You Are Here

Postcards from the 2008 Texas Book Festival

Fri., Nov. 7, 2008

Reassessing America, With grim Conclusions

With every major politician busy on the campaign trail, the expectation was that this year's Texas Book Festival would be light on election discussion. Instead, in the midst of a partisan vs. partisan year, there was debate of what America is and where it stands in the world.

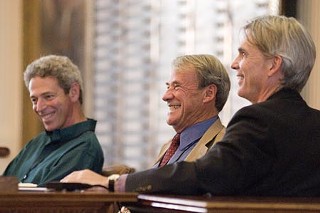

Before starting Saturday's panel on electoral politics titled America – United We Stand?, UT professor and documentarian Paul Stekler recalled the recent passing of one of the greatest chroniclers of American life, Studs Terkel, and the time Stekler almost killed him. Fourteen years ago, on an icy day and even icier roads, they were driving through Chicago. Terkel kept distracting Stekler's driving by pointing at some hole-in-the-wall bar, saying, "Al Capone used to drink there." Stekler was convinced that the papers next day would read "PBS Crew Kills America's Most Popular Storyteller." Panelist Ronald Brownstein, author of The Second Civil War, then went on to argue that political parties and internal migration are separating Terkel's "great melting pot" of America into spheres of influence.

There could have been awkwardness on the War Over American Ideals panel, with Fred Burton, former deputy chief of the Diplomatic Security Service, who helped establish the original pre-9/11 rendition program, and The New Yorker staff writer Jane Mayer (whose book The Dark Side explores post-9/11 rendition) sitting side by side. Instead, there was some consensus. Both argued that Guantánamo Bay should be closed (Burton for operational reasons, Mayer for moral and political reasons), and both criticized the public acceptance of how the war on terror is waged.

The fear of an all-powerful executive also came to the fore. As he read from his book The Challenge: Hamdan v. Rumsfeld and the Fight Over Presidential Power, Jonathan Mahler noted that detainees in the war on terror were being tried in courts set up by President Bush, clearly violating the separation of powers between judiciary and executive. That fear was echoed by Jeremy Scahill, author of Blackwater: The Rise of the World's Most Powerful Mercenary Army, who warned that the "private security firm" has been deployed on U.S. soil by the president. Cheerful stuff. – Richard Whittaker

A Place for 'Place,' Be It the Hour, Era, or House You Grew Up In

"Imagine post-World War II 1950. Put yourself there," said David Hajdu, author of The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America. "The goal was to be a chiseled man with a pretty, blond wife. And in comic books, married people are miserable. They knock each other off in the first three pages."

The collection of pop-culture scholars gathered in the Capitol's Extension Room last Sunday just laughed at comic books' early attempts to undermine the American ideal of matrimony. (And they also laughed at an anti-comic-book film depicting the horrors of children mad with reading rage, which aired on a newsmagazine-style program in 1955.) But for the families, authors, and illustrators who lived through that period of McCarthyism, the threats were very real. Hajdu's book offers a new lens through which to view America's midcentury social atmosphere and how it affected the publishing industry in much the same way it affected the film industry. Through a collection of newspaper clippings, photographs, television shorts, and comic-book leafs, Hajdu captures a specific time and place – contextualizing the stories and personal anecdotes present in his book, as well as the comic-book narratives and illustrations of the day.

Shannon McKenna Schmidt, another Sunday panelist and the author of the literary travel guide Novel Destinations: Literary Landmarks From Jane Austen's Bath to Ernest Hemingway's Key West, shares an interest similar to Hajdu's in recapturing the time and place associated with artistic creation. Taking the theme a step further, her book not only presents the historical significance of literary locales but demonstrates how an author's fictional setting remains intrinsically tied to his or her real-life sense of place, as with, for instance, Louisa May Alcott's Orchard House in Massachusetts. "The Orchard House is a wonderful place because it's really the closest you can get to walking through the pages of a book," said Schmidt. "The reason for this is because Alcott drew so heavily on the house and her family, and visiting fans of [Little Women] will no doubt recognize the trunk of costumes the March sisters used to stage their plays." – Ashley Moreno

Defusing the Writer's Myth

Once upon a time, it was not permitted for the common person to hear services of worship in his own language, to read or understand scripture for him- or herself. Those days are long gone, of course, although similar principles prevail among certain lawyers, cosmeticians, plumbers, and loan sharks who would have you believe you are entirely incapable of doing fill-in-the-blank yourself.

At the Texas Book Festival, a handful of panels that explored writers' practices summarily dismissed the idea that their process belongs to an exalted few, extolling instead the virtues of simple, stubborn persistence. At two panels, Character-Driven Fiction and Writers on Reading (presented by publisher Vintage/Anchor), literary stalwarts such as Francine Prose (nominee for the National Book Award) and Ann Packer (The Dive From Clausen's Pier) laid plain the doubt and consternation that they encounter daily. In the words of Andrew Sean Greer (The Story of a Marriage): "We'd like you to think we're transcribing the voice of some angel up above, but nothing could be further from the truth. It's hard work." These authors attested time and again that they are like wanderers stumbling in the dark, guided by dim forms of character and setting that lead them in constant uncertainty, skepticism even, to an eventual, hopeful resolution. In the best case, said Carmen Tafolla (The Holy Tortilla and a Pot of Beans) at Saturday's Evoking a Sense of Place panel, a writer "let[s] the characters invent themselves."

There's an irony there, that an author faces such discomfort and ambiguity in order to produce a piece of art that will make the reader feel solid and reassured in its embrace. But this contradiction is key to the process, according to Packer, who said, "To write without knowing is terrifying and necessary." No less an authority than Prose revealed, "It's not until the last sentence, the last word on the last page, that I know I won't have to tear up the whole draft – that it works." Humble words from one so prolific. They discover through the writing itself, it seems, whether a character will turn out to be believable, whether the action in a story will come together in a meaningful way – whether the train they follow leads anywhere at all. – Elizabeth Jackson

After Hours With Richard Price

Writing – there's little profit in it. Certainly as a career choice, it must rank beside that of stained-glass-window fitter, above that of town crier. Or as Richard Price explained Saturday evening, recounting his decision to study creative writing rather than entering law school, "Even today, I'm still trying to prove I'm responsible to my parents – one of who's dead and the other who's out of her mind."

Price, the author of eight novels (most recently, Lush Life) and a number of film and TV screenplays (including The Wire), was speaking at the Continental Club with Philip Gourevitch (editor of The Paris Review). The two discussed the craft of writing for almost 40 minutes, loosely following a format first laid down in The Paris Review a half-century ago. A series of recently published books, The Paris Review Interviews, collects the best of the famed literary quarterly's author interviews, with Price making an appearance in the first volume.

As an interview subject, Price is scabrous, witty, and generous – and quite unafraid of revealing his creative neuroses. Also, at least when it comes to being asked whether he considers himself a writer of genre fiction (several of his novels have been constructed around police procedures), just a little tetchy. "Let me ask," he says. "Is Cormac McCarthy a cowboy writer? Genre writing is the triumph of plot over character. I don't care 'who did it.' I'm more interested in when good things happen to bad people." – John Davidson

For more Texas Book Festival coverage, see the Chronicle Books blog at austinchronicle.com/underthecovers.