Lit-urday: Spinster: Making a Life of One's Own

All the single ladies: Edna, Edith, Neith, Maeve, Char ... and Kate

By Kimberley Jones, 11:00AM, Sat. May 16, 2015

It's been a long week, and now you deserve to have one day when you can curl up with a good book – let's call it Lit-urday. Here's a book that takes a dirty word – spinster – and spins rousing new meaning from it.

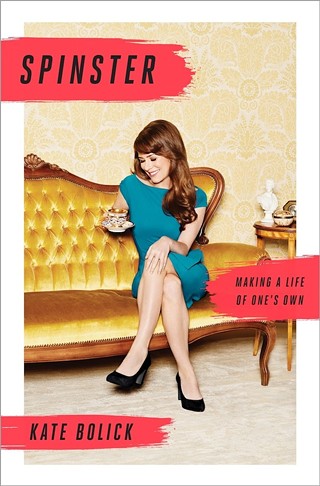

Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own

by Kate Bolick

Crown, 336 pp., $26

In 2011, Kate Bolick’s cover story for the Atlantic, “All the Single Ladies,” was a flare gun in the night for a generation of women driving blind, those of us for whom our mothers’ roadmap to personhood – which so often involved marriage – no longer made sense. It was the rare mainstream media piece to consider this seismic shift in marriage expectations without treating it like a condition that needed a ladies mag prescription: meaning, how to get the right guy, or when to know to settle for the just-alright one.

Bolick’s book-length expansion on the subject, Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own, circles the same subject, but cinches its focus for an intensely personal memoir mixed with literary biography. I missed the potency of Bolick’s original piece – its broad application, its examination of communities outside her own – but this explicitly individual version of singledom opens up some surprising byways in the process.

Bolick organizes and intertwines her professional and personal history with the examples of five prominent single women, all writers, whom she calls her “awakeners." They include Irish fiction writer and New Yorker essayist Maeve Brennan; the columnist Neith Boyce, who, in an 1898 column for Vogue, planted a sprightly flag: “I never shall be an old maid, because I have elected to be a Girl Bachelor”; the poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, whose unapologetic, catholic sexual appetites lead Bolick "through those early, confusing years of sex as a single person"; the novelist Edith Wharton; and Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Not all of these women stayed single – Gilman, for instance, was twice married and wrote the semi-autobiographical "The Yellow Wallpaper" after her own bout with postpartum depression. But in the unique and overlapping stories of each of these women, Bolick forges sincerely felt relationships with her awakeners and finds consistently interesting ways of chewing over issues in her own life. Who knows how much of the order of these awakenings has been finessed to create a narrative arc, but Spinster is fascinating as a document of how books can help shape and frame our own experiences. Or, to get more mystical about it: A book has to find you at the right time.

Spinster isn’t just the story of one woman’s wrangling with what it means to be unattached. It’s also about a writer considering what she needs to do to master her craft.

“You are all your work has. It has nobody else and never had anybody else. If you deny it hands and a voice, it will continue as it is, alive, but speechless and without hands. You know it has eyes and can see you, and you know how hopefully it watches you.”

(As someone who grinds teeth and invents 100 other things to do than confront the blank screen and blinking cursor, that struck me as a rather radical – so wonderfully unpunishing – way of thinking about the writer’s relationship to her art.)

Occasionally, Bolick's prose tips a little too goddessy frou-frou. (Some critics have sneered at the term "awakeners," but it's worth noting she's borrowed it from Edith Wharton.) And while, by framing her observations in the first-person, she's built-in a handy escape clause, some conclusions still rub wrong. For instance:

“Here in the year 2000, the future itself, men were still expected to be breadwinners and providers. No matter how hot my ambitions burned, I always knew, deep down, that if I couldn’t make it as a writer, and if I failed to find my way in the working world, I could create personal meaning and social validation through getting married and having children. I had an escape hatch; men didn’t.”

I question whether this was still true when the 20th century turned over into the 21st, and point out that Bolick has the luxury of feeling certain of marriage and motherhood as soft-landing, standing options; her middle class background, her race, and her attractiveness all play a part in that feeling of personal security. (Notably, her good looks have been used to promote the book, and original Atlantic piece, both of which place her on the cover.) I’m not sure Bolick realizes this confidence is specific to her and not a universal given.

I broke into more than few mental arguments with the book, not unenjoyably. Spinster is a lively, pleasurably windy, and well-researched book. (Her asides tease whole other books to be written, as in a paragraph about a group of post-Civil War “radical spinsters” who petitioned the Massachusetts State Legislature to give them their own village; they argued that since the decimated male population meant they likely couldn't marry, the state should provide what a husband could not.) If Bolick's insertion of herself into the literary biography stretches occasionally whiffs of a Carrie Bradshaw-like "I wonder…," Bolick does so at some risk. She exposes a lot, and she's not always giving us her best angle. By the end, it feels ungenerous to smirk at the tiny fumbles. The neatest trick of the book may be how it takes a seemingly dead-end concept – the spinster, a word that implies finality – and reworks it into a story about possibilities. It's not a roadmap; it's a trail of crumbs tracing how one woman got closer to figuring out who she wants to be.

A note to readers: Bold and uncensored, The Austin Chronicle has been Austin’s independent news source for over 40 years, expressing the community’s political and environmental concerns and supporting its active cultural scene. Now more than ever, we need your support to continue supplying Austin with independent, free press. If real news is important to you, please consider making a donation of $5, $10 or whatever you can afford, to help keep our journalism on stands.

June 6, 2025

June 6, 2025

Kate Bolick, Spinster, Making a Life of One's Own, feminist theory, literary biography, All the Single Ladies, Edith Wharton, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Neith Boyce, Maeve Brennan, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Girl Bachelor