The 12th of Never

The dispute over one Eastside housing proposal reflects a larger Austin conflict

By Wells Dunbar, Fri., Dec. 17, 2010

East 11th Street has changed.

Along with the welcoming arch and mosaic mural greeting entrants coming off I-35, there are indicators that it has evolved in smaller ways as well. The Longbranch Inn, which first opened in 1934, is now a popular haunt for local hipsters. Where Planned Parenthood offices once stood – at the "five points" intersection of 11th, Navasota, and Rosewood – there is now a wine shop. Across the street on Rosewood is a holistic health store offering yoga and acupuncture; behind it, Roller Derby girls serve sno-cones out of a trailer.

All that growth – and accompanying gentrification – has required investment: buried utility lines, street and sidewalk repairs, and capital improvement projects like the towering Street-Jones building.

East 12th Street hasn't changed as much.

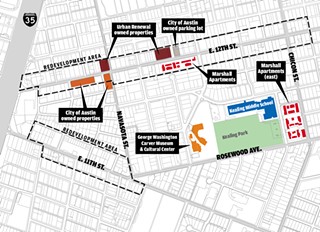

There are different theories to explain the apparent contradiction. The 11th Street improvements have primarily applied to commercial properties; 12th Street is more residential. The city has direct stakes in several portions of 11th, making it easier for redevelopment to take place; the city owns just four tracts and a parking lot along 12th, and quite a few of the undeveloped and underdeveloped plots along the street belong to several different owners. You can factor all that in, along with our protracted recession, which is seeing to it that less dirt's getting moved all over town.

But at long last, the city has something planned for 12th. Nevertheless, two nearby neighborhood associations are livid that a supportive housing proposal – including currently homeless people as potential candidates for living there – is the first major 12th Street proposal to come down the corridor in years.

Moving Targets

The Marshall Apartments account for 100 units of Section 8 apartment housing situated on two different properties: 1401 E. 12th – within the city's Urban Renewal zone – and 1157 Salina, about a block farther east, directly across the street from Kealing Middle School. Tenant turnover is low at this large, affordable complex in the Central-East area, with maybe five vacancies each year. Under the terms of a proposal initiated by City Council Dec. 9, $2.5 million of an affordable housing bond approved by voters in 2006 would go to rehabbing the property, with the stipulation that 20 of the 100 units, managed by Summit Housing Partners and local social-service org Caritas of Austin, would be set aside for permanent supportive housing – designed with social services to get formerly homeless people off the streets (see "What Is PSH?").

It's this PSH component that has some Eastside neighbors and property owners nervous. Their objections invariably return to Marshall's proximity to 12th and Chicon – "a long-time haven for open and obvious drug sales, vagrancy, and prostitution," as described in a Robertson Hill neighborhood memo opposing the project – and conversely, its proximity to schools. Despite Caritas' assurances about the project – that residents could be ejected for not following the program guidelines, that openings would be paired with fitting participants (for example, a vacant three- or four-bedroom unit would go to a family in the PSH program), and more – the proposal has garnered a decidedly mixed reception, ranging from lukewarm to downright hostile, with the Robertson Hill and Swede Hill neighborhood associations having voted against it.

The PSH complaints are, in some respects, nothing new; as in recent years, complaints have batted similar proposals around all over the city, including Mobile Loaves & Fishes' proposed supportive RV park for the homeless, last seen riling communities on the Eastside, in North Austin, and near the airport. But objections to the Marshall proposal are amplified by the fact that the project falls within the Urban Renewal area directing development along 11th and 12th streets – and neighbors' complaints that while 11th has blossomed, the first major investment on 12th in years is this admittedly controversial project.

Robertson Hill Neighborhood Association President Stan Strickland and Swede Hill Neighborhood Association President Tracy Witte had hoped to challenge the proposal at a special-called meeting of the Urban Renewal Board. They were rebuffed, and as the former agreement overseeing the area has lapsed, the board's inaction on the project additionally called into question its future role – if not the future of East 12th Street's place in the Urban Renewal Plan in general.

Who's in Charge?

The Marshall blow-up comes at a particularly trying time for the Urban Renewal Board, in the middle of a six-month term of a memorandum of understanding with the city concerning its role, as its members feel out their new place in the shifting Eastside power dynamic. The city's Urban Renewal Plan was developed to address serious crime and other forms of blight affecting the area. The guiding document of revitalization efforts, the plan directs land use in the revitalization zone along the 11th and 12th street corridors. As the document used to delineate the area and the city's authority, it overrides neighborhood plans and even zoning – and moreover, any amendment to the plan would create a protracted public process, with ultimate approval up to City Council.

Under the plan, three groups sought to direct growth in the region. The city acted as a property holder and financier; the appointed Urban Renewal Board weighed in on projects and policy, offering amendments to the plan as necessary; and the Austin Revitalization Authority broke ground and found tenants. This arrangement lasted until October, when the city dissolved its relationship with the ARA, following longstanding complaints about its bureaucratic inertia. ("[L]iquidity challenges, reliance on the City for income, and inconsistent financial planning all impact ARA's long-term viability," reads an introduction to a 2009 city audit of the agency.)

Regarding the Marshall project, opponents thought they could make their case to the Urban Renewal Board and potentially exclude PSH use through an amendment to the plan. The section of the plan regarding Marshall had been updated before, as recently as 2005, preserving multifamily zoning but requesting homeownership opportunities (condominiums) and doing away with a call to preserve the existing housing.

But this time, the requested change didn't happen. At a special-called November meeting, the board essentially said it was powerless to stop the proposal. Moreover, Chair Ben Sifuentes said (as quoted by In Fact Daily): "This is not within the purview of the Urban Renewal Agency. ... We can't vote against this project. It's against the law." Sifuentes then called on zoning officer Jerry Rusthoven and board legal council Charles Zech to further explain. Despite city involvement in the Marshall proposal, the sale is still a legal transaction between two private entities: the owner of the Marshall Apartments and for-profit developer Summit. With the buildings currently zoned multifamily and that zoning not planned to change (PSH is a concept, not any sort of zoning designation), there's nothing to prevent the proposal from going forward.

But if the board can't address a neighborhood issue as significant as Marshall, then what is its role going forward?

Urban Fireworks

That question was further clouded when, soon after the decision, Urban Renewal Board Member Sean Garretson resigned his post. In a memo addressed to City Council, he wrote, "Monumental and critical transition still lies before us; I would like to be a part of the progress we all hope will be achieved, but I no longer believe I can do so as a commissioner of a broken agency."

The Marshall decision was behind his announcement. "Noble as this endeavor may be, the public financing required to realize this project will be the first major City investment in 12th Street, and the project is being pushed in spite of broad and intense opposition from adjacent neighborhoods and East 12th Street property owners."

Garretson then went on to lambast the proposal's process – or lack thereof: "It was puzzling and disheartening that URB learned about the Marshall project at the 11th hour from concerned neighborhoods rather than via a timely and complete briefing from [Neighborhood Housing and Community Development]." He also blamed the chairman, writing, "Sifuentes dominated the proceedings by unilaterally re-ordering agenda items and allowing Summit and Caritas free reign to present the project's merits and dialogue with commissioners for over 90 minutes," and "berated the stakeholders present as gentrifiers who wanted 'everything pretty' and declared in advance that URB was powerless to act in this matter."

He concluded by calling for Sifuentes' resignation, writing that the "Chairman has served for too long, and his tactics have marginalized other members of the Board. The community and URB commissioners need an active leader whose abilities are equal to the task of leading the revitalization effort forward, but who is also able to ensure active input from all board members and the community."

Sifuentes was first appointed to the Urban Renewal Board in 1996, a staggering 14 years ago, and the 83-year-old lifelong East Austinite's tenure has been a source of often-heated discussion among Eastside stakeholders. Sifuentes declined to address any questions regarding the board's role or the Marshall decision on the record when called by the Chronicle, directing any questions on Marshall to the URB's legal counsel.

But while Garretson's letter called for fresh blood at the board level, it also decried a separate intrusion: "Though the City dissolved the Tri-party Agreement on October 1, it has yet to task a successor with ARA's former responsibility as urban renewal gatekeeper, and NHCD has unofficially positioned itself to fill that power vacuum, advocating the merits and compliance of proposed projects to URB commissioners. We find ourselves in the very situation that the original framers of the [Urban Renewal Plan] and the Tri-Party Agreement sought to avoid: a City department asserting its goals over those of the Redevelopment Project, to the latter's detriment."

The More Things Change

"I appreciate you asking about whether the city of Austin has asserted itself in this, whether we're filling a power vacuum," says Rebecca Giello, activity director of Neighborhood Housing and Community Development. "We're definitely, as the city, going to do everything we can to educate people about the importance of affordable housing, permanent supportive housing, and housing all along the continuum. But in this particular circumstance" – the Marshall affair – "we were providing information as it was being brought forward to the Urban Renewal Agency."

Giello and Gina Copic, real estate development manager for AHFC and NHCD, argue that the neighbors' hope to amend or zone the project out of order was never likely to succeed. "This is an existing development that is legal; it conforms with the zoning code, with the Urban Renewal Plan," says Copic. "They can rehab it without notification to the neighborhood. They're not changing the use. So there was no reason for it to go to the Urban Renewal Board, because there was nothing for them to act on." Giello also noted: "You really have to tread a very mindful path when you begin to try and dictate who can and cannot live somewhere with services. You can really get into fair housing issues."

So why did it appear on the board agenda in the first place? "We didn't bring this before them; the neighborhood did," says Copic. "I think the board knew there was nothing for them to act on."

While it's true the project may not be the type of mixed-use development seen along 11th Street, Copic responds that "the city and the Urban Renewal Agency do not own very much property along 12th street. It's very limited. ... There are multiple owners along that stretch, and there are not a lot of large tracts – there are more small tracts next to one another. In order to see a larger development, you'd need to aggregate multiple lots with multiple owners. ... There's just not a lot of opportunity for the city to, for instance, put out a request for proposals for the properties.

"Part of it is the economy, of course," she continues. "We recently put out an RFP for Block 16," the vacant lot just west of the Street-Jones building on 11th, "but the board made the decision not to accept the one lone proposal. Financing right now is difficult, but there've also been issues raised regarding infrastructure."

She says those infrastructure needs should be outlined in an upcoming market study of 12th Street, "hopefully to develop some implementation strategies that may help with future development, private development, and then also looking at our properties to see what the highest, best use of those properties is."

The question remains: Does Neighborhood Housing and Community Development's goal conflict with the broader aims of urban renewal along 12th? "We wear two hats," Copic says of her real estate work in the renewal zone. "One is housing staff, and one is Urban Renewal Agency staff."

"I think it's really important when you see the city of Austin has asserted itself to 'advocate,'" says Giello. "The desire to hear [the Marshall case] came at the board level. That does not mean that the city doesn't have an incredibly important role in making recommendations about housing projects based on the merit of the proposal. And the proposal that Summit has moved forward has merit to warrant a recommendation, period. Whether it's in East Austin, West Austin, Southwest, or Northeast, it's a good proposal. It just happens to be in an area that has created a great deal of conversation."

And as for the objections? "We're not putting anything different there," she says. "It's already there!"

Tangible Improvement

Giello sees one silver lining in the Marshall controversy: the opportunity to raise awareness around supportive housing. "We have a great task in front of us regarding education on PSH. And this has served as a great example. You certainly don't cherish situations like this, but you do look at it as an opportunity, when PSH issues elevate, to do the best you can to educate people about it."

More outreach could have helped at the Carver Branch Library in East Austin earlier this month, when Kealing Neighborhood Association members gathered to discuss and decide whether to support the Marshall projects. Questions regarding the terms of the PSH lease agreements were ample: For example, what would it take to remove a resident who wasn't abiding by the program? How would the prospective tenants be selected? Theories were floated: one, that the proposal was simply Downtown pushing its homeless problems East; another that the apartment rehab was simply a precursor to flipping the entire apartment complex for University of Texas student housing. However, the association narrowly voted to support the project. "There are no perfect solutions, but we feel that this is an opportunity for our neighborhood to be involved with a tangible bottom-up improvement," reads the association's letter to council in support. "We hope that it will encourage the city, developers, and property owners in our neighborhood to consider what they can do to improve conditions today, rather than continue to let opportunities pass by. We want to emphasize that we consider this project merely a beginning to an ongoing, collaborative process to improve the quality of life of our East Austin neighborhood, not an end in itself."

In council chambers Dec. 9, there was plenty of support for and opposition to the Marshall proposal (and not nearly as much attention paid to two other proposals on the agenda: PSH and low-income housing initiatives in both South and Southwest Austin, near Circle C – they quietly passed). Opponents dwelt on the "crack, alcohol, prostitution, and violence" of 12th and Chicon (and were in turn mocked by supporters for their war-zone descriptions), but the 11th/12th divide also loomed in the background. In contrast to PSH at Marshall, "Do you want to know what would be a great investment on 12th Street?" asked resident Rob Seidenberg. "Here's just the top of a small list: adding urban rail, burying power lines, improving bus stops, assisting small businesses, incentivizing the relocation of a large company onto the corridor."

Blackshear/Prospect Hill Neighborhood Association President Rudy Williams voiced his personal support of the project: "We do not want to turn it into mixed use with high-end housing. We want to make sure that poor people have a place to stay." But he also raised a concern unaddressed in the pleas for general redevelopment: "And as far as 12th Street goes, if 12th Street looked like 11th Street does now, there would be no minorities on 12th Street. ... 11th Street has been almost totally gentrified. Small businesses for minorities are basically nonexistent."

Despite passage of the initial $2.5 million in funding, this is not the last we'll hear of Marshall. City Council's Austin Housing Finance Corporation is set to schedule a Jan. 13 public hearing on issuing $6 million more for the Marshall rehab, and beyond that there's the council goal of putting 350 PSH units online in the next four years – out of an overall estimated need of 1,889. And with lurching local development putting larger projects on hold, local agencies like AHFC are the only ones spending cash.

Couple that with an Urban Renewal Board uncertain of its role post-tri-party, and it looks like the argument over properties like Marshall – if not the changing face of the Eastside as a whole – are just getting started.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.