Making Biscuit

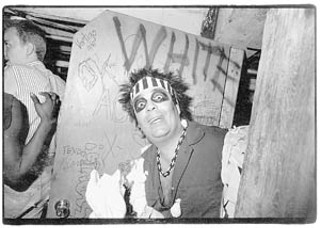

Punk icon Randy "Biscuit" Turner serves art 24/7

By Marc Savlov, Fri., Aug. 19, 2005

A modest frame house in South Austin sports a wealth of year-round yard art. Bowling balls ring the corner lot oak, a clutch of oversized scorpions guard the screened-in front porch, and the trees in the backyard rain oddities. Not one but two prominently displayed "No Solicitors" signs are affixed to the front door.

Austin's never lacked in curbside chaos; iron armadillos encroach on pink plastic flamingos, and coolly ironic lawn jockeys stand kitschy guard against the forces of dull suburban sprawl that breed and spawn elsewhere in the state of Texas like roaches in a midnight kitchen.

As for this particular South Austin home, the one with the surrealist landscaping, Bachman-Turner Overdrive said it best: "You ain't seen nothing yet." Inside, there's an entirely different reality. Walls are covered floor to ceiling with a laff-riot of psychedelic artworks, from garish paintings and improbable collages to dioramic displays featuring dissected baby dolls. It's not so much a house as a state of mind(warp). Welcome to the inner playscape of Randy "Biscuit" Turner, one-time frontman of storied Austin funk-punk-skate rock legends the Big Boys, as well as Cargo Cult, Swine King, and current member, with Houston's the Slurpees, of the Texas Biscuit Bombs.

Turner's musical legacy has spread far and wide since its Eighties heyday, drawing into its orbit punk peers and progeny such as X's Exene Cervenka, Fugazi's Ian MacKaye, and Jersey spookster Glenn Danzig. Yet the artist-in-residence known as Biscuit is at least another lifetime more than the sum of his musical resume. His art – like his music – is known and revered far outside the 78704 and 512.

It's that seemingly ceaseless stream of mad-funkateer artwork as much as those growly punk rock pipes that has ensured Turner's enduring notoriety amongst the underground's forever fickle cognoscenti. Those explosions of Bizarro World hi-jinks frosted in daubs of blinding, Tokyo-esque neons and chockablock with cheerful chaos have done as much to keep Ausin weird as anything else the city has ever birthed.

And the bearish Turner, exuding a wickedly youthful charm so utterly devoid of pretense or posturing, presides over it all with the bemused bafflement of a vaguely naughty schoolboy who's just been elected class president.

The Good Old Daze

If you're of a certain age and mind-set, if Austin's legendary Drag-bound punk club Raul's stirs beery reptile memories at the base of your brain, if fun, fun, fun is more than just a noun in triplicate, Turner needs no introduction. But for latecomers, and there are many, this is the Biscuit bio in brief: Born with a bang in post-war podunk burg Gladewater, Texas, circa '56, Turner "got art" at an early age.

"Growing up, my mother encouraged me a lot," he says. "She was born in 1921 when Betty Boop was popular and she could draw Betty Boop like nobody's business. When the kids were going crazy, all four of us, she'd say, 'Let's draw!'

"I remember my third-grade art teacher looked me right in the eye and told me I had promise as an artist. I guess even at that time I saw things a little different than everyone else. Then in sixth grade I had a wonderful art teacher who took me under her wing and encouraged the heck out of me. So, believe it or not, while growing up in a little, 4,000-person town I had some incredible encouragement by artistic adults who were trapped in that ugly little nightmare of a school system, but were very, very good at what they did."

Despite the enticing post-high school promise of a life in the slow lane, and following a stint at East Texas State University, Turner hightailed it to Austin, where he "immediately began to hang out with the beatniks, drink wine, and learn how to roll joints." For its part, the local music scene was shifting from psychedelic to cosmic, the Armadillo World Headquarters open and longhairs flocking to town for cheap weed and cheaper rents.

"I got a place over by the university for $45 a month," he recalls. "About a week after I moved here, they had a big music festival out where the old baseball park used to be by where the UT art building is now. I remember it was the Allman Brothers, It's a Beautiful Day, Pacific Gas & Electric – all for $3, with people rolling joints outside in full view. I just thought, 'God, I'm in heaven; this must be Mecca!' It was a wonderful time for me because suddenly I was surrounded by my kind of people, who reassured me that I wasn't nuts and who immediately gave me the encouragement to start being as weird as I wanted to be.

"Austin opened me up to the vastness of other people like myself, people I could really trust artistically and with my soul. People who would reassure me that I'm not crazy, that who I am is okay, and that the most important thing is to be happy. And I think moving to Austin showed me that right away.

"I had grown up in a horrid little backwater East Texas town and been earmarked almost from day one as resident weirdo. I remember I had to tuck my hair under my graduating hat in high school so that they'd let me graduate with the other students. I had a peacoat mod outfit and a little John Lennon hat I would wear that would freak people out. It was pretty weird, and that sort of leaves an impression on you. Even now I equate things like this: If it's not at Wal-Mart, it doesn't exist. And that's what I think all these small-town Texans think. If it's not at Wal-Mart, it's not real."

Turner's endearingly flaky nickname, by the way – alternately "Biscuit," "Mr. Biscuit," or just "Biskit" – stems from one fateful, early Austin-residence day that he donned a chef's hat to a friend's barbecue. "I'd dyed it yellow, just a big, floppy, hippy-looking hat, and one of my friends told me I looked like a biscuit. The name stuck."

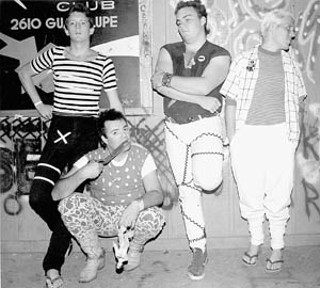

Fast forward a few years and suddenly there's another cultural bang: the Sex Pistols, the birth of the Austin punk scene, and campus-area freak nexus Raul's, now the Texas Showdown. It was an electric camaraderie of amps, vinyl trousers, and hair your mother wouldn't be caught dead in. Its reputation attracted name bands not just to the club but to Austin.

"I went to see the Ramones," remembers Turner, "and the Police at the Armadillo World Headquarters, the Runaways with Joan Jett, and a lot of early influential bands that were of that genre of music that was beginning to gel into punk rock and New Wave. You could really tell that something was going on, things were changing. There were people laughing and dancing, whereas previously, Austin had been pretty much all cosmic cowboy-style stuff, with everything painted in saguaro cactus green and not much else."

Turner's response to the DIY renaissance was to form the Big Boys with skateboard pals Tim Kerr and Chris Gates. He proved a natural frontman, sporting outlandish getups (a suit made of Baggie-wrapped sandwiches!) and possessed of a distinctively melodic and bluesy howl that recalls ex-Austinite Janis Joplin if she'd gargled volcanic sand as a whiskey chaser. Current Total Sound Group Direct Action Committee member Tim Kerr recalls Austin punk's early years as a time when creativity was as pervasive as the music itself.

"I'm not sure that there was necessarily that much more creativity at that point," reasons Kerr, "but it seemed like a lot of creative people got together at this one certain time, kind of like they did in the early Sixties with the beatniks. And that included music, art, writing, fanzines, anything – it was pretty much the kind of a scene where you were urged to participate instead of just sitting back and watching it go by."

Of the Big Boys' enduring popularity, Turner couldn't be more proud.

"I really think it was because we were totally off the wall," he posits. "We could have been generic and screamed and yelled like MDC or D.R.I., but instead we chose to do funk and stranger things. Tim's use of a radio on 'Sound on Sound' [from 1983's Lullabies Help the Brain Grow] is one of our most talked about songs to this day – people love that song – and he did that with a junky old international band radio."

A quick Turner/Big Boys gig poster aside:

"I did one poster for a Big Boys, Electros, and the Next show at Raul's that was so controversial the police came and shut the show down," notes the artist. "It had a picture of a nude male model with a big old hooter, posing in a cowboy hat with the words, 'Hot and Bothered Men Appearing Live at Raul's.' Well, we put them up all over the Drag and Congress only to get a call the next morning saying the APD had arrested Steve Hayden, the owner of Raul's, thinking that they were having live sex orgies at the club. The whole idea of punk rockers having orgies was just so absurd. I mean, look at 'em, they're like white, pasty little oysters. But the APD didn't get the joke."

Like Les Amis, Inner Sanctum, Liberty Lunch, and the Varsity Theater, the Big Boys and Austin Punk v 1.0 is long gone. "That really cool thing you missed," is recalled fondly, more often than not, by those present at its noisy, raucous birth and raised to iconic status by those who weren't even born yet. Tempus fugit, things change, and after a glorious six-year run, 1980-1985, the Big Boys packed it in after one final, infamous night of sheer chaos, both onstage and off, at Liberty Lunch. Acrimony ensues, but this is not that tale.

Gaud in Heaven

Turner, exhaustively creative, forged on with both music and art. He formed the short-lived band Cargo Cult before hitting his musical stride with the punk-performance-artstravaganza Swine King in the Nineties, an eight-plus-member outfit recalled as much for their outrageous stage props, costumes, and theatrics as their gorgeously chaotic musical output.

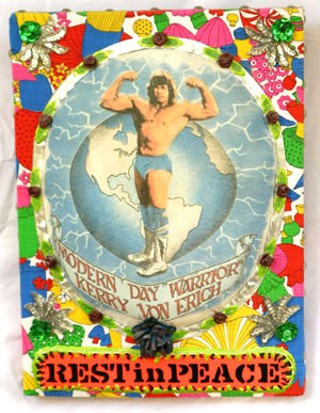

Throughout it all, Turner's artwork developed from a hodgepodge of found objects and cut-and-paste imagery into something else entirely, a world unto itself, made up of toy-box discards, swirls of acrylic and neon-gaudy temperas, dust storms of glitter, shattered mirror balls, and glue-gun assemblages served poppin' fresh from the Biscuit's inexhaustible inner oven. Man, art, and artist had become inseparable, and you couldn't help but stare and stare and stare.

Describing Turner's staggeringly original artworks without wearing out Rodale's Synonym Finder can be a tough job for anyone, even close friends who've had years to bask in the Biscuit E-Z Bake art-kiln.

"I'd call it carnivalesque," says X/Knitters founder Exene Cervenka. "It's ironic and it's funny. He's also one of the kindest people I've ever known. He's such a good person. And his house is the best art gallery in town."

Jim "Prince" Hughes, owner of Austin's original Japanese toy store-cum-punk rock outfitters Atomic City and longtime running buddy of Turner concurs:

"He's got a unique vision, and you can see it in his art. It's not like he went somewhere and saw an example of someone else's crazy art and said, 'Oh, I can do that, too!' His stuff comes from somewhere I can't even begin to guess at. I don't know that you can even describe it. It's ... construction with things pieced together and with a psychedelic bent to it, but really, more than anything, it's just him. Like Salvador Dalí or someone, you can't really put a finger on it; it's just what comes from inside him and goes out into his art and pretty much everything he does. He's like living art and always has been."

Another of Turner's old-school comrades Gary Floyd, of the Dicks, tackles the Biscuit mystique by simply calling it overwhelming.

"When you stand in his house and you're in the middle of all of it, you simply can't concentrate on one single piece because your eye will catch something else immediately. It's brilliant."

There are precedents, and not the dreaded "outsider art" tag, either. Sitting in his living room on an early weekday evening, Turner, shaggy-haired, slimmer than he used to be but still very much the husky-voiced, East Texas self-made misfit, rattles off a list of influences that range from the more-or-less expected, including Robert Williams ("because of his ability to paint chrome and his hot-rod fetish, something I share") and local poster artisans Guy Juke, Kerry Awn, Steve Marsh, and fabulous furry freak Gilbert Shelton, to the less so:

"I enjoy Mark Ryden's stuff a lot for the softness and the surrealness of what he paints," ventures Turner thoughtfully. "As for older artists who've been around for years, there's Alexander Calder, the mobile maker – I'm fascinated by things that hang in the air, especially ones that are so ordered. And his sculptures were huge, some of them 60-feet wide. They purchased one for the main lobby at Love Field before DFW was there, and I remember driving up just to go see that sculpture. Of course Salvador Dalí, I've always admired his entire approach, the minutiae, the detail, and the mind-boggling aspect of his work. Who else? The sculptor Henry Moore, Giacometti, Constantin Brancusi, Peter Max, and Frank Lloyd Wright."

Frank Lloyd Wright?

"Oh sure! C'mon, if his architecture isn't art, then what is?"

So how would you describe your artwork?

"I like to say it's as if Salvador Dalí met Diego Rivera and they went to lunch with peasant people who made dioramas in cigar boxes. I want to think of my art as little scenes of the absurd. Not so much in traditional diorama form, but completely mind-altered by my usage of combinations of ingredients. I love to juxtapose things, like taking the head off a Barbie doll and replacing it with a giraffe head and then placing her in an operating-room scene where she's the doctor and it's all in a 10-inch-by-10-inch space."

How about in one sentence or less, gun to your head?

"If clowns had art shows, then Biscuit would have the biggest red nose."

Cue gag-gun firing "Bang!" flag.

Mad Methods and Simple Junk

Every grandly eccentric artist ought to have a patron-cum-gallery-owner in their corner, and Turner has found his in Gallery Lombardi's redoubtable Rachel Koper, who's included Turner's work in several multi-artist exhibits, this despite the fact that when he first turned up at the gallery, she had no idea of his connection to Austin's punk rock salad days.

"When I met him I didn't realize he was a musician, at all," admits Koper. "He just sort of walked into Gallery Lombardi and said, 'Hi, I'm Randy, I'm an artist, and I've got some stuff in my truck right now. Would you like to look at it?' I did, and I was immediately impressed by the density in his work, the amount of detail, the time that went into it, the craftsmanship.

"Biscuit's work is busy. Sometimes it's glittery, sometimes it's pink and blue and green and yellow. So it has certain psychedelic elements to it, but it's also real childlike and fresh and emotionally honest. There's just something silly about it. And it's his personality that comes through – that tells you that this is a really sincere interpretation of what he sees through his eyes. When he looks at stuff he just thinks, 'How can people not think that's great?' Sometimes in America you just walk through strip malls and frown the whole time. Biscuit goes to Goodwill and thinks, 'Ohmigosh! This stuff is great!' He looks at the overlooked, and then says, 'How can I take this and make something new?'"

Creating new art out of found objects is as old as art itself, or at least as old as your local Goodwill, but Turner's mad methods are unique and affecting in ways that aren't seldom encountered outside of uneasy 3am dream-scapes.

His fluid, sometimes ominous artistic confabulations comprising what most people would take for junk, too raggedy even for the rummage sale – flambéed toy soldiers, deconstructed doll parts, intimations of Kennedy-era prosperity side by side with images of the malformed, misplaced, or misunderstood – are the giddily overt expressions of that inner Biscuit, the one who, when he spies an evil clown under his bed, doesn't turn tail and run the other way. Instead, he invites the Bozo up topside to help scour his treasure trove of neat stuff, dreaming up new and better ways to view a reality that, let's face it, isn't living up to its childhood promise very well these days.

"It's my world," states Turner, "and sometimes I retreat to it knowing full well that beyond that front door right there is horror and destruction and death and mayhem. But I know I can't control any of that, and so this little world that I've created here, well, I can barely control that, too, but it's much more fun.

"I'm very saddened by the pain in the world and overjoyed at the mundane. That sly grin that people have. I can cry in a moment for people's joy, and I hope that reflects in my art – every facet of life's existence, the sad, the gothic, the funny-as-heck things that I do. A lot of it is planned out, but often it's free-form, mainly because I've got 20-odd double-stacked boxes which are labeled on the side 'Toy Chaff.'

"And I'll pour a box out on my bed and look at all the little plastic legs, arms, dice, chickens, shrubbery, airplanes, and then suddenly I'll have six airplanes battling a Barbie who's got a Mexican wrestler's head out in front of a picture of a Baptist church that I cut out for the background.

"I love juxtaposing all that together because it's not real. It's a world I created that people seem to think is really funny. And I'm honored completely that anyone would laugh to start out with, much less at my artwork. Because that's what I've always tried to do: give people something to laugh about and also give 'em that tilt of the dog's head, that little 'Huh?'" ![]()

Mental Volcano will be on display Friday, Aug. 19, 6-10pm and Saturday, Aug. 20, 2-7pm at Pedazo Chunk, 2009 S. First. 441-3505.