Rebuild the Guild

Michael Yates and his fellow artisans bring new life to Austin's cadre of craft

By Wayne Alan Brenner, Fri., Oct. 7, 2011

Michael Yates of the Guild of Austin Artisans is building a coffin for his grandmother. She's the one who commissioned it.

"She asked me specifically, over Christmas cookies, a year and a half ago," he says. "I haven't made it yet, but it's been a really different design process. Obviously, it's more sentimental to make than most things. It's also a more intense thing for someone to buy. Luckily, there's no urgency – there hasn't been any urgency – for her getting this casket."

Luckily, first, because that means grandma is still alive and kicking.

"She's in good health," affirms Yates, smiling. "She's 80 and a half, and her mother – my great-grandmother – lives right next door, and she just had her 100th birthday party. She's not as on board with the whole coffin-building idea as grandmother is."

And luckily, second, because Yates, a custom woodworker, needs to take his time to do it right. The things he more often makes – dressers, shelves, credenzas – are works of creation that blur the divisions between craft and art, relying on the artisan's hard-earned skills and knowledge of materials and sense of design for their strength and beauty.

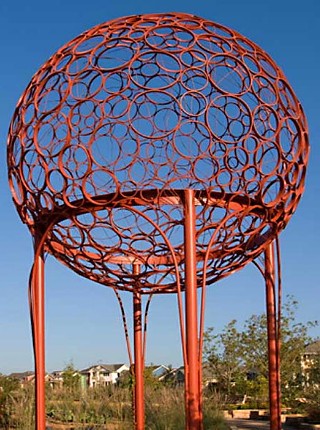

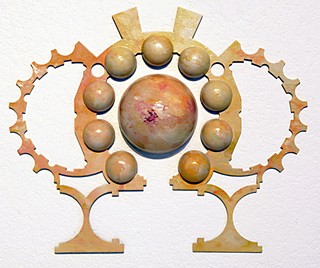

Strength and beauty are basic requirements for architectural elements, and the abetting of architecture is the sort of work Yates focuses on. It's the sort of work, in fact, that the entire Guild of Austin Artisans – formerly the Architectural Artisans Collabor-ative – focuses on. Consider: Judd Graham of 220 Designs, creating pivoting panels of steel and willow for Fino restaurant; Hawkeye Glenn of Blacksmith Industries working steel and concrete to render R. Murray Lege's design for the fingerprint labyrinth at the East Austin Police Substation; the bright storm drain tiles embedded in Austin sidewalks, courtesy of the unharried potters at Clayworks Studio/Gallery.

"The example I use," says Yates, "is that there are people in the guild who work in glass. But if you're a glass artist who's just blowing bongs, that's not our guild, you know? That's a different guild. Whatever people work with in our guild is architecturally based."

So why the name change?

"Well," says Yates, "people felt that the old name was a little clunky."

There's also a new website and an exhibition – the guild's first in more than four years – at the Commodore Perry Estate across from the Hancock Center.

"The gentleman who bought the estate was there during the [Heritage Society of Austin's] homes tour in the spring," says Yates. "And he's into artisan craft of all kinds – there are some fantastic examples of it in the estate, like metalwork and sculpture, carved stone – so he was all for us having our exhibition there. And they're refurbishing the place, the whole 10 acres, starting with the mansion. It's gonna be a regular event center – and we're the first event. We'll be using the ground floor of the main house and the patio."

That's work from two dozen woodsmiths, concrete artisans, metalsmiths, ceramicists, glassblowers, and sculptors. That's work from people who take the raw materials this world offers and turn them into objects both functional and fantastic. Consider: Susan Wallace's aluminum grillwork for the doors at HausBar Farms and Ford House Farm, Chris Levack's shade trellises at Whole Foods Market, Blue Genie Art Industries' rendition of Michael O'Brien's immense relief panels on the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum. This isn't work by weekend dabblers; this is the result of much training, much effort, and more hours of industry per day than most people spend watching whatever's in their weekly Netflix queues.

Austin Chronicle: What makes a person choose the artisan's life in the first place?

Michael Yates: Well, for me, I was studying engineering at [Texas] A&M, and I stumbled onto this student center workshop. You have to take some rudimentary safety tests and pay a fee, and then you can basically go nuts in the shop. They cut me loose in there, and I made something, and it was a very, uh, beyond satisfying process. Then I finished my degree and worked in engineering for a few years and did a couple of projects in wood. Then I quit my job and started doing woodwork full-time.

AC: But why wood, specifically? Unless you had a premonition that your grandmother would want you to make her a coffin ....

MY: Well, it wasn't a student welding shop that I lucked into; it was a wood shop – and I'm grateful for that. And shortly after I built that first piece, I did a study abroad, a language program in Japan, and Japan is one of the two greatest woodworking cultures on the planet.

AC: What's the other one?

MY: Scandinavia. But I was in Japan for three months, and I saw the best, the oldest temple construction in wood in the world. I saw how good it could be, so I came back and made a couple things for people in my spare time, then started doing it full-time sooner than I really had any business to. Looking back, if I was my parent, I would've been like, "That's pretty stupid."

AC: Were your own parents supportive?

MY: Oh, totally. But when I was saying I wanted to be a woodworker, my father kept reminding me that it's a really hard way to make a living. His father was a carpenter. And it is a hard way to make a living.

AC: And yet you are, in a pretty rough economy. How do you ...?

MY: Well, my clients are one of a few mentalities that are willing to save up to buy a thing once that they'll never have to buy again. As opposed to the buy-and-throw-away-and-buy-again-in-five-years technique, y'know? Because, in the long term, I'm not expensive. Apples to apples, in the store, my stuff – most of the guild's stuff – is expensive, sure. But you never have to buy it again – because it lasts. And a lot of people in this town get that. And there's the allure of getting something that you can't get anywhere else, that's made just for you in the way that you'd like it to be made. And it's made by somebody local, and you get to interact with them in the process of designing and building it: That has a lot of value. And for the past few years, my overhead has been super low. When the recession was getting going, I moved my shop to my house – and my overhead went down by almost 100 percent. So I had a little safety net. And I've been building a reputation for myself, getting a referral from a referral from a referral, the whole network thing. So that's how I'm doing it: Luck and timing and low overhead during the tricky times.

AC: Is there, after all these years, a specific kind of wood that you prefer to work with?

MY: Walnut. I work in a lot of different materials, but if I were building things for my house, it'd be walnut – because of the finished look of it, the color and tone. It's nice to work with, too: hard but not so hard that it's hard on your tools. It takes a plane well, takes a chisel well, smells great. It's very stable, and the grain is beautiful. And it's a North American hardwood, not imported from South America or wherever. It can be sustainably harvested.

AC: Is your grandmother's casket walnut?

MY: I think it'll be something a little more midrange in cost and lighter. Not quite a pine box but visually lighter than a big mahogany thing. And there's a certain price we're trying to hit, too, that'll be comfortable for her and allow me to make it for her. So we're keeping the material costs down.

AC: Not to be grisly, but is there a standard size or did you have to take her measurements like a tailor?

MY: I've made that joke to myself in my head, too, but there is a standard size. I didn't know this before, but there's a concrete second box that the casket goes into in most cemeteries. You know when you go to an old cemetery and there [are] graves that are kind of sunken? It's because the casket collapsed and all the airspace was filled up by the dirt falling down. So a lot of cemeteries require this concrete box, so no matter what happens to the casket, they don't have to fill in the collapsed hole. That's what defines the size of caskets: the plot size, then the concrete container, then the casket.

AC: Will there be hardware that you'll get from another guild member?

MY: No, it'll be built in, part of the wood structure. There's that pole, usually a brass pole, along the sides, and it's screwed in with some hardware. I'm going to have it integrated into the structure of the casket. The basic hinges I'll buy, but the rest of it I'll do myself. Because it's my grandmother, I'm going to put even more time into it, way more than I would for a normal project.

The Guild of Austin Artisans will exhibit work Saturday & Sunday, Oct. 8-9, 10am-6pm, at the Commodore Perry Estate, 710 E. 41st. A reception will be held Friday, Oct. 7, 7-10pm. For more information, call 922-4640 or visit www.austinartisan.org.