25 Years Ago, Sublime Arrived in Austin and Cut One of the Decade's Biggest Albums

Local producer Paul Leary put some Austin in the Long Beach surf/punk/dub trio's mix

By Kevin Curtin, Fri., May 7, 2021

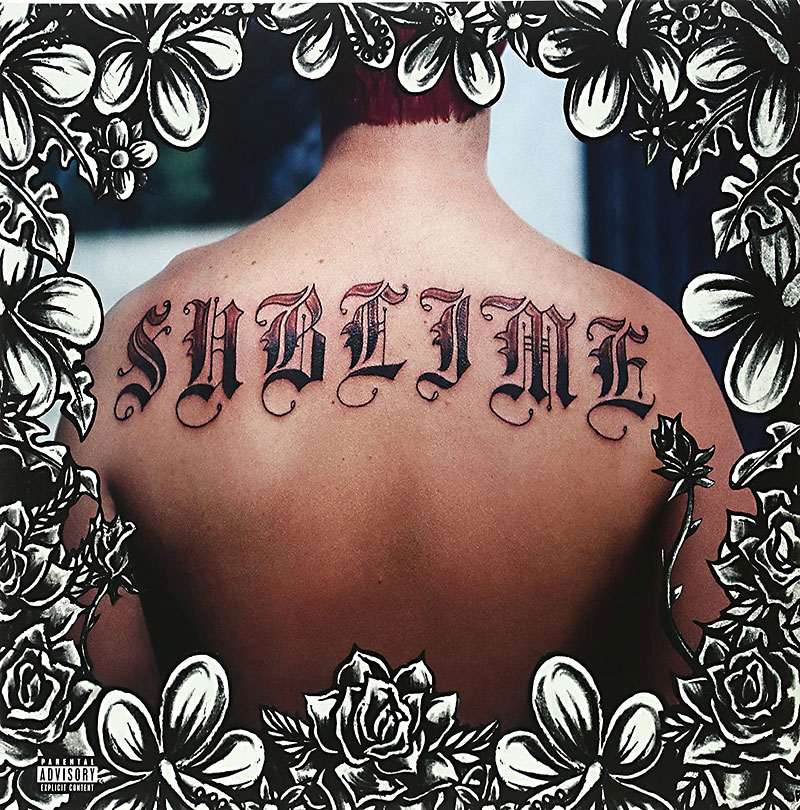

Epitome of tragedy and triumph, Sublime's eponymous third album became a generational touchstone only after the ashes of the band's lead singer, Bradley Nowell, spread out over the California shore. Ubiquitous CD in every teenager's car console in the late Nineties, the Long Beach trio's magnum opus spawned four radio singles: "What I Got," "Santeria," "Wrong Way," and "Doin' Time." A hybrid of reggae, dub, punk rock, and hip-hop released in July 1996, two months after the frontman's death, it sold 5 million copies by the end of the century.

The bulk of the landmark album's recording and mixing took place locally, at Willie Nelson's Pedernales Studio in Spicewood and Arlyn Studios here in Austin, between Feb.-April 1996. As Sublime's right-hand man Michael "Miguel" Happoldt puts it, "The spirit of Austin is all over the record."

Get Ready

"We were Butthole Surfers fans," Sublime bassist Eric Wilson recalls. "So when we finally had the opportunity to get a producer, we decided on Paul Leary."

San Antonio-hatched hallucinatory punk insurgents and Austin touchstone, the Surfers spawned their own universe of influence, including spinning off guitarist Paul Leary into a cottage production industry. The guitarist landed on the SoCal trio's radar after producing Too High to Die for the Meat Puppets, a group the Left Coasters adored. Nowell's closest friend who co-produced, played on, and put out the band's first two albums, Happoldt says Too High to Die reflected their aspiration: "Make a record that presented the most polished version of our true selves."

Leary first heard Sublime while recording with the Meat Puppets in Tempe, Ariz.

"I had a rental car and was listening to their local punk rock AM radio station and they were playing 'Date Rape' probably 100 times a day, and I just loved it," recalls Leary. "When I got the call from my agent, asking if I wanted to produce Sublime's record, it freaked me out."

The still-underground trio had signed to Gasoline Alley, whose parent company, MCA Records, underwent a regime change in late 1995. Jon Phillips, the A&R executive who signed and managed Sublime, knew his imprint sat on the chopping block so he wrote a letter to leadership at the major label, imploring them to spend money getting his band in the studio – preferably not in Southern California.

"I was trying to get the band out of Long Beach because there were distractions here," reveals Phillips, citing wild social lives and substance abuse issues already causing Nowell legal trouble.

Sublime began recording its big label bow in Redondo Beach, Calif., with Grammy-winning producer David Kahne. Initial sessions yielded "What I Got," "April 29, 1992 (Miami)," "Caress Me Down," and "Doin' Time," but sessions aborted over interpersonal friction. Enter Leary, summoned to Long Beach for pre-production the band blew off prior to scheduled studio time in Texas.

Sublime first gigged Austin in 1991 at Mercado Caribe on Sixth Street, playing with locals I-Tex, which featured future Mau Mau Chaplains leader Alan Moe Monsarrat, whom Wilson remembers as "a cowboy-lookin' dude who played bass and sang roots style reggae." The trio also triumphed at South by Southwest 1995, playing a 1am Sunday slot at the White Rabbit Lounge that turned into an after-hours encore and landed Sublime on the cover of USA Today.

"Instead of flying out there to record, we got an RV and played shows on the way down," Wilson recollects.

Leary remembers Sublime's arrival at Pedernales. "There's a very steep driveway that leads up to the studio and their long, dilapidated RV got stuck on the hill," he laughs. "I went out to meet them and they had all their dogs with them, even though I told them not to bring them. They weren't going to go anywhere without their dogs."

Like A Motherfuckin' Riot

"It was obvious to both of us early on that this band was fuckin' amazing," reports veteran Austin studio sage Stuart Sullivan, who engineered the album. "Bradley was certainly exceptionally talented, but Eric and Bud [Gaugh] were a major groove. Together, as a band, they were something else."

As such, the locked-in trio provided abundant magic to capture on reel-to-reel. In fact, a surprising amount of what you hear on Sublime came from live tracking – even some of Nowell's vocals and guitar solos.

"They were just that good," Leary allows. "Occasionally, though, their songs would be too long, but at Pedernales they had a golf course. They'd record a nine-minute song and I'd send them off to go play a round of golf. When they got back, it was a three-and-a-half minute song and there'd be a pile of tape on the ground."

Wilson remembers that Gaugh and Nowell flipped a golf cart and hit one of Willie Nelson's friend's houses with a ball.

"Those guys were terrible at golf," laughs Happoldt. "Just the worst!"

While grooved-out reggae and surf punk came easy, words didn't. Lyrics that feel iconic today were sourced largely off-the-cuff and spliced together. All agree, though, that Nowell demonstrated immaculate delivery and pitch.

"Brad wrote the first two albums lyric first, then got away from that," explains Happoldt, whose Sublime LP credits include guitar, vocals, and Space Echo dub effects. "I think a lot of it was his drug use. He couldn't zero in on anything. So he'd fill up every track with freestyles and Brad was like a fountainhead, never ran out of ideas, but a lot of it was gibberish.

"He'd say, 'I'm gonna go home and write lyrics for real,' but Paul was smart enough to say, 'No, you're not.' Then he and Stuart would comp the gibberish into a real song, which must have taken hours."

On one occasion, they cut together such an outrageously pornographic vocal composite that Nowell became mortified and volunteered to record new lyrics immediately. Leary kept microphones ready around the clock, not just for lead vocals, but also a setup for acoustic numbers, none of which made the final sequence as Nowell originally intended. Instead, they amassed dozens of songs that eventually emerged on posthumous collections – an impressive number considering the band's level of inebriation.

"One day, they came to me looking all concerned and I thought there was a problem," Leary recalls. "They said, 'We start recording at noon and we're already drunk. We need to start earlier in the day.'"

Accordingly, Sublime and the studio team resolved to start sessions in the morning. "So I get there early the next morning and they show up with pitchers of margaritas in hand – already drunk," Leary continues. "It didn't matter what time you started, they were gonna be drunk."

Under My Voodoo

"At the time, we had a white Suburban and we let Sublime use it," recalls Lisa Fletcher, who operates both Pedernales and Arlyn Studios. "On the second day, they crashed it. It was so adorable because they were scared that we were going to be mad. We never even fixed it. We liked that we had a Sublime dent."

While Fletcher warmly refers to Sublime as "those precious boys," others might've called them walking liabilities. Their string of snafus at Pedernales included accidentally starting a fire in the pool area, getting kicked out of their condo because of the singer's dalmatian, Louie, and Wilson's basenji, Toby, raising hell, and Nowell scribbling an unfortunate mustache on a 1984 poster for Willie Nelson's 4th of July Picnic.

"I came in and Bradley had taken a sharpie and drawn a Hitler mustache on Willie," Leary recounts. "I fuckin' lost it. It almost came to an end right then and there. Miguel calmed me down and said he'd fix it."

Happoldt, who maintains the frontman attempted Charlie Chaplin facial hair, rectified Nelson's upper lip using supplies he found in the repair shop.

"Yeah, it was one thing after another, but I don't think we were that bad," he assesses. "We just had a lot of fun and we got a lot of great music done."

While rips out of Sublime's spill-proof bong were enjoyed by all, extracurricular drug use threatened to derail productivity.

"They showed up to Pedernales with enough heroin to last for the entire duration ... and it was gone in less than a week," estimates Leary. "So they sent someone back to California and bought so much that the dealer threw in an 8-ball of coke. That really amped it up."

Wilson distances himself from the drug combo plate: "We weren't really doing all the stuff that Brad was doing. For the most part, we just smoked pot and drank beer."

At the sight of injectables, Leary became conflicted over whether he should leave the job, but he knew the other bandmates and family members counted on this album, so he resolved to keep an eye on Nowell, which meant occasional life-checks in the bathroom. Sullivan believes the great degree of chaos surrounding the Sublime sessions triggered Leary's super powers as a producer.

"Paul has this skill to see and capture brilliance as it runs around in the room," he explains. "That's exactly what was going on with Sublime: There was one crisis after another and stresses and pressure and Paul managed to grab the right pieces and that's why it sounds effortless. That's one of Paul's magic tricks and it's on full display with that record."

Leary downplays his role in shaping Sublime, insisting he simply viewed producing an album like taking a photograph of a band. In fact, he credits Sublime with providing him a valuable learning experience.

"I used to bring a stopwatch to see if a band was speeding up or slowing down," he reveals. "But Sublime sped up and slowed down throughout their songs. That's just what they did. Eventually, I learned to listen to what was good. That was a big step for me."

The Wrong Way

While memory obscures an exact timeline, several involved believe that after Pedernales, Sublime adjourned from recording to play shows – including the South by Southwest High Times party at Emo's – then Wilson and Gaugh flew home, while Nowell and Happoldt settled into Arlyn for overdubs, additional vocals, and turntable work from Marshall "Ras MG" Goodman.

Inspiration still abounded: When Sullivan and Leary threw out the half-joking idea of adding trombone to "Wrong Way," Nowell enthusiastically green-lit it. So Sullivan called his friend Jon Blondell, who arrived and transformed the track with a brilliant solo.

"There are great musicians and then there are people who can do anything. Blondell is one of those guys," Sullivan confirms. "How crazy he'd be in the process was the only question."

When the Austin instrumentalist made a stink about having to wait for an MCA payment, Leary coughed up his brand new Tag Heuer wristwatch to appease him. Meanwhile, Louie the dalmatian got booted from another hotel and had to be flown back to California in a crate. Happoldt says that "let the air out of Brad's tires" and any maintaining he'd been doing went out the window.

"He went to Mexico, brought back a bunch of Valium, and was all fucking blooped-out on that shit," Wilson explains.

Sullivan buries his frustration in sarcasm: "Heroin and valium – that was a very productive combination."

Phillips counts that moment as Nowell's "all-time low." His hotel faxed the label gnarly damage reports over the room's druggy disarray. Lisa Fletcher also confirms that her cleaning crew at Arlyn became concerned over needles. A couple weeks into the second set of sessions, Leary had had enough.

"He needed help and I wasn't gonna watch him die in the studio in front of my eyes, so I pulled the plug," remembers the producer. "Bradley came out of the bathroom ... I can't even tell the story because it's so awful ... and he wanted to show me where he was shooting up. That freaked me out. I said, 'It's over,' and he got mad and fired me."

Given the Butthole Surfers' wild and woolly history, Leary maintained an acute knowledge of opiate addiction, so Phillips took it serious when he balked. He told Nowell to come home – and also got fired on the spot.

The following day, Nowell told Leary he understood. Happoldt got him on a plane, allegedly attributing the singer's pronounced track marks to an injury incurred from bees. According to Phillips, he entered treatment upon return and seemed focused on staying off hard drugs.

Looking back, Happoldt revisits his rationale for wanting to complete the album, despite his best friend's worsening addiction. "It was a nightmare, but it was everything we'd worked for and I was hoping that turning in a good record would set us up for Brad to get the help he needed," he explains. "I went to sleep every night telling myself that."

Same in the End

Paul Leary was playing a festival in Belgium with the Butthole Surfers when he got a call from his first wife telling him Bradley Nowell had died.

"It was such a bummer," Leary says, sorrow in his voice. "I wasn't surprised because when I said goodbye I felt like I'd never see him again. It was really sad that was the case."

May 25, 1996, Gaugh found Nowell cold on the floor of a San Francisco motel room. Heroin. Less than two months after leaving Austin, he'd recovered from his out-of-town bender, gotten married to his longtime girlfriend, and set off on tour. He was just 28. His son, Jakob, hadn't yet celebrated his first birthday.

Phillips remembers the singer feeling unsure about the new album upon his return from Austin, telling him, "I don't know, it's not [1992 Sublime debut] 40oz to Freedom." Nowell wanted the manager to help him get to Jamaica to record, but when the former received a "Santeria" mix, via cassette, from Leary, he recognized a hit album immediately. Not that the struggles to make the record were lost on Phillips.

"The fact they made that timeless music in a situation that was less than desirable because of substance abuse and got it done was a miracle," he says. "It was a race against the clock. Your superstar has a monkey on his back and no one knows how to deal with that."

Meanwhile, the enormous and continuing success of Sublime – rivaled only by the (formerly Dixie) Chicks' Home as the top-selling album recorded locally – reaffirmed that massive albums could be made in Austin, which made Sullivan proud.

"I have so much happiness from that record: the music, the friendships I made, and, I won't lie, the excitement of having a record that I could go buy Billboard magazine every week and see where it was at [on the charts]," he relates. "The record has so many positive aspects and it's such a wonderfully reminiscent experience that I can forget a lot of the damage that came from it."

Paul Leary on Sublime:

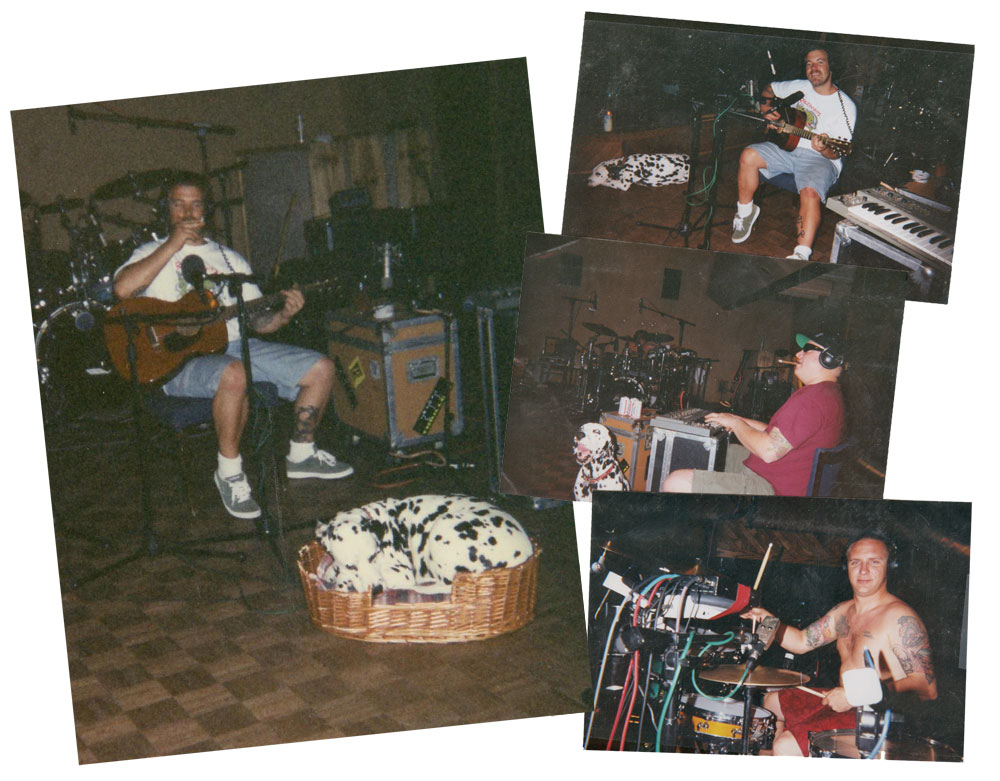

Nowell (top, left): "Brad was a fantastic guitar player. He could play the songs live so beautifully and so perfect"

Wilson (center): "I love Eric. He's probably the most interesting musician I've ever worked with." [the two continue to collaborate frequently, including on a forthcoming album by WIlson's new band Spray Allen]

Gaugh (bottom): "A really special drummer - has a way of hitting the drums just right. He was set up in front of the control room so I was looking at his butt crack the whole time."

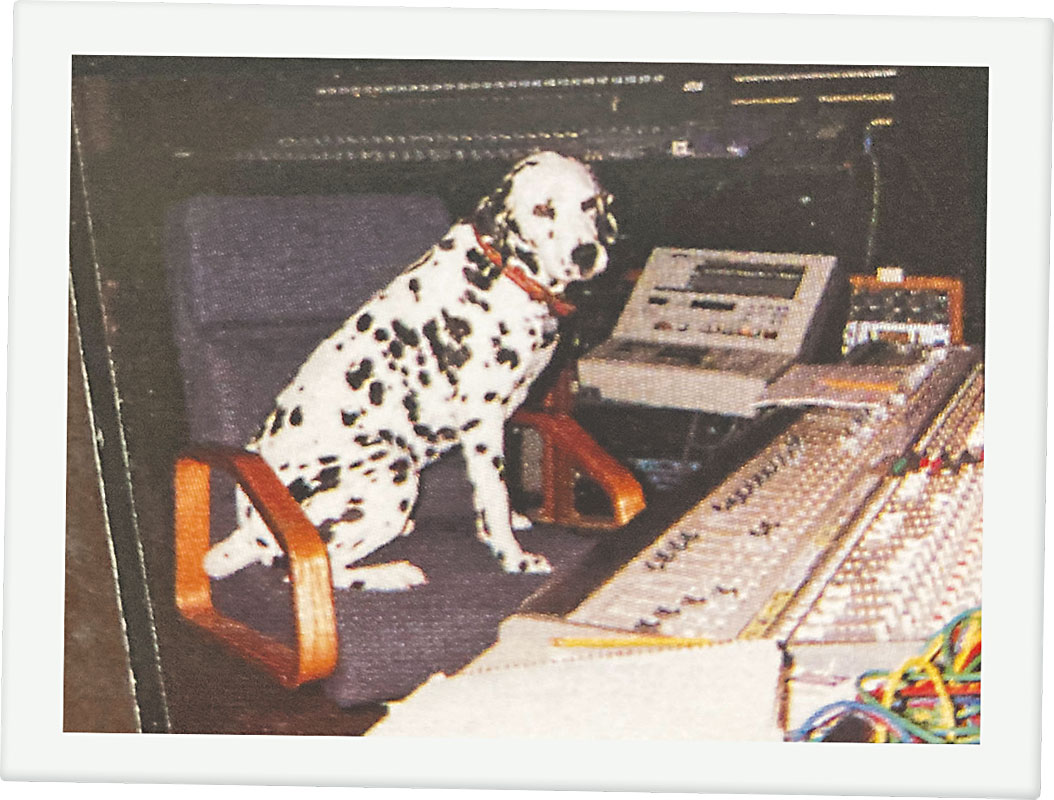

Down Here at the Paw'n Shop

"[Nowell's] favorite thing to do was to grab Lou Dog by the tail and yell my name and when I'd look he'd stick his thumb right up the dog's butt." - Paul Leary

Learn more about Sublime’s canine companions at austinchronicle.com/music