Ribbon on the Highway

The other side of Jimmy LaFave

By Dave Marsh, Fri., May 6, 2005

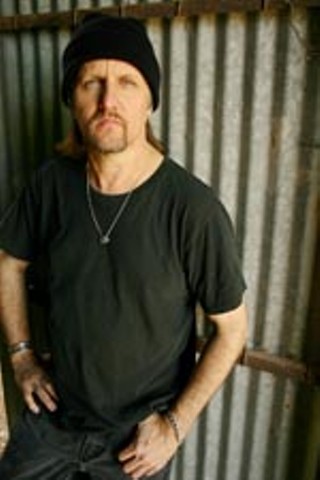

Here comes Jimmy LaFave. Maybe he's walking onstage to sing or slipping into the back of the Cactus Cafe to hear an old friend. Or lounging in a hotel lobby between gigs. Maybe he's walking up your driveway. The setting makes no difference. He's Jimmy LaFave wherever he goes.

He's about five ten, neither slender nor chunky. Wears a chambray work shirt over a T-shirt and jeans. A blue beret tops him. He doesn't wear it like a French intellectual. He wears it the way UN peacekeepers or Green Berets wear theirs. Either way, that cap's not gonna budge. It belongs to a man who knows how to keep it tight. On his face, a goatee and a slight grin. His sideburns are long, and a little dirty-blond hair peaks out from under the beret. A pendant bearing the image of a bison hangs around his neck.

You'd expect to find boots on his feet, but he's almost always wearing sneakers. Hard to say why. Maybe they're more casual. LaFave greets just about everything in life with immense casualness. Or maybe it's that he can't stand killing animals. He's been a vegetarian since childhood, not for health or religious reasons, but because he didn't like the idea of dead critters. Still doesn't. If he's wearing a leather belt, the untucked T-shirt hides it, befitting a guy who used to have a paunch. He's not much on guitar straps, either.

He looks like a truck driver, the kind of guy who might take on some impossible task: Get these oil rig parts from Stillwater to some place up in Montana you'll need a topographical map to ID, and do it by tomorrow night, no matter how often you have to leave the highway and go cross-country. He looks like the kind of guy who'd make it on time, too, Lynyrd Skynyrd or AC/DC blasting all the way, wisecracking cynically at the truck stops where he flirts with just enough intensity and manners to have all the waitresses primping when they see him walking in from the parking lot.

Jimmy LaFave used to have that job, driving for his father, who was a parts supplier, first based in Wills Point ("that's in Van Zandt County," the singer points out), then when he was a high school sophomore, in Stillwater, Okla., where his family relocated. LaFave's still got a long-hauler's instinct for wisecracks, though since getting married, the flirting's toned way down. He's still a dedicated driver; his agent, Val Denn, says he insists on driving to a lot of gigs even when it'd be cheaper and easier to fly. Friends in Oklahoma talk about scary runs on red dirt roads, flying through intersections in a pickup piloted with the legendary LaFave confidence. Driving is part of what defines him. He says he does a lot of his best writing out there, picking up images from road signs, for instance, because he once heard Bob Dylan did that.

Emotionally Yours

LaFave got to Austin exactly 20 years ago, when he was 30, during what he describes as "the golden age of singer-songwriters in Austin." He'd been visiting since a high school road trip got him to the Armadillo. It suits him to look like a don't-give-a-damn cheeseburger guy, and at least some of the time, it suits him to act like one. Here's the catch. There's this other Jimmy LaFave. That cynical exterior masks a remarkable degree of empathy and good taste.

This LaFave pops out of that carefully maintained dishevelment when called upon by the master of his fate, who is, to an amazing extent, Jimmy LaFave himself. When a friend needs a boost, LaFave turns on his warmth, not necessarily charm, just plain and powerful empathy. All his friends say something similar to Bob Childers, LaFave's songwriting mentor: "Jimmy's a really sensitive guy, but he spends a whole lot of time making sure nobody knows it."

"Singing is very emotional," allows LaFave. "You get obsessed with a lot of stuff. There's a sense of loneliness you have as an artist. That's why I close my eyes when I sing, because I like to go somewhere and find that place in everybody."

LaFave's notoriously generous with other performers, especially up-and-comers. He's had a hand in some significant careers – Abra Moore and Michael Fracasso come to mind – beginning locally by co-hosting open mics with Betty Elders at the long-departed Chicago House on Sixth Street, which uncovered a lot of talent, including Todd Snider.

For the past couple of years, he's led the Woody Guthrie roadshow (Ribbon of Highway, Endless Skyway), whose cast includes Childers in the role of narrator (inevitable given his quintessential Okie accent), locals Fracasso, Eliza Gilkyson, Slaid Cleaves, as well as Sarah Lee Guthrie and Johnny Irion, Joel Rafael, Ray Bonneville, and the Burns Sisters. Together with Nora Guthrie and Val Denn, LaFave put together the show, based entirely on songs and writings by Woody. He makes no star turn, ensuring the show isn't about anybody but its subject, an atmosphere that creates the sort of musical community Guthrie loved, onstage and off. LaFave is currently completing production on a Ribbon of Highway disc, a live set culled from 45 to 50 hours of recordings.

Empathy is why, even though LaFave pens most of the songs on his albums, he's best known as an interpreter of other people's material. That may be changing: His latest, Blue Nightfall, contains 11 originals, and they're by far the best he's written, particularly "River Road," "Shining On Through," and the extraordinary "Rain Falling Down." Nevertheless, he's one of the few contemporary singer-singers who work covers into their sets because they belong there – because he loves them and they're well-suited to his singular voice. He's got a gritty midrange, a thrilling ability to hit high notes, phrasing so adept that he can sing quasi-art songs like Jimmy Webb's "The Moon's a Harsh Mistress" as easily as "Oklahoma Hills" or "Have You Ever Loved a Woman." His is a pronounced vibrato, uncontrolled, but he can still shake a note 'til it almost breaks.

His forte is ballads; there's no other singer in Austin, or Americana, who can do as much with a ballad, whether written by him or someone else. His version of "On a Bus to St. Cloud" caused its writer, Gretchen Peters, to say that although she knew it was her best song, she hadn't understood it completely until she heard LaFave sing it. The version on his 2001 LP, Texoma, revels in phrasing so legato you can't tell if he really intends to come in behind the guitar. He luxuriates in the space created by the song's rhythms, even while recounting a tale bounded by madness and suicide. One of the things that makes his new songs so good is that he's given himself similar spaces to manipulate, as on "I Wish" and "River Road."

LaFave can get to the heart of ballads because he has such a magnificent sense of time. He commands the stillness between phrases even more than the lyrics themselves, which makes it seem as if every line is being uttered for the first time, after due consideration and from a place deep inside. His upbeat material has always been a little more problematic; he's best as a straight-up blues singer, doing something like "Key to the Highway," though he can rev up stomping Southwestern rock & roll. But truck drivers are loners, even or especially the most romantic ones. To turn that loneliness into art is a beautiful gift all by itself.

Maybe that's what makes him such a fine interpreter of Dylan songs, having recorded 18 (by my count) since his 1992 debut, Austin Skyline, including "Positively 4th Street," "Emotionally Yours," "Girl From the North Country," and "Buckets of Rain." He hasn't just run through them, either. No one, not a single singer, has ever sung Dylan with as much grace and insight as Jimmy LaFave. There was a haunting night at the Cactus Cafe a few years ago, when he dedicated a song to a close friend who had just suffered a genuinely tragic loss of a loved one. He sang "Emotionally Yours" as if it were his best friend who'd been killed, and he sang it not only without flaw but from deep, deep inside what the words mean. Sitting there in the dark, you could forgive yourself for thinking it was the first time anyone at all had sung those words to that melody.

Woody's Road

LaFave's been a champion of Woody Guthrie since he discovered the dust bowl prophet when his family moved to Stillwater, about 70 miles from Okemah, Guthrie's hometown. He's a scholar about the man.

"People don't understand what a genius he was," says LaFave simply.

He proudly plays a Guthrie guitar borrowed from the EMP museum in Seattle for the Ribbon of Highway shows.

"I want to let that guitar speak again. I think Woody would like that. It seems like he really loved his guitar," explains LaFave.

Now that's empathy. In his own shows, LaFave sings few Guthrie songs, other than a rousing "Oklahoma Hills." He also does Childers' "Woody's Road," the consummate tribute. LaFave identifies with Guthrie's enthusiasm, his determination, his fundamental optimism. He's not particularly interested in singing about mass social strife, and it's just as well. When empathy reaches out to the multitudes it can get pretty sappy.

The title Texoma sums up the Guthrie that got under LaFave's skin. The latter connects it to living in Oklahoma: "There's a vibe there that's not in Texas or anywhere else I've found." Lots of folks agree, and given its size, Oklahoma has an astounding track record of producing one-of-a-kind musicians – Guthrie, Charlie Parker, Bob Wills, Webb, J.J. Cale – but LaFave goes the limit. He notes that Oklahoma possesses "a frontier spirit, with an Australian edge to it" and that "you can hardly see a band in Austin without an Oklahoma musician." It's the desolation that makes Oklahoma beautiful, "like the Delta before you get to New Orleans." For LaFave, such statements form a kind of gospel. Rather than allegiance to ethnicity, religion, or class, Jimmy LaFave is a patriot of Oklahoma. If you mention Skynyrd, you're going to be reminded that Steve Gaines was from Oklahoma.

Onstage and on his albums, in his songwriting and song choices, LaFave eschews Guthrie-style politics in favor of intricate commentaries on romantic love, human connections, and the delights and sorrows of rambling. The closest he's come to writing about issues is a series of metaphoric songs about Indians, most plaintively on "It's Gone," from Blue Nightfall, most definitively with "Buffalo Return to the Plains," the title song of his 1995 album.

It isn't as simple as passion and obsession, influence and raw talent, either. LaFave wouldn't let it be. He has a mulish streak. For instance, he's the only one of the five kids in his family not to go to college, even though Stillwater's a college town. He was already playing bass in rock bands like Night Tribe. He explains this as the practical choice: "Once I discovered music, I didn't want anything to fall back on."

Then there's record producers – he hasn't worked with one since a semidisastrous, altogether unproductive pairing with Dylan associate Bob Johnston. "We did a lot of songs," he says, "but it was a bad experience."

He has a thing about record labels, too. He worked with Johnston when both of them had a deal with Tomato Records, home to Townes Van Zandt. He quit Tomato, and refused to consider other labels even though there was interest, vowing, "I'm never gonna sign with a label again," an attitude he describes as "jaded," though it's more like naive. Or maybe not; he didn't turn down a publishing deal with Polygram.

He came close to not having a record company with his first six albums, which were released on Colorado-based indie Bohemia Beat. In 1992, Mark Shumate, a fan LaFave says wanted to be a patron of the arts, "loaned me the money to do some live recordings at La Zona Rosa, and that led to Austin Skyline." Shumate created Bohemia Beat to release it, but showed little interest in being a label executive (one album came out without a copyright notice), let alone a promoter or marketer, though he did hustle up distribution through Rounder. Shumate did much better as a patron of the arts, releasing Abra Moore's solo debut and two albums by Michael Fracasso.

Denn, who's as close to a manager as LaFave has ever come, says his recalcitrance extended to an adamant refusal to so much as hire a publicist when he put out his double-disc live compilation Trail in 1999. "We had a real disagreement about it," she says. "I thought he was making a huge mistake, but in the end, the record outsold his others. Jimmy always acts like he knows exactly what he's doing. The thing is, he usually does."

It Takes a Train

Somehow, each of the Bohemia Beat albums sold 40,000-50,000 copies, numbers helped enormously by LaFave's popularity in Europe, particularly Holland. LaFave mentioned this in an interview, knowing most singer-songwriter albums are lucky to sell 10,000, but he wasn't bragging. The number simply slipped out.

Blue Nightfall, his first new album in four years, came out this spring on Red House, the Minnesota-based label whose roster counts veteran singer-songwriters Eliza Gilkyson, Greg Brown, John McCutcheon, and Guy Davis. It's his seventh album, but the first on anything that might be described as a real label. Still no producer, but he did let Red House owner Bob Feldman choose the track sequence. It's the best sequenced of his albums.

More than ever, this other LaFave can be heard in the songs on Blue Nightfall, all but one of which is an original. "Don't want to get out of this car, I just want to drive and drive," he sings in the opening lines of the title track, then goes for it all: "Into the fading light, and pretend I'm alive." With spare accompaniment by keyboardist Radoslav Lorkovic and a pulse rather than a beat, LaFave comes to territory mined by Bruce Springsteen and Patty Griffin and stands shoulder to shoulder with them, largely because, like them, he's as devoted to performance as to writing.

The gain can be attributed to that four-year layoff, or more precisely, to the events that resulted in it. They began while LaFave was still touring behind Texoma. Barb Fox was pregnant, and she and Jimmy decided to get married. (He'd had a brief first marriage back in Stillwater.) But the same squeamishness that made him a vegetarian made Jimmy jumpy about being present for the child's birth. So he was in Montreal when Fox bore their son, Jackson, on May 12, 2002.

Jackson clearly changed his father's life, and in every way, the change was positive. LaFave kept working, but he only went out for a week or two, occasionally three, not the long rambling stints he did before his son was born. He wanted to be home for those first few years. He wasn't in any hurry to make an album: "I did what I always do, make an album when I have 12 good songs and I'm ready." One more crucial thing happened: His mother was diagnosed with cancer.

When Bob Childers wrote "Elvis Loved His Momma," he tapped into one of the secret truths of rock & roll: They're all mama's boys, from Elvis to the Beatles to Bruce to ... well, Los Lonely Boys talk a lot about their dad, but I bet you anything if you cornered them in dead of night, it's mama who got 'em through the bad times. LaFave fits the mold, and he has more reason than most. His mother led gospel gatherings up until just before her death. She bought Jimmy his first guitar using green stamps. When she was entering the final phase of illness, he didn't waste any time.

"I got Jackson and put him in the car and we just drove straight through to Stillwater. I was just in time. I got to spend a day or two there, and I got to play her my version of 'Revival.' She loved it when I sang that song in my shows, and it was so important to play the record for her."

She passed away in her sleep a day or two later, but her absence can be felt in any number of songs on Blue Nightfall. The most notable is again "Rain Falling Down." If the first two-thirds of the song are about a parent filled with joy at first sight of his child, the last verse comes from the grownup child who's dreading the big hurt about to come. The unifier is heartbreak.

In uniting those two halves – the child and the man, let's say – Jimmy LaFave steps forward as a much more complete artist. He's always had talent and never lacked for vision, but his songs now reflect a sense of purpose that hasn't been there before. In fact, he thinks there may be "a renaissance of music going on," albeit mostly in coffeehouses and at house parties. He says that's fine with him. Jimmy LaFave never went out of his way for stardom. From the beginning, he's been concerned with self-expression and integrity. This goes to the heart of his self-confidence. He's always felt that being the best version of himself was plenty. So he says, with pleasure and not a hint of sarcasm, "I lead a pretty good life." A beat. "I don't sleep on people's couches anymore."

There will always be two Jimmy LaFaves. It's as natural as needing to laugh as well as cry. ![]()