetics as self-indulgent, alienated, and naval watching. The confirmation from international film festivals did not convince them that the movement was well received by international critics and scholars. Until, of course, the big three (Venice, Berlin, Cannes) gave us the golden lion. It was a headline news on every media - never has a Taiwanese film received such prominent coverage. And the government finally gave credit to the movement and many films went on the win prizes in those prestigious festivals in the first half of the 1990s.

AC: What were the social and political repercussions of being this direct with a tumultuous historical past?

PC: The film prize and its focus on the 228 incident in 1947 raised audience's interests and resulted in a record breaking box-office. The political incident was a taboo for years. In fact, I heard whisper of the incident only after I came to Austin to study. The film came after the lifting of the martial law and suddenly it was ok to talk about it. The film team did some thorough research, using the fate of a family to explore the historical impact. Watching the film became a must for a history lesson for the local Taiwanese.

Oddly enough, people have different and contradictory readings. Some interpreted the film as an attempt to absolve the ruling party's crime of persecuting dissidents; the others thought the film upheld the Taiwan independent movement. It really upset the director. I heard him shouting at one opinionated audience on the street of Berlin: "If you don't like my treatment of the political issue, go make your own film".

For several years Taiwan screens were full of films with political content. People became obsessive with political debates ever since. And the upshot? audiences were fed up with political films.

AC: The past seems to allow Hou a greater semblance of plot, shaping threads that otherwise wouldn’t be there. With his contemporary works, forgoing the discernable political backdrop makes for a looser, more liberating cinema. This series, and Hou’s oeuvre, is so contextualized within Taiwanese history and its culture. What is there to obtain from his cinema for those that may lack the historical background needed for a greater understanding?

PC: Hou's early films are invariably about growing up - the struggle of youngsters to survive under economic pressure and the expectation of an upcoming affluent society. His films made after the lifting martial law were more obsessed with the island's political past and its impact on people's life. One really does not need to go deep with the political details to appreciate his subtle and poetic ways to construct narratives and his beautiful mise-en-scene. His later films eschewed the political contents and adopted a freer, confident style and somehow, I think it's more difficult than the earlier films. But people learned to appreciate his long takes, Rembrandt-like low lighting, elliptical narratives, etc.

AC: Sometimes, with foreign cinema, people cling onto the notion of “universality,” particularly with a film like Edward Yang’s Yi Yi. Do you see this as a reductive perspective, a slight attempt from the viewer to engage with work that’s asking for a lot more?

PC: Edward Yang was different. He was a film philosopher. His films are about urbanity, international society, and the essence of life, etc. He thought about those things with his images. In that sense, he raised the threshold not according to national border, but aesthetics and philosophy.

AC: City of Sadness feels like the dominant turning point for Hou’s more elliptical approach to storytelling. What formal tactics are presented here that would go onto become synonymous with his post-City sensibility?

PC: Obsession with preserving realism with long takes, long shots, natural lighting, real locations, elliptical editing, poetic captions, the expansion of space via off screen sounds, etc. Sometimes, he could go extreme by using plain-sequence all through one film, like Flower of Shanghai, only a dozen shots in the entire film.

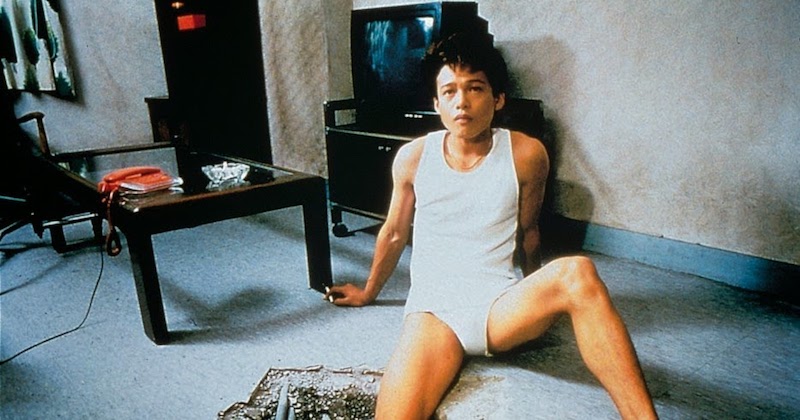

AC: Your films, most notably Tsai Ming-liang’s The Hole, seem indebted to the work of Hou. Even looking at filmmakers outside of Taiwan, such as Hirokazu Koreeda, you find an aesthetic touch that echoes him. How vital has his influence been over his thirty-plus year career?

PC: Tsai Ming-liang is more indebted to Francois Truffaut and Rainer Werner Fassbinder than Hou Hsian-hsien. In The Hole, I practically forced him to put musical episodes in the narratives. I asked my best friend Lo Manfei to choreograph the musical parts. I thought it created an irony, juxtaposing reality and fantasy, colorful visuals and dire surroundings, song and dance and silence, hedonism and pessimism. Tsai refused it originally. but learned that people like it and went on exploiting the format in several films.

Kore-eda was a real fan of Hou and Yang. He made documentaries on these 2 for NHK TV before he became a feature film director. His Mabrosi reveals a deep-rooted sensitivity similar to that of Hou. Later on, his films showed more of a Yang influence. But he has transcended this stage and developed his own style in recent years. I think he is a true master now. However, Hou remains a big inspiration to many Asian directors. I think there is a sentiment that passes down from Ozu, Naruse, that people in this part of the world feel intimate to.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

June 28, 2019

AFS Cinema, Austin Asian-American Film Festival, Peggy Chiao, Hou Hsiao-hsien, A City of Sadness