Do Right Woman

Calling Polly Parsons home to the Hickory Wind Ranch

By Margaret Moser, Fri., July 31, 2009

Polly Parsons' late-model Maxima rolls up under the iron Hickory Wind Ranch sign. The storm-gray car noses up the driveway to a vacant house with a few stray chairs out front and stops, the driver smiling at the woman beside her.

"You know what this place reminds me of?"

Shilah Morrow, Parsons' lifelong friend sitting in the passenger seat, tips her cowboy hat and nods toward the house. "Joshua Tree Inn."

Sitting in her California living room on Sept. 19, 1973, Parsons was 5 years old when the news of her father's death at the Joshua Tree Inn came on the television. Gram Parsons, 26, shone among the most brilliant stars in the rock firmament, and his career went down in a blaze of recorded glory, a light snuffed by a drug overdose. The father she hardly knew left a legacy that's taken his only child a lifetime to decipher.

Parsons turns her face to the unprepossessing porch. Her ice-blue eyes linger on it, the summery flowers pinned in her red hair giving her a pre-Raphaelite quality. She nods slowly, hands relaxed on the steering wheel.

"Doesn't it? I thought that, too."

Ride Me High

It's not that rock & roll wasn't thinking about country music in the 1960s, just that no one thought about it the way Gram Parsons did. The nature of Top 40 radio always allowed for country hits; the Beatles picked 'n' grinned through Buck Owens' "Act Naturally" as the B-side to "Help" in 1965, the same year the Byrds recorded Porter Waggoner's "Satisfied Mind." The Monkees' eponymous 1966 debut fiddled "Sweet Young Thing," co-written by Texan Mike Nesmith.

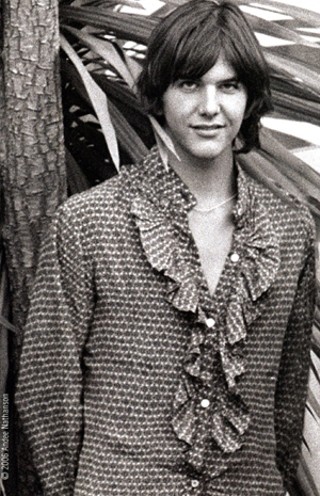

Gram Parsons came by his country music naturally. Born Ingram Cecil Connor III in Florida on Nov. 5, 1946, he was raised in Georgia by a wealthy orange-growing family. Young Gram, whose name changed to Parsons when he was adopted by his stepfather at 12, showed an early interest in music, forming various high school combos.

During college, his folk band the Shilos did a stint in Greenwich Village, whetting his appetite for the stage. He skipped out of Harvard to play Cambridge and wound up forming the International Submarine Band in New York City. Gram soon navigated the Subs to California, where they floated a country rock disc then sank. By now, he knew country was his calling. In 1967 he became a father.

Gram flew free and easy in mid-1960s L.A., flocking to the Byrds with the seeds of 1968's seminal Sweetheart of the Rodeo, which featured veteran Nashville sidemen such as Earl Poole Ball and John Hartford playing standards from the Louvins and Woody Guthrie. Included with Gram's own "One Hundred Years From Now" was the song that became his anthem, "Hickory Wind."

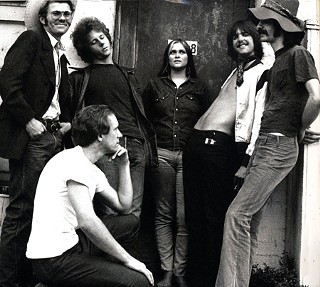

The country backbone of Sweetheart of the Rodeo came largely from Parsons and fellow Byrd Chris Hillman, also a new member. The two mixed formidably with head Byrdman Roger McGuinn, a schooled folkie who fully appreciated their roots-driven direction. Feathers flew among the Byrds on tour in Europe, especially after Gram and Keith Richards hit it off, and Gram flew the coop.

The friendship between Richards and Parsons flourished, a gruesome twosome who inspired and encouraged each other's muses and shared a propensity for the wild side of life. They smoked, drank, played, and bonded all over the map, from Europe to Joshua Tree in the California desert. The next time the Rolling Stones – always the mirror and never the face – recorded, they brought steel guitars and fiddles to the Beggars Banquet.

Sin City, Las Vegas, and the Streets of Baltimore

Parsons wasn't the only ambassador of country in 1968 – Doug Sahm appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone wearing a cowboy hat that year – but Gram got to the Grand Ole Opry first with the Byrds.

While Sahm was grooving in Mendocino, Parsons rounded up the Flying Burrito Brothers with Chris Hillman. Armed with a purer vision of country than the folk inflections of the Byrds, the group's 1969 debut, The Gilded Palace of Sin, was laden with soul standards such as "Dark End of the Street" and "Do Right Woman," but no one was prepared for the originals that the Parsons-Hillman pairing delivered.

"Sin City," "Wheels," and "Juanita" crackled with life, woven crisp and sewn tightly with the threads of rock and country. Parsons wrote with Burrito bassist Chris Etheridge ("Hot Burrito #1") and Barry Goldberg ("Do You Know How It Feels") as well as Hillman, but Gilded Palace was unquestionably Parsons' claim to stake, because by their subsequent album, 1970's Burrito Deluxe, his molten energy had dissipated. He still twinkled in the Nudie jackets he'd outfitted the band with and scored a coup by recording "Wild Horses" before the Stones did, but Gram left the Burritos before Deluxe was served to the public.

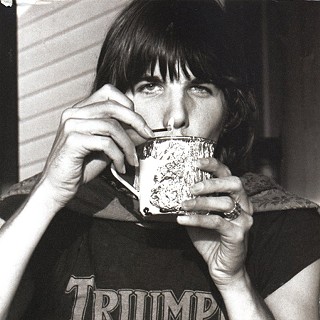

Parsons spent 1971 thinking about his new direction, much of it with Keith Richards in the frenetic Rolling Stones camp in the south of France, where Exile on Main Street was being recorded amid predictable excesses. His family wealth bought him the freedom of not having to work. It also allowed him to reach into his creative heart unfettered.

The experience of writing his own music intoxicated Parsons, but he craved a voice to complement his serviceable twang, a Tammy Wynette to his George Jones. He found it in Alabama-born folksinger Emmylou Harris, their voices twining eternal, like ivy and oak. Parsons signed to Reprise and with Harris recorded GP in 1972 for release early the next year. GP was a glorious debut, as electrifying as Gilded Palace, just as groundbreaking and equally ignored.

It made Emmylou Harris an instant star and established Gram as a bandleader. His songwriter status needed no affirmation, yet these songs were visceral, naked breakup originals like "How Much I've Lied" and calico confessional "We'll Sweep Out the Ashes in the Morning" accompanying the Glaser-Howard favorite "Streets of Baltimore." Parsons quickly assembled the Fallen Angels, including steel player Neil Flanz, who lives in Austin, for a spring tour that included a stop at the Armadillo World Headquarters on Feb. 21, 1973 (see "Man Mountain and 'Sin City'").

The local stopover included a notorious incident in which Parsons and Harris took umbrage at a question about their progressive country affiliation during an on-air interview at KOKE FM. Both the station and deejay Rusty Bell pioneered country rock radio and were kindred spirits to Parsons' music, so the real cause of the incident remains a mystery. Parsons and Harris denied being "progressive country" – she claimed they were "regressive country" – and both stomped out of the studio.

GP was indelible, but Grievous Angel, its follow-up, was the reckoning. It still glistens with steel and heartbreak fiddle, a flashing moment of brilliance that spun Gram Parsons' wheel of fortune into infinity. The gorgeous "In My Hour of Darkness"; exuberant "Ooh Las Vegas"; sad, autobiographical "$1000 Wedding"; and wistful "Brass Buttons" preserve its magic, which he never lived to enjoy.

Released in 1973, just weeks after his death, Grievous Angel capped an amazing output that also recorded its creator's development as a songwriter and champion of a genre suddenly in vogue. That Gram Parsons was ahead of his time remains a given.

"And he made all that music in five years," nods Polly Parsons with a tone of incredulousness. "Five years."

Hour of Darkness, Time of Need

"His name was forbidden in my home, his music forbidden."

Polly Parsons, sitting in the kitchen of her Austin home, lets her gaze wander from the multitude of family photos on an adjacent wall to the square green iridescent tiles on the table in front of her. The images pay tribute not only to Gram but also to generations of movie-star handsome Connors, Parsons, and Snivelys, as well as Polly's husband, artist-musician-concert video designer Charlie Terrell, and their daughter, Harper Lee.

Children of the famous carry a peculiar weight. Children of musicians shoulder a different kind of burden. Children of famous musicians carry the toughest load of all.

"I was sitting on the living room floor, and it came on the news," recalls Parsons. "I immediately went to find out what was going on. I was told a different story every month for about six months – told he died in a fire, he had a heart attack. ... After he died, my mother had a real hard time. We went from commune to commune to commune to commune to commune. She never married and mourned the death of my father more than the life of me. She got sober when I was 14, but by that time it was too late. She was alive and alert, but I was in pain and pissed off.

"By 16, I became horribly addicted to cocaine and alcohol. I never mentioned who my father was, so no one knew until I was about 25. I was terrified that my outcome would be written in stone if I acknowledged the fact that I came from people that couldn't manage to stay on the planet. That's what my lineage was.

"Finally, I got to discover him by myself, on my own terms, and it wasn't pretty. I locked myself in a room, and I listened to everything, and I wrote down everything in journals. I prayed and cried and ripped things up, and 12 days later I came out of that room like: 'Okay. I'm ready.'

"I was about 32."

She used her father's renowned repertoire to take her life in her hands. Not only did she seek control of her heritage, she wanted to experience it fully, so Parsons wrote, performed, and toured in the 1990s. Her star-studded concerts attracted the musicians Gram Parsons influenced heavily – Lucinda Williams, Dwight Yoakam, Norah Jones, Steve Earle, even Keith Richards. In 2004, she produced concert DVD Return to Sin City: A Tribute to Gram Parsons. Two years later, on a whim, she bought a house here in Austin.

"What was it that made musicians like my father spin out of control?" she wonders. "I don't know the answer, but look at how bright their fires burned right before. My father, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison ... they produced an outpouring of jet-fuel-like passion. My father wrote a body of work from 21 to 26 on fire, so I go back to what was happening the moment they went down and how incredible their output was. How do you tie that into a neat little bow in the end, or do you just burst into firelight?

"I knew I could not go forward without coming to terms with who I was and what that meant. How would I take the beauty of the truth, without tarnishing it or embarrassing myself, so I could perpetuate his legacy properly with love and respect? How was I going to come through it and not just recycle the history of my past? My grandfather shot himself in the head, my father's mother died of alcohol poisoning, and my mother's mother committed suicide in our backyard two weeks after my father died.

"I sit here in the aftermath of complete Hiroshima destruction."

Oh Lord, Grant Me Vision

"There's a very happy story on the other side of the wall from drug addiction," offers Polly Parsons, rising from the table and readying for a ride next door.

She's referring to her own recovery, complete with relapses, but in a larger sense, she means Hickory Wind Ranch (www.hickorywindranch.com), a sober living environment she's created for women in entertainment and the arts who are in recovery from alcohol and drugs.

Her own sobriety is as important to her as her husband and child and their home, something she protects fiercely. Yet she's not proselytizing or preaching, and as she drives to the adjoining property, she reiterates the need for a comfortable, controlled, zero-tolerance atmosphere.

"I was supported artistically early in my sobriety," she stresses. "Writers and artists were all around me. I had faith it was working for them even if I didn't think it would work for me. So the idea is there really is hope, that if you're in a sober living situation in the language that you speak, you have a fighting chance."

With its facade resembling the premises where her father took his last breath, the ranch house's shared rooms offer women personable quarters under a program that reteaches everyday life skills under supervision and amid random drug testing and regular 12-step and recovery meetings. Parsons gives a guided tour, free-associating along the way.

"My story is I am the daughter of a musician and a woman in an industry that's largely misunderstood in general and one that feels like it needs to be inebriated to create. Women have unique challenges as artists, as musicians, that are intimate and personal and ethereal and not necessarily understood. And if we don't create, our spirits die, so if just one girl or one woman walks through these doors and is able to survive another day, that's enough.

"When it comes to my father, I was in denial for so many years about who I was and who he was and what he meant and how I could live up to that. For years, I was angry and hurt and pissed off, then I came full circle. 'Polly Parsons, do you think it's absolutely morbid that your father was taken into Joshua Tree desert and his body burned by his road manager/best friend?'

"No! As a matter of fact, I think that's so righteous! Right on! God, I hope that I die with people who love me enough to carry out my crazy wishes! I'm glad! And when it came to being my father's daughter, I realized that truth be told, I'm just the luckiest Gram Parsons fan. I'm just as passionate about his music today as when I was 12 and it was forbidden in my home."

She stops outside the bedrooms, the only spaces not furnished, and surveys them one last time. Hickory Wind isn't a nonprofit, and funds are stretched tight. "Right now, what I need is to get beds and linens. When that happens ..."

Callin' Me Home, Hickory Wind

Having Polly Parsons' words read like bumper stickers or a T-shirt isn't a stretch in the realm of recovery. To a degree, all the language employed in such endeavors can sound somewhat pat. There's a reason for that, however: Words work. Yet while 12-step lingo is crucial to the recovery process, Parsons found that too much self-examination can sometimes be more harmful than helpful.

"Life has the elements of a battle, but with each new challenge comes a new discovery," she explains. "When I'm cut off from the emotional core of my being, whether I'm taking Tic Tacs or heroin, it's only a matter of time before I'm disconnected from everything else."

She's talking about her relapse more than a year ago, a slip that began with a desire to be a good mother. Her doctor prescribed her Xanax, and all too soon Parsons found herself effectively off the wagon.

"I had so much time in sobriety – chips, cakes, anniversaries – now through the back door came doctor-prescribed medication. Whenever an alcoholic or drug addict takes a substance that tries to alleviate feelings, they're no longer sober. I had issues about my father and mother. The more things that came up in therapy, the more confused and depressed I got. And I found out there are some things you don't need to know.

"I really believed I was doing the right thing, that to be a good mother I had to deal with my past regarding motherhood. What I found out is that I am a good mother. I've broken the cycle of abuse, and I don't need to know how bad it got. But my brain – just like every other addict on the planet – says that if I'm being prescribed medication by a physician, he must know what he's doing. It was not the right path for me, so once again I started over.

"I started taking pilgrimages to Joshua Tree by myself, with the memory of my father, and I made it personal. I started doing the things I had to do to grieve and mourn and come out the other side hopeful. I will never be able to repay the debt to my father, so this is my way of staying close to my heritage and my roots. This is me trying to be a better friend and face a really big shadow, ghost. Very big, but I don't feel anything but love. He is one of the most active spirits I've ever come across. He is right here, right now.

"There's a line he wrote, 'Callin' me home, hickory wind.' It talks about where we go when we're lonesome. I miss him profoundly. Deep down, I believe the thread between life and death is very, very thin, and I don't think he's farther than my prayers. I really feel that he's as close as I need him to be, emotionally and spiritually.

"I'm just his little girl, doing the best I can."

Angels, Grievous and Otherwise

The e-mail came late that night, forwarded from Parsons. The subject line read "Gram Magic" and serves as a reminder that angels do sometimes have dirty faces.

"Ladies, Keith Richards just sent a donation to cover the girls' beds and linens. Is that just too much or what?"

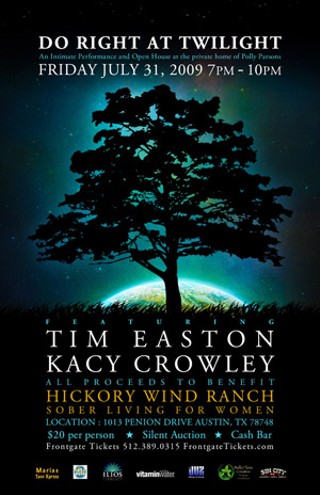

Do Right by Twilight

Friday, July 31, 7-10pm

Celebrating the opening of the Hickory Wind Ranch Sober Living Environment, Polly Parsons is throwing a Do Right by Twilight house concert with all proceeds going to HWR, located at 1013 Penion Dr. The show features Tim Easton and Kacy Crowley, plus a silent auction and cash bar. Tickets are $20 through www.frontgatetickets.com.