Constructing the Illusion of Depth

Four of Austin's master painters reveal the secrets of their craft

By Rachel Koper, Fri., Dec. 31, 2004

When a person decides to spend hundreds of hours painting, they want the end result to be complicated and not foolish. This article is about one geeky painter approaching four other Austin painters with a pepper spray of oddball technical questions about how they get that desired result. All four – John Cobb, Roi James, Will Klemm, and Mark Silva – work in realism: Cobb and James make portraits of recognizable people; Klemm paints landscapes with shimmering beauty; Silva portrays believable still-life contraptions, figures, and buildings. They work differently, but all clearly care about craftsmanship, naturalism, illusion, and beauty. All minimize the evidence of their own strokes, blending layers meticulously. And all share an obsessive-compulsive work ethic. You don't really have to ask these guys how they spend their time; the work hours ooze out of their paintings.

Their materials vary. Three of the four use commercial oil paints, drying agents such as Liquin, and a series of varnishes. John Cobb prefers egg tempera paint, a delicate water-based medium that's completely different materially from oil-based paint but shares a viscosity that makes it act somewhat like oil paint. Cobb mixes his own egg tempera paint and when he's finishing a piece, uses a blended wax to reduce gloss.

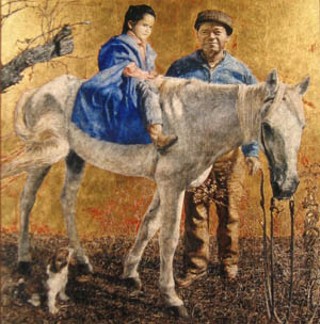

Since Cobb has worked feeding cattle, I ask him if he raises his own chickens for the egg in his egg tempera paint. "No," he laughs, but he does mix the paint fresh each time. Cobb likes the old ways of painting, the craftsmanship of building each part of the work. He uses an earth red chalk, graphite, and homemade carbon paper to make the underdrawing. None of the three drawing tools contain wax of any kind. This is important because the wax of a colored pencil or conté crayon would resist and deflect the absorption of the egg later. Cobb speaks of "getting really lost" looking at pieces of wood on an old barn door for the piece Madonna on the Farm. The wood itself was so complicated that he had to "get away from it, go into the studio to make sense of it." He takes his time, sometimes a whole year, putting details into the darkest shadows in a piece. The way Cobb draws includes every berry on every vine; his only way to work is full-on tight. It's a process that demands a lot of patience, but his mellow temperament seems well-suited to his medium of choice. He has to use the three different colors to simplify the layers of the composition, because his drawing never gets generalized. It's born complicated.

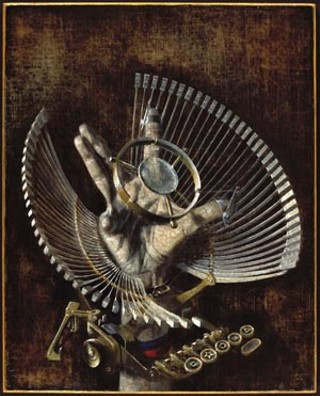

Similarities may be found in Silva, whose calculated strokes stay small and precise in even the earliest stages of creating an image. Silva insists on "making it look right," or he just doesn't want to look at it. "I underdraw with paint washes – Naples yellow if I'm feeling timid or burnt sienna," he says. "Sometimes I'll lay in some cerulean blue or something darker for contrast. Sometimes I'll go into a color wash or rough painted sketch and paint with turpentine, lifting out highlights or lines, making corrections."

Silva practically draws with the paint using small brushes. Typically each shape in the final composition exists in the early stages. "I tend to work thin; the work dries faster and allows me to go back in and rework things obsessively. I like erasing any evidence of earlier incarnations." So if he paints his hand as a saxophone, he will combine the live model with the still-life object both realistically portrayed. The trick is in the combinations, making the juxtaposition seem natural. Silva talks about doing "rate tracking" in his compositions. Once he's chosen a source of light, he pretends he's following a light beam as it bounces around a real environment. If he can't imagine a particular shadow or reflection, he has a lamp and clump of clay in his studio and will test it on the model, then use that in his painting. For a minute, I think about the programmed "physics" of video games. Silva wants to achieve an obvious realism, to trick the eye into believing the physicality of the new object environment in his painting. He wants it to look like a real thing – not paint strokes, but the texture of the real objects.

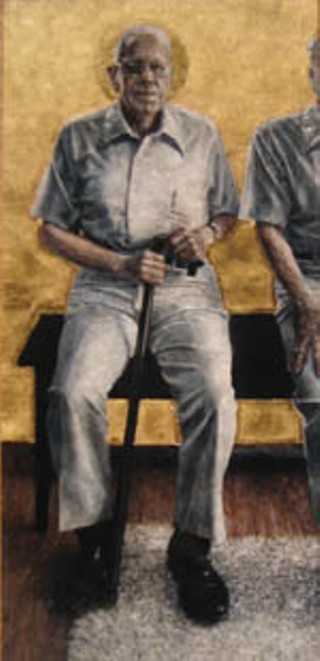

Roi James shares this lack of emphasis on the "hand of the artist." When he started painting figures, he copied Renaissance works from books he had. The images were printed so small that all evidence of the painter's strokes was invisible. James assumed that this utter smoothness was humanly achievable and started painting very soft edges. Over time James saw some of the actual pieces he had copied and realized they were rougher than he'd imagined.

His process is very controlled; he uses a projector for the initial blocking-in of forms. He uses more modern gadgets than the other artists. I ask him how much underdrawing he does before painting something.

"None on my figurative work. I hire a model and shoot about 150 images, four or five of which will be good enough to use. Then I work my compositions out in Photoshop, output them as slides and project them onto the canvas, and outline the important areas of the painting." This allows James to get straight into the painting, avoiding the perils of life drawing. He will often leave dark areas transparent with three or so layers. In contrast, the face will be opaque and have 15-20 layers of paint.

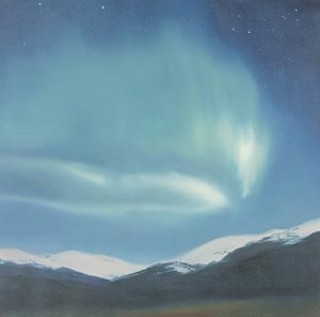

Will Klemm, best known for his pastel drawings, which he's made for 11 years, recently began oil painting again. "Variations in paint thickness and viscosity is the chief reason to use oil paint in the first place," he says. His sensitivity of palette and economy of form give the work a relaxing efficiency. He can imagine backlighting on anything and make you believe it really is sunset.

Austin Chronicle: What do you add to the oil paint? Are you particular about your brand of paint?

AC: Do you prefer lots of small strokes or several large ones?

James: Both. I use mostly sable or synthetic sable brushes. I prefer the softness to the bristles. The reason for this is my layers are so thin that a stiff brush will actually remove paint rather than set it down. The sables are much less likely to disturb the surface. When Im initially laying paint down I will use large brushes to create basic shapes of tone. Then Ill change to smaller brushes and define the shapes more clearly. Klemm: I use the biggest brush I can possible get away with, but Im not after some sort of signature stroke. I just like speed and efficiency. Cobb: The methods which separate and enlarge the traditional use of egg tempera include application of the paint using a palette knife; thin/thick; tiny and large brushwork; sealed resin coated surfaces to congeal and reduce fracturing; the reduction to previous layers using cheesecloth; and finally a great deal of small laborious cross-hatching in the traditional grisaille method. Silva: Small strokes are better. Losing significant brain function all at once scares me. For the record, though, Id prefer no strokes at all ... Is this a trick question?Most folks know that oil and water don't mix. Painters like these guys will really break it down for you. Cobb admits to having imported lead white from France. James even recommends his favorite brand of lead white. Why is the poisonous paint still around after all this time? It's just so darn smooth. The paint rolls off the brush. In addition to texture, painters look for mixing qualities. What does the pigment do in combination? How much pigment is in the oil? How finely ground is hard mineral pigment? These guys really know their materials and their craft. They spend their time constructing the illusion of depth; this is not a foolish endeavor. They have helped inspire me to slow down and get crafty this holiday season.

John Cobb has shown around the state but is not currently represented by an Austin gallery. Roi James and Marc Silva each have a Web site with their work on it: www.roijames.com and www.marcsilva.com. Will Klemm currently has a solo show running through Jan. 4 at Wally Workman Gallery, 1202 W. Sixth.