My Slammer Vacation

How I Spent...

By Phil West, Fri., Sept. 5, 1997

|

|

For the Austin team (Coach Mike Henry, Genevieve Van Cleve, Susan B.A. Somers-Willett, Wammo, and myself) the actual competition could have left us with a bittersweet taste if we let it. In our first night of competition, we lost a close match to the San Francisco team, which eschewed the number-crunching and strategy in which other teams (including ourselves) were schooled in favor of just sending out great work and seeing what it did. What they did was beat us by a fraction of a point. As it turned out, though, we were still very much in control of our destiny, and used our underdog status as a motivating tool to fight valiantly and win our other two bouts. The rankings we earned were respectable -- we finished seventh out of 33 teams, and were grouped alongside a number of fine teams that almost made it to the Final Four. But the respect we earned was even more rewarding; through it all, we remained humorous, gracious, gregarious, and, of course, the team other teams sought when they wanted to take in a late-night hotel party.

It was on a rooftop in New York City the Sunday before the competition, taking in the surreal, lit-against-darkness face of the World Trade Center, that I had the revelation about why I love slam poetry so much. It's the vehicle that has allowed me to take my poetry, and the city I love, to audiences across the country. I never expected to be reading work in Middletown when I started this journey, but here we were: five poets from Texas set loose across the Northeast. This is how we left our mark. Saturday, Aug. 2: Shawn and Lana from the Rude Mechanicals theatre group were positively diabolical at our send-off party the night before, buying multiple Jagermeister shots for the team as the Wannabes played. Strangely, we're not hung over as we stagger awake that morning, and board a TWA to St. Louis at full animated chatter. We descend on one of the smoking prisons at the St. Louis airport and do a premeditated act of poetry terrorism, performing our group piece "Personal Ads" to the group of unwitting smokers. We have a captive audience, and those who aren't completely baffled get into it once they realize what we're doing. Later, in the bar, all of us but Wammo disappear, leaving him next to a thick-necked, mustachioed guy who has been yelling at the TV during the NASCAR race ("C'mon! Let's go! Ram his ass!"). The guy turns to Wammo and asks, "So, you all got your own band going?" Wammo turns to him and deadpans, "Yeah. We're the Melvins." He asks what kind of music it is, and Wammo says, making the devil horns sign with his hand, "Metal."

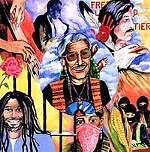

In New York that night, we drop our bags at the home of Ron English, a brilliant painter who first made his mark in Austin, and is now making visual commentary mixing and matching a variety of styles -- my personal favorite being a recasting of Picasso's "Guernica" with cartoon characters. Imagine an angular, distraught Sylvester cradling a dead Tweety in his arms and you begin to get an idea of the eerie jocularity in his work. Later that night, we perform at the Knitting Factory with our friends from the Albuquerque team. It's the first time we see the influence of Danny Solis, from last year's Final Four Austin team, on the Burque poets. Clearly, they're hitting hard and they're well-schooled. They were great poets to start with, and now, under Solis, they've learned the science of slam. That night's den of hedonism: the Raccoon Lodge, a biker bar with both Ted Nugent and Barry White on the jukebox. Open

'til 4. We stay 'til 5.

Sunday, Aug. 3: An off- day for us. Gen and I go to the Keith Haring retrospective at the Whitney Museum. It's a staggering show. There's much documentation on his early work with chalk drawings in the New York City subways and his subsequent arrests for "defacing" the tunnels with spontaneous public art. Haring embraced pop culture and celebrity so readily that, sometimes, it's hard to remember just how political he was. Yet the mere fact that he died of AIDS-related illnesses at age 31, had the courage to reveal his condition to the media at a time when that was virtually unheard of, and then kept working until the end is powerfully political in itself. If you're in New York in the next few months, know that this show gets a big stamp of approval from Team Austin.

Monday, Aug. 4: We awake from the rooftop where we've slept, get the traditional giant rental car, and head to Boston. Two instrumental people in the slam community, Michael Brown and Patricia Smith, have organized a 10-team head-to-head slam there and we go to watch and take notes. Since we'll be in the thick of it in two days, we welcome the chance to enjoy poetry without the pressure of performing and competing for one night, and we see amazing things. The Swedish team are crowd darlings, especially Bob Hansson, who transcends language with a manic performance style that moves him into the crowd and to all corners of the stage. Boston beats Sweden and L.A. in the team finals and L.A.'s Jerry Quickley, a big, smiling guy with a booming voice, an afro, and cool yellow glasses, takes the indie finals with a series of fast-moving tales about urban life. Taking a page from the Jerky Boys at the after-slam party, he coins what becomes one of our catch-phrases for the week: "I'll see you tomorrow with my bag of rhymes, fuckface!" We say this to each other until there's nothing but inferior beer left. Tuesday, Aug. 5: On the Massachusetts-Rhode Island border, we see a Big K Mart. That's what it's called: Big K Mart. Thrilled, we spill out of the car and get, among other supplies, the bungee cords allowing us to finally strap the cow horns on the Austin car. We drive through Middletown to get to the hotel, and if Poetry Summer Camp didn't start in earnest the night before in Boston, it's officially started now. We begin pointing out some of the people we've been telling Susan about for the past few months. We try to find our venue for the first night's competition and troll the streets of Middletown for an hour, finally enlisting help from a policeman. "Are you sure that's where it is?" we ask him once he gives the seemingly improbable directions. By the time we get there, the featured reading is over and poets are trying to be heard at the open mike over the din of poets chatting with one another. The venue is a sports bar called the Dugout with big wooden pillars blocking some of the sightlines. There is no stage. It's a room where we can move about fairly freely and where Wammo, as a loud poet, can be heard without a mike. It's a room where we can go over the top. We note this for our bout.

Wednesday, Aug. 6: Opening ceremonies, in the past, have involved teams doing introductory pieces. The organizers have eschewed this practice this year, plus it's a narrow room, and many of the poets still haven't seen one another yet, so while introductory speeches and poems from hosts and slam dignitaries go on inside, many of the poets stay outside and smoke cigarettes and greet each other. Tarin Towers from the San Francisco team sees me, gives me a mischievous grin, and says, "Juliette Torrez [co-director of next year's slam and one of Team Austin's best friends] told me you were trying to get dirt on our team." I feign innocence, badly, but we laugh about it, for the rivalries are friendly and the competition is a way to get the most out of poets. Especially when it's teams like San Francisco and the Ozarks, for our paths cross from poetry festival to organizing meetings to group e-mailings throughout the year.

Several hours later, though, we are feeling the strange shock of getting a 2 in our first night of competition. The draw and the order of poets are pretty much what we had counted on. I opened with "Divorced Guy," Lisa Martinovic from the Ozarks followed me, which was a bit of a surprise, and then Nancy Depper from San Francisco came up, and at the end of one round, we were down one-tenth of a point to the other two teams -- not a bad spot to be in. Our duet between Genevieve and Susan closed the second round, was performed brilliantly, and gave us a lead, but we lost half a point on a time penalty for going a mere second over time. In the third round, we figured that Wammo's loud, manic, alpha male energy would be the perfect counter to the long line of lyrical poetry that had proceeded him. After all, since I'd gone up first, there had been six slots in a row filled by women poets, and we'd expected that there would be women saved for the end. But now, even with more women than men competing in our bout, it would be just Genevieve and three men after this. Wammo, however, bombed -- not because of performance, but because the judges perceived us as too much about performance and loved the lyrical. We were down to S.F. by three-tenths of a point at the end of round three, and that's where we stayed. Final score: SF 105.7, Austin 105.4, Ozarks 105.3. A great night of poetry, and scores so close to each other that we should all be winners, but, alas, we're not.

Several hours later, though, we are feeling the strange shock of getting a 2 in our first night of competition. The draw and the order of poets are pretty much what we had counted on. I opened with "Divorced Guy," Lisa Martinovic from the Ozarks followed me, which was a bit of a surprise, and then Nancy Depper from San Francisco came up, and at the end of one round, we were down one-tenth of a point to the other two teams -- not a bad spot to be in. Our duet between Genevieve and Susan closed the second round, was performed brilliantly, and gave us a lead, but we lost half a point on a time penalty for going a mere second over time. In the third round, we figured that Wammo's loud, manic, alpha male energy would be the perfect counter to the long line of lyrical poetry that had proceeded him. After all, since I'd gone up first, there had been six slots in a row filled by women poets, and we'd expected that there would be women saved for the end. But now, even with more women than men competing in our bout, it would be just Genevieve and three men after this. Wammo, however, bombed -- not because of performance, but because the judges perceived us as too much about performance and loved the lyrical. We were down to S.F. by three-tenths of a point at the end of round three, and that's where we stayed. Final score: SF 105.7, Austin 105.4, Ozarks 105.3. A great night of poetry, and scores so close to each other that we should all be winners, but, alas, we're not.

Later that night, we spearhead a party in the hospitality room across from our hotel room. It spirals out of control, and one fire department and one police department visit later, the staff at the Holiday Inn begins to reevaluate their collective wisdom in deciding to let the poets stay. The next morning, Wammo will overhear some of them talking.

"How old are they anyway?"

"College-age and older."

"Gee, you think they would have grown up and gotten real jobs by now."

Thursday, Aug. 7: In the restaurant that morning, the founder of the poetry slam, Marc Smith, talks to Wammo and observes, "Looks like the Slam Poetry Gods bit you on the ass last night. It's about time it happened to you." Wammo spends much of the day shaking hands with people and saying, "Hi, I'm Wammo. I suck. This town hates me." But when I hear that a lot of the teams who won their Wednesday bouts are going up against each other tonight, and there will be no more than five teams with two 1 rankings by the end of the night, this gives us renewed hope. In the afternoon, we have a long strategy session with the Albuquerque team and set our orders. We're up against Providence and Chico, two steady teams with a lot of group pieces in their arsenals, and Albuquerque has the spunky Montreal team and the Mouth Almighty juggernaut to contend with.

We win our bout in a crowded restaurant sending Wammo first with "Too Much Light," Gen second with "Ladies First," "Personal Ads" third, and Susan's stunning, political "A Woman In Texas," which we run as a trio with Gen and I joining Susan, as our final piece. We win handily, and Wammo gets the high indie score of the night -- and indication that the slam gods have declamped themselves from the mighty ass of our team berserker. We receive the news that Mouth Almighty beat Albuquerque, which gets us a bit down, and return to the Dugout where semi-finals matchups are being passed around. With a 2 and a 1, we're guaranteed to break into the 18-team Friday night competition, but it's not until we see our ranking that we realize the strange serendipity of this year's slam: We're up against Dallas, who, with wins their first two nights, need just another win to make it to their first finals. We're also up against Los Feliz/Silver Lake, a dangerous team with two powerful, political poets of color. And we're in the same room with Albuquerque on Friday, facing two of Danny's former teams, Boston and Asheville. The rankings depend on point totals, which vary wildly from venue to venue, but clearly, there's some kind of higher power at work here, and it's got an incredible sense of drama. Or humor.

Friday, Aug. 8: The exhaus- tion is beginning to set in for me. It's good that no one knows where the annual softball game is, because I would feel compelled to go, and it would be a mistake. After another strategy session with Albuquerque, I do the one thing I've been looking forward to aside from competition: the head-to-head haiku slam. Sixteen competitors don red or white headbands and take turns reading haikus. They range from the esoteric to the highly political to newcomers counting on their fingers, but my favorites are in my camp: crass. Despite brilliant efforts from Jeff Meyers (I miss my girlfriend/but with each passing moment/my aim gets better) and Jerry Quickley (I guess you know me/by my prison name, which of/course is Otis' bitch), they're out in the first round. But from my opening salvo, "A Case Made for Tighty Whiteys Haiku" (Boxers don't flatter/my package like the white briefs/do, in the black light), I'm off to the races. I only bog down in the finals, where Debra from the L.A. contingent is throwing lyrical haikus against my dwindling pile of masturbation and game show host references. I lose, but crowd members are quoting my stuff back to me, and I feel like a minor celebrity.

We go to the bagel shop for the semi-finals. That's right. The Manhattan Bagel Cafe. Imagine slamming at Bruegger's, and you have it exactly. It actually turns out to have a lot of energy, and with the lineup there, it's packed. Wammo gets us a lead in the first round, and in the second round, I go up with "Response," better known as my high school reunion piece. Two-thirds of the way through, the unthinkable happens. I've been hitting the piece harder than I ever have in my life, the crowd is with me, I'm readying to round the home stretch, I lose a bit of rhythm on a line, and the piece leaves my memory. Foomp. It's just sucked out of my head, and for six seconds, I can't get a handle on my signature piece, and stand there searching my brain wildly while trying to keep game face. Finally, I find a line, essentially the last line, jump there, take the applause as I go back to my bench, and meet the sympathetic eyes of my teammates. Then the scores come up: A 27.7. I win the second round. Our lead increases to four points.

We go on to win, with Gen closing on a powerful version of "Letter to Aldon," (aka the abortion poem) which has at least four members of the audience crying halfway through it. It's beautiful to watch. Los Feliz/Silver Lake, whose Yvonne de la Vega and Ben Porter Lewis shine brilliantly in back-to-back poems, takes second. Dallas finishes third. We all stay for the Boston-Albuquerque-Asheville matchup, and it turns out to be absolutely monumental. Boston's Lisa King, in the final round, does an icy, haunting version of her anti-Republican AIDS policy poem "Bring Them Back," and needing a 29.7 to win, Albuquerque closes out the night with "Bullet in the Head," a Kenn Rodriguez piece turned into a rhythmic, heavily interwoven quartet. The structure is simple, with a lot of repetitions of phrases and functional choruses, but there are breaks into controlled chaos. It's like a noise rock song, only it's a gutsy political piece as well. 29.8. Albuquerque knocks Boston out of the finals and later rejoices when news comes that Chicago beat Mouth Almighty in their semi-finals bout. The irony will come later: had Mouth Almighty beat Chicago, Albuquerque would have edged into the finals. As things develop throughout Middletown, Burque will finish a close fifth, with L.A., us, and Boston straggling behind, a mere fraction of a point behind one another.

At the hotel that night, they've moved the hospitality room to the first floor, but the poets are more interested in the bar, and then the pool. Wammo is the first to jump in with all his clothes, and then the momentum swings toward the pool. Those who jump in chant the names of various onlookers until they jump in. After filmmaker Paul Devlin sneaks in nude, I quickly jettison my clothes and make a dramatic entrance. Thirty poets in the pool later, and the hotel staff is completely perplexed. We can be heard chanting throughout the entire hotel. We seem to outnumber everyone. We are an unstoppable force. We drink 'til dawn. We don't have to perform the next day, after all.

Saturday, Aug. 9: Finals day. This traditionally starts with the Slammasters meeting, where controversy usually crops up. This time, it's with the Mouth Almighty team, who are already meeting with controversy because people perceive them as a hand-picked team engineered to win the competition through domineering talent and attitude. Sort of the Dallas Cowboys of the slam poetry world. (Wammo was asked to try out for the team early in their selection process, by the way, but refused in favor of staying true to his hometown.) In their semi-finals bout, they used the end of a belt to mime a penis during a quartet about sex, which is a clear violation of the no-props rule. Yet there's no penalty in the slam rules for breaking this rule, so about 80 poets -- those awake enough and invested enough to be in the room -- are trying to decide the team's fate while the team sits in silence and a certain degree of disbelief. One loose cannon, the coach of the Montreal team who has, according to a team member, abandoned them early in the week, motions for a vote to disqualify them from the finals, which seems a highly punitive, dangerous, and just plain stupid move. Faith Vicinanza, who is running this year's Nationals, rules that she doesn't want to do anything about the violation. As someone who will be in her spot next year, I'm wholeheartedly inclined to agree, even though I think that we can't retroactively punish Mouth Almighty, need to learn from this incident, and give the rule teeth for the finals tonight and then for next year. We finally vote to keep them in, set down the penalties for the finals, and move on. The room has inflated with tension and deflated again. There's still traces of it there, but it subsides as we move on to happier topics of business, including Austin '98. We get a list of inspired suggestions.

For finals, we decide to dress up. Just before opening ceremonies, we had hit on the idea of dressing as beauty queens; once we learned of the Wal-Mart near the hotel, we knew we'd be able to pull this off. So Susan and Wammo rounded up plastic tiaras and ribbons to use as sashes. Drawing on one of my latest poems, I became Miss Look At My Ass. Gen was Miss Worst Feminist, relying on an earlier poem for her nom de beauty. Susan turned to our favorite T-shirt of hers to be Miss That Slut Girl. Mike was Miss Guided. Wammo was Miss Fuck Off. We strode into the athletic fieldhouse where finals were being held doing the elbow-elbow-wrist-wrist-wrist wave. We were an instant hit. Anxieties that poets had about the athletic fieldhouse -- which at first, appeared to be an large, echoey barn, but got better as the show continued -- melted away as they saw us reveling in the communal Puckish spirit that was dominating our chemistry that week.

At the after-finals party, after Mouth Almighty won the team finals and Cleveland's outstanding Boogie Man took individual finals honors (the first man, incidentally, to do so), we got the chance to play the heroes. Earlier in the day, the organizers announced that the party was BYOB. Wammo immediately sprung into action and took up a keg collection. As matters developed, the kegs turned into 510 beers, loaded in the back of the car just before finals. The car rode considerably lower than it had all week, and when we arrived at the party brandishing 30-packs for the crowd, we achieved a new heroic status.

Sunday, Aug. 10: Traditionally, this is the day of farewells and hugs and photo ops, but Saturday's party went so late, not even counting the skinny-dipping and one-last-chance-to-scare-the-hotel-staff components of the evening, that by the time we awoke on Sunday afternoon, it was just us and Albuquerque and a few stragglers from the Montreal team. Mike, Wammo, and Danny even got kicked out of the pool late Sunday night because the hotel staff, at that point, could. The hotel had already slipped back into a normal routine -- quiet by 10 in the evening, the sounds of lite Muzak replacing the charged tones of poets finding like-minded observers, the halls strangely absent of people and the energy and exuberance of the past few days. Middletown and its environs were returning to normal. Hopefully, we had made some impact on them, some impressionable change about how exciting poetry can be to audiences and especially its proponents. We gave until we didn't think we could give, and then we gave some more. Next year, the audiences are here, and knowing Austin audiences and how the poets feed off audience, the poets are going to surprise themselves. Great things will happen.