Iraq Comes Home

Wounded warriors return to the Thin Blue Line

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Sept. 19, 2008

Investigating a report of an armed combat in a nearby neighborhood, two officers cautiously approached the scene. As they came in sight, one of the fighters broke and ran. In quick pursuit, the officers chased him to a footbridge and across a highway, as he ran toward a crowded marketplace. They yelled for the man to stop, but he ignored them, running faster, soon to disappear among the crowds of shoppers. Suddenly, one of the pursuing officers pulled his weapon and began firing. He fired three times in all, into the marketplace – until his partner finally yelled for him to stop and holster his weapon.

A few minutes later, they caught up with the fleeing suspect and subdued him.

Austin or Tikrit?

The Firefight

On March 14, 2007, a little after 8am, Austin Police Officer Wayne Williamson heard veteran Officer Lonnie Edwards on his radio, requesting backup. Edwards was responding to a call of two men fighting in the street on Purple Sage Drive, just off Ed Bluestein Boulevard. One man, possibly high on PCP and dressed in a black muscle shirt, his arms a canvas of tattoos, had left the scene and was allegedly armed with a knife. Williamson and another officer, Chris Davis, finished up the mental-health call they were attending to, got into their separate cars, and headed toward Purple Sage.

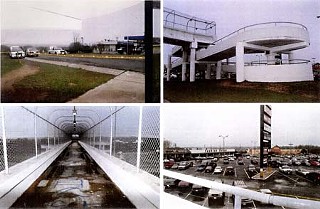

At 8:18am, Williamson and Davis pulled into the parking lot of the Chevron station at the corner of Purple Sage and Ed Bluestein, near an overhead pedestrian footbridge that spirals up three stories, crosses the road, and turns back down again, into the Springdale Shopping Center across the busy boulevard. Edwards, still on Purple Sage, came back on the radio, saying that the possibly armed suspect was now on the pedestrian bridge and headed toward the shopping center. Williamson and Davis drew their firearms and headed toward the bridge. Williamson scanned the bridge but didn't immediately see the suspect (later identified as LaCharles Williams); finally he spotted Williams, peeking over the side of the bridge ramp. "Austin Police! Stop, or I'll shoot!" the officers yelled, Williamson later told Internal Affairs investigators. He could see Williams from "about the shoulders up," briefly, before the suspect's head "drops back down." Williamson could not see Williams' hands or any weapon.

Weapons drawn, the two officers began moving up the ramp. "We make the first turn and look at the second level; there's nobody on that level. So we continue forward," Williamson told investigators. The officers continued up the spiral ramp to the top, where the bridge, enclosed by chain-link fencing, spans the road. "As we're approaching the last turn to get onto the bridge, I see the individual running west on the bridge," Williamson recalled. The officers again yelled for Williams to stop; he kept running. "So we get up on the bridge. As we get up on the bridge, Davis passes me. So the individual is about three-quarters of the way [across] the bridge. Davis is passing me, and I'm still running."

Reaching the far end of the bridge, Williams began his descent toward the shopping center parking lot. Davis was closing the distance, turning into the first downward spiral. Moving along the bridge but still behind Davis, Williamson stopped, aimed his weapon through the chain-link fencing toward the fleeing suspect, yelled once more – "Austin Police! Stop, or I'll shoot!" – and fired a single shot. Williams paused momentarily, Williamson said, but "after I squeezed off the round, he was running again." Davis continued to chase the suspect but could not catch Williams before he made it down from the bridge and ran west through the shopping center parking lot. Although it was still early on a Wednesday morning, the mall was already busy with shoppers going to or from the H-E-B or one of several doctors' offices, among them a pediatric clinic.

Trailing behind his partner, Williamson stopped when he made it to the first downward spiral. He saw the fugitive, still running through the parking lot. Williamson was worried: "In my mind, I've got a fleeing felon with a weapon," he explained to Internal Affairs. "He's going toward a populated area. If I let him get into this populated area, there's no telling what damage he's going to do to anybody who may be there, because if he's not stopping when we tell him to stop, what is he looking for? Is he looking for another way to get out?" Perhaps he was looking to steal a vehicle or take a hostage, Williamson worried as he looked over the side of the concrete ramp, down toward the parking lot where he could now see Williams racing toward parked cars, "and I fired the second round." Again, Williamson's shot did not strike its target – or anyone else. He "continued running," Williamson recalled. "I fired a third round. He continued running."

After Williamson fired the third time, he looked down to see his colleague, Davis, staring up at him, shaking his head. "I just stopped midaction and turned around and was screaming, 'No!' and [for Williamson] to holster his weapon," Davis later told department investigators. "I mean, that was a little extreme to be shooting at that particular point. It wasn't ... called for." Williamson reholstered and ran down the ramp to help catch Williams.

At 8:22am, four minutes after Williamson and Davis arrived on the scene, the two officers caught Williams and took him down. He was not armed.

The Aftermath

It was no more than a stroke of luck that Williamson did not kill anyone that morning. Each of the officers who eventually arrived on scene in the shopping center parking lot and were later interviewed by Internal Affairs expressed surprise over Williamson's decision to use deadly force in a situation that, each said, clearly did not call for it. At least one officer – Davis himself – was angry: Firing at Williams while Davis was in hot pursuit had put Davis in the line of fire. "It spun me for a loop," Davis said later. Academy instructors train officers how to avoid being shot by bad guys, "but you're not trained to be ... put in danger by your own guys," he said. "I mean ... the outcome of the events turned out okay, but they could have very well ... went the other direction."

Williamson's aggressive response that Wednesday morning was not only extreme – it was out of character. In the nearly 10 years that he'd been on the force, Williamson had not once fired his weapon. Indeed, aside from a scolding he'd received for using "inappropriate language," he'd never been in trouble before. His fellow officers considered him professional, and none of the officers interviewed by Internal Affairs detectives said they'd ever seen him lose his cool. Officer Edwards said he'd been impressed by how Williamson had remained in control on a call the two of them had once taken – the way Williamson was able to talk to the suspect, "like a father-son talk thing," was something Edwards said he would emulate.

The Soldier and the Officer

So what happened on that spring morning? Why did Williamson fire his weapon?

There is perhaps one explanation: He wasn't actually there. In body, there is no doubt Williamson was standing on the concrete footbridge in East Austin. In his mind, however, at the moment he chose to fire, Williamson might very well have been thousands of miles away, in the desert of Tikrit, Iraq, where he was stationed for nearly a year, starting in 2005. Indeed, according to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, "re-experiencing" a war zone is one of several classic signs of "combat stress reaction," which, if persistent and untreated, can result in post-traumatic stress disorder.

PTSD (and another little-understood cognitive condition, traumatic brain injury) has claimed thousands of military victims returning from the front lines of the "war on terror." And because this is the first foreign war in U.S. history fought largely by "civilian" forces – that is, the thousands of men and women with the National Guard and military Reserve – there are a lot of home-front consequences for soldiers as they try to reintegrate with their families and careers. Methodical, planned reintegration is of particular concern when it comes to those soldiers who at home work in law enforcement, says Dr. Audrey Honig, chief psychologist with the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department and chair of the Police Psychological Services section of the International Association of Chiefs of Police. "Absolutely, because with 'normal' people, you never have to have a gun in your hand again," she says. "With law enforcement, you do."

Williamson is one of at least 36 Austin police officers who have been called up for active military duty since 2001, deployed to the war zones in Iraq and Afghanistan, and he is one of thousands of civilian police officers nationwide who have been called to serve in the Middle East as part of Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom. Although seven years have passed since the U.S. first engaged in combat, only recently have police departments gotten serious about developing programs to help their officers make the transition from a life of military combat to a life of relatively peaceful policing. The transition is crucial yet has been as good as ignored by many police departments, says Honig – including, it seems, at least until very recently, by the Austin Police Department.

It is an oversight that can have deadly results.

'It Doesn't Just Shut Off'

Ultimately, APD Chief Art Acevedo terminated Officer Williamson for the poor decisions he made during the March encounter with LaCharles Williams. "This was a deadly force encounter that should have never occurred," Acevedo wrote in the Aug. 27, 2007, disciplinary memo that announced his decision. (Williamson appealed the decision but this month reached a confidential settlement, under which he is leaving the department and returning to his National Guard service.)

Immediately after the incident, in March of last year, Williamson had thought his decision to fire at the fleeing suspect was sound. Although he never saw Williams' hands, he'd been told the suspect was armed. If Williams had panicked in the shopping center parking lot and felt cornered, he could easily harm, or kill, an innocent bystander – Williamson felt compelled to act.

A year later, however, in hindsight, Williamson has become certain his decision to shoot was a bad one. In the interest of trying to prevent a fatal outcome, Williamson's actions nearly caused one. Only one of the three bullets Williamson fired into the parking lot was ever recovered: A single .40-caliber round was found lodged in the back seat of a blue minivan parked near the pediatrician's office. At the time the shot was fired, two children – a 14-year-old girl and her 4-month-old brother – were sitting inside the van. Fortunately, neither child was injured. Today, Williamson says that if faced with the same set of circumstances, he would not again choose to fire his weapon.

But it also seems that Williamson's decisions that day may have been prompted, at least subconsciously, by what he'd learned during his 11 months in Iraq. "Bad guys get away over there, they come back with things strapped to their chest, and they don't mind blowing themselves up – or you or somebody else around you," he said this summer. That was a soldier's lesson it seems that no one at APD thought to help him unlearn before he returned to patrol.

Williamson joined the Army right out of high school and stayed there for nearly 10 years before he left for civilian life in 1996. He joined the APD, which had sent a recruiting contingent to Fort Hood, a year later. He trained in the Central East Area Command and, save for a stint patrolling in the Southwest portion of the city, spent his career on the Eastside. "And then I got deployed," he said. Like a lot of former active-duty military officers, when Williamson's active term of service had expired, he decided to continue with the military as a member of the National Guard. "I could've walked away from the Army," he recalled recently, but because he'd invested a significant amount of time in the military, "you should probably get some return on your investment," he thought. "So, I'm like, OK, go to the National Guard, do the weekend warrior thing, and finish up."

In the wake of 9/11, things changed. Even though Williamson understood what the attacks in New York and Washington, D.C., might mean for the U.S. military, he was nonetheless surprised when, in August 2004, he got a letter in the mail saying that he would be sent to Iraq. A week later he was shipped out to meet up with the Guard unit he would serve with in the desert. By December, he was in Iraq.

When he returned home in July 2006, Williamson considered himself lucky. "My philosophy when I first got back was, 'I've got my fingers and my toes, and it's a good day,'" he said. Others he'd served with weren't as fortunate – one guy had gone out to brush his teeth and had his lower legs blown off when a mortar landed at his feet. Williamson had his own brush with disaster: The one day he missed lunch at the mess hall, six mortars landed in the parking lot, right near where he usually sat. From that day forward, Williamson ate alone in his room. Constant explosions were a given in Tikrit, Saddam Hussein's hometown – in fact, says Williamson, "people got nervous when something didn't blow up." He was an intelligence officer, and soldiers would come to him when it was too quiet, wondering if that meant Iraqis were staging for a large attack. Not knowing what would come next, it seems, was as stressful as a constant percussion of mortar strikes.

Understandably, Williamson was just happy to be headed home. On the way back to the States, he was given a government pamphlet that discussed strategies for reintegrating with his family and detailed the warning signs of PTSD and combat stress, but that was all, he said. Back in Austin, he quickly returned to APD. His road back to patrol started at the department's academy, he said, where he had to take a written test, required to maintain his peace officer's license. He requalified with his duty weapon and did some retraining to make sure he was up-to-date. That, he says, was all.

Back on the street, Williamson says, he felt fine – at least at first. In hindsight, he knows that things weren't the same. He was quick-tempered in encounters with the public and was easily irritated in traffic. Things weren't exactly the same at home either. At times he lost control, at least for a moment – the sound of water boiling in a tea kettle, sounding like missile fire, set him off, fleeing across the room. He doesn't remember the particulars of the incident, but his wife and mother-in-law do, he said. He was apparently sitting in the living room, watching TV, when the kettle sounded. His wife and mother-in-law were sitting in the next room, at the kitchen table, they later told him, when he bolted, running toward them. "I remember looking up, and my mother-in-law was looking at me, and she said, 'Are you OK, sweetie?'" he recalled recently. "I'm not sure exactly what I did. She said, 'It looked like you were looking for somewhere to go.' I'm like, 'Probably so,' because if you've got incoming fire, you don't run away; you run to the location it came from," because that's the only place you can be sure that it won't land. "So you listen for the whistle, and you run to where it came from. I ended up in the kitchen."

It wasn't until after the shooting incident in the parking lot, some nine months later, that Williamson actually realized something was wrong. By the time his case was in front of the Disciplinary Review Board in August 2007, before Acevedo and the rest of his chain of command, Williamson was ready to admit not only that he'd made a mistake but also that it was possible that the time he spent in Iraq had affected his decision-making. "That day, I posed a threat to other people ... innocent civilians," he told Acevedo. "So my job is to protect and serve. If I'm a greater danger to the people than the guy that I'm chasing, then there's ... something definitely wrong there, sir." Williamson was not then, nor is he now, sure how his military deployment played into what happened – or if, in that moment, he might have been transported, at least emotionally, back to the desert. "It's hard to say; it doesn't just shut off," he said. "So, I thought I was honest in saying [to Acevedo], 'I don't know if it affected [me] or not.' But it's like, do the math: The guy's been working with you for nine years; before he goes [to Iraq] he's never fired his weapon. He comes back from Iraq, and he fires his weapon," he posits. "What was the major component in that equation?"

Williamson's explanation did not satisfy Acevedo, who wondered repeatedly during the August Disciplinary Review Board why, if he'd been having problems, hadn't Williamson said anything to anyone before the March incident? It was a question Williamson could not answer. "Before you have a shooting ... your condition isn't to an extent to where you even have any treatment, don't go into counseling, don't do anything. You have a shooting, and then all of a sudden, you have this issue from Iraq," Acevedo said, according to a transcript of the board proceedings. "My thinking is that you've almost described a theory of the defense of your actions ... by talking about, 'Hey, I was in Iraq, and I have these [issues].' But other than you saying you were experiencing it, I don't see the evidence to support that you were experiencing it, if that makes any sense," he continued. "It's almost like, 'Hey ... I'm trying to use it to justify a bad shooting.' Do you understand what I'm trying to say?"

"I understand what you're saying, sir," Williamson replied.

Acevedo concluded that Williamson should be terminated. "Officer Williamson's actions occurred without excuse and/or justification and lead me to question his suitability for continued employment as a peace officer," he wrote on Aug. 27, 2007. "Moreover, he failed to provide sufficient information to mitigate his willful disregard for departmental policy, state law, and appropriate tactics and procedures."

'War Changes You'

Williamson's story is not unique. According to a recent study by the nonprofit RAND Corp., nearly 20% of U.S. service members deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan (about 300,000 individuals) now suffer from PTSD, an insidious form of combat stress reaction. Common symptoms of PTSD are "arousal" (agitation, irritability, or feeling "on guard"), avoidance, and, notably, "re-experiencing" (thinking about combat or feeling "as if one is still in combat"), according to the VA's National Center for PTSD. Yet only about 50% of those in distress actually seek treatment, reports RAND. Many avoid being diagnosed, fearing negative career consequences, and only about half of those who do seek treatment actually receive adequate care. "Safeguarding the mental health of these servicemembers and veterans is an important part of ensuring the future readiness of our military force," the study notes. Yet, fundamental "gaps remain in our understanding of the mental health and cognitive needs of U.S. servicemembers returning from Afghanistan and Iraq, the costs of mental health and cognitive conditions, and the care systems available to deliver treatment."

PTSD has been observed in all veteran populations – from World War II to Korea to Vietnam – after which 31% of male service members report having experienced PTSD, notes the VA. But this time around, says Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department psychologist Honig, the effects of war are felt far beyond traditional military populations. "This is the first time ever that we've seen civilians activated," she says. "They'd joined the Guard – yes, they should've known they could've been activated," but prior to 9/11 that was a "one in a million chance." As a result, more civilian police officers have been sent to war. Since 2001, she said, the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department has seen 300 employees deployed – some as many as four times.

It wasn't until very recently that police professionals began to consider that they might be facing a serious problem: Having officers on the street suffering, undiagnosed, from combat stress reaction or PTSD is serious and could be deadly. Reintegration, she said, "is critical" to avoiding disaster. "You don't want a police officer having a bad day" – having flashbacks, feeling angry or anxious. "We need them attending to what's going on in the environment, not what's going on in their own heads." As recently as 2006, says Honig, who has spent 22 years with the sheriff's department, there were "no transition programs" available for returning vets – including those returning to police work. "This, sadly, is one of these experiences that we're learning as we go along, which is not the best way to learn."

Connecticut State Police Sgt. Troy Anderson, a Desert Storm vet, has seen the same thing in his agency, which in seven years has had 70 officers deployed to war in the Middle East. "The bottom line is this: War changes you," he said. "We had officers go over there [and come back] concerned with what they saw ... and we really had nothing in place" to help them reintegrate. "This war has been going on for six or seven years, and we didn't even have a policy in place." Anderson was determined to change that: With the help of the state's commissioner of public safety, he was able to get his department's vets together to talk and, eventually, to help put together a policy that outlines specific steps that each returning officer must take before going back on the street. "What we did before was welcome them home [and] say, 'Here's your keys, your cruiser is out back, and you're on tomorrow night,'" he says. "That's not good practice, and that's not good policing."

At the Connecticut State Police, says Anderson, successful reintegration rests in easing officers back into the job slowly. Officers first come back to work light duty, in plain clothes. They then head to the academy, where they learn about changes in the law and department policy and requalify on the firing range with their duty weapons. "By the time they get near the end of the second week, they're in uniform and back in their cruiser, but they're riding with a senior officer or sergeant," he said. The reintegration process in particular focuses on "the rules of engagement," he says: "In a combat zone, they're completely different than what they are at a mall." The Connecticut State Police do not mandate psychological visits, but they do make certain officers know how to access those services. The department also utilizes a "peer support program," under which vets are connected to other vets, which is key to the healing process. "In police culture, there is this stigmatization" about reaching out and sharing feelings, he said. But his agency wants its officers to understand that it "takes a lot more courage to reach out than to bottle things up until they become too much to bear on your own." Since the Connecticut State Police program started on Oct. 1, he said, 330 employees have "reached out" for help.

LASD's Honig agrees that giving military vets enough time to reintegrate is key, but she also calls voluntary programs insufficient. "We need to monitor them more; we need to mentor them more; we need to provide them more peer support," she says. "And we're still learning" – in part, that police supervisors can't simply "trust their [officers'] judgment that, yes, I'm fine." In L.A., officers are required to see department psychologists for "multiple visits." Making that a mandate removes any potential for feeling stigmatized, she says. Cops are "used to doing what they're told," she says. So the LASD has "set up an s.o.p.: This is how it works; this is what everybody does. It really has to be a mandatory thing." This is important, in part, because real problems rarely surface right away. Instead, she said, research shows that symptoms of combat stress or PTSD might take four to six months to develop. "People initially compensate. They make excuses for their problems," like why they're not sleeping well or why they're irritable, she says. That's why it is crucial, she says, for police agencies to make psych services easy to access – and mandatory for all returning vets.

Taking Steps

Prior to March 2007, APD's Williamson said he didn't think much about his experiences in Iraq or whether his time there might bleed psychologically into his job as a cop. "I was happy to be back in my job and going on with my life," he said. It wasn't until after the shooting that he began to consider that his service might be affecting him at home and on the job. He was irritable while driving, sure, and he'd been more jumpy – his wife would later tell him he'd inexplicably jumped from bed one night, plastering himself against the wall, but he didn't even remember that. Still, he didn't think anything of these things until he finally began counseling, after the shooting, with former APD psychologist Rick Bradstreet. "It just didn't seem like it should be that bad, because there were a lot of other people over there that had a lot more to deal with than I did," he said. "On some level you say, 'I survived it, so I should be appreciative of [that] fact.'"

After meeting with Bradstreet, Williamson changed his tune. "It's like, OK, whether you think there is an issue or not, you need to go through some recovery steps. Period," he said. "You need to sit down with somebody ... to try to sort some of those feelings out, what those feelings actually mean, and how that may or may not affect how you make a decision. [These are] not really things that average people are ... equipped to deal with when they come back from that situation."

Williamson and his attorney, Tom Stribling, are adamant that APD failed to do anything to effectively reintegrate Williamson and thus nothing to prevent the 2007 shooting. Indeed, Stribling says that at the time Williamson returned (under acting Chief Cathy Ellison), there were no policies addressing reintegration, save for a mandate that returning officers ride out with another officer for a while after returning to patrol. In Williamson's case, even that small step was ignored. "Initially, when he returned to the department, there should've been more retraining and evaluation," says Stribling. "And, secondly, when the incident occurred ... it should've been [handled] more as a training issue ... with an understanding of what he'd been through instead of [strictly] a disciplinary issue."

While the Williamson incident appears to have been passed over without much thought by APD officials, the story did catch the eye of the Travis County Sheriff's Office, where 13 employees are currently deployed to active duty. The incident prompted Victim Services counselor Kelly Hibbs to act, initiating a military deployment support program that helps employees not only with reintegration but also with support for employees and the families prior to and during military deployment. TCSO provides peer support and serves as an access point for other services – including psychological counseling. Returning officers are encouraged to take time off to spend with their families before returning to work, and when they do return, they're put through at least two days of field training and are required to partner up with another officer before returning to work solo.

In a war zone, said Hibbs: "They're always on guard; they do everything with their weapon. They drive fast – and if there's a kid in the middle of the street, you don't stop; you run them over. When they come back, there are laws. It's just such a difficult transition," she said. "Guys come back, and we expect them to go back on the street. They've seen people killed; they've killed people. They've seen all this stuff, and [if] they're not taken care of," things can easily go sideways. "Cops are held to a higher standard, a different standard. But they're humans too – they've got lives and families, and they're affected by things as well," she says. "So how can they not be affected by going to war and coming home?"

Although APD has apparently done little in the past to reintegrate officers home from war, it appears now they're taking a cue from TCSO. According to Lt. Chris McIlvain with the department's newly created Risk Management Division, while the department has always had a program in place to reintegrate officers returning from an indefinite suspension or from a career change, it wasn't until recently that the department began to consider doing more for officers returning from war. In April, McIlvain was responsible for adding mandatory appointments with a staff psychologist to the department's military reintegration program. "We need to do a little more for these officers, because their circumstances upon returning to work are a little different," he said.

This was not required when Williamson returned from war – nor does it appear that the department at that point considered that military veterans might have specific reintegration needs. Now, however, in the wake of Williamson's dismissal, things are changing. And although APD is still further behind the curve than TCSO, it appears that the Police Department is catching up.

Currently, McIlvain said, the department is working on building a peer support program, akin to what Hibbs has developed at TCSO, where officers are matched up with other officer vets. The peer-to-peer support system is in its "true infancy" right now, McIlvain said. He's got the volunteers ready and training identified but is waiting on money. "With the budget the way it is, it is a matter of prioritizing," he said. But he's certain it's just a matter of time before the program is up and running. "The Fifth Floor, Chief Acevedo, is behind it," he said.

It may be too late to help Williamson, but his experience may at least mean that the department is now in a position to address future problems. In reality, says LASD's Honig, police departments across the country are playing a serious game of catch-up, evolving vet-specific programs to meet a growing need. (The International Association of Chiefs of Police will soon release a series of recommendations and a model policy designed to address the issue, she said.) "With the best of intentions, we've been negligent," she says. "It wasn't malicious, but it was negligent, by not preparing these officers for reintegration."

*Oops! The following correction ran in the September 26, 2008 issue: A printing error in last week's paper bungled the bylines of staff writer Jordan Smith, author of cover story "Iraq Comes Home," News, and contributor Doug Freeman, author of "Lunacy and Sorrow," Music, both Sept. 19. Food and Music section headings in that issue were garbled as well. The Chronicle is bummed about the errors.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.