The Mother of All Texas Honky-Tonks

Live at Gilley's

By Christopher Gray, Fri., Oct. 15, 1999

About an hour into Urban Cowboy, Scott Glenn is explaining to Debra Winger the intricacies of worm swallowing. "Mess-kins say eatin' the worm'll give you visions," his ex-con rodeo rider Wes Hightower says, repeating a hoary tequila legend. "They call it "livin' la vida luna' -- the crazy life." Which is essentially what the 1980 Paramount Pictures smash was about: trailer-park days and honky-tonk nights. It's fitting, then, that nearly 20 years later, during the international year of "Livin' la Vida Loca," the gargantuan Pasadena, Texas, nightclub in which most of Urban Cowboy was filmed -- Gilley's -- is itself enjoying a bit of a renaissance. Q Records, the recording arm of home-shopping conglomerate QVC, began issuing its Live at Gilley's series this summer, recordings of Carl Perkins, Fats Domino, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Paycheck, the Bellamy Brothers, and Bobby Bare, all taken from the club's stageside 24-track. Followed last month with live performances from Mickey Gilley and Johnny Lee, the collection also includes a 4-CD box set that features Mel Tillis, Faron Young, Ernest Tubb, Moe Bandy, Ed Bruce, and Willie Nelson, among many others, which came out at the end of 1998. In other words, if anyone in country music over the age of LeAnn Rimes wants to release a live album, all they have to do is sign a release form. Seems that 10 long years after it went up in flames, Gilley's is very much alive. And yes, it's been quite the "vida loca."

Ballad of the Urban Cowboy

Once in the Guinness Book of World Records under "World's Largest Night Club," Gilley's burned to the ground in July 1990. By that time, the glory days of the fabled saloon at 4500 Spencer Highway were long since past. Mired in property and school-district taxes, the club had been closed since March 1989. Before that, its luster had been dimmed considerably by a bitter feud between onetime partners Mickey Gilley and Sherwood Cryer, who once agreed to split everything the club made 50-50, and wound up agreeing on not much at all. To top it off, Gilley's was located at ground zero of a devastating early-Eighties oil bust, something Pasadena -- a blue-collar patchwork of strip malls, subdivisions, refineries, and pipeline immediately southeast of Houston -- felt even more acutely than the rest of the Greater Houston sprawl.

In its prime, however, way before John Travolta uttered "up ya nose witta rubba hose," Gilley's had a reputation as the mother of all Texas honky-tonks. The Gilley's logo adorned everything from cans of beer (brewed by the same Spoetzl brewery that brings us Shiner Bock) and belt buckles to women's silk panties. Texans and tourists alike would cram in by the thousands to see top country music stars like Willie Nelson, Loretta Lynn, and George Jones, while a hardy, colorful crew of regulars (known locally as "Gilleyrats") showed up every night to drink, dance, fight, flirt, make out, bullshit, shoot pool, and see who got their nuts cracked on El Toro, the club's famed mechanical bull.

"It was the wildest, most fun place that you could go to, and you could do just about whatever you wanted to," says Johnny Lee, whose song "Lookin' for Love" was a # 1 country hit off the Urban Cowboy soundtrack as well as one of the film's signature songs. In his 1980 book Saturday Night at Gilley's, now-deceased Houston Post pop music critic Bob Claypool wrote: "It was, quite simply, the most Texan of them all, the biggest, brawlingest, loudest, dancingest, craziest joint of its kind ever."

More than any other institution of its era, Gilley's said "Texas," and the word "Gilley's" appears onscreen in Urban Cowboy at least 100 times. The bulls were mechanical, but the story could have just as easily happened in the Fort Worth of 1878: Cowboy comes to town looking for work, lives it up at local saloon, marries sweet young thang he meets on the dance floor, and lives happily ever after a few fights and a climactic, manhood-affirming test of cowboy skill -- in this case, the mechanical-bull contest. But Urban Cowboy said "Pasadena" just as much. Warehouses, doublewides, and malls became the new sagebrush, bunkhouses, and trading posts of Texas.

The media-driven mania for all things Lone Star, building throughout the late Seventies thanks to ZZ Top, the Dallas Cowboys, and Farrah Fawcett, plus Waylon & Willie and all the havoc they wreaked, reached a fever pitch upon Urban Cowboy's release. Overnight, the backward, vulgar, pickup-driving hicks who killed JFK and unleashed LBJ on the rest of America became freewheeling, smooth-dancing rogues, whose devil-may-care attitude -- not to mention overflowing petrochemical resources -- rendered them immune to the prevailing economic and social malaise of the late Seventies.

Texan-gone-New-Yorker Aaron Latham touched the whole thing off with an article called "The Ballad of the Urban Cowboy and America's Search for True Grit" in the September 12, 1978, edition of Esquire, in which he called the cowboy America's "most durable myth." The new Neal Cassady was Dew Westbrook, a 28-year-old foam-glass sawer at Texas City Refining. Soon, hipsters who previously would have rather eaten glass than come within a mile of anything "country" decked themselves out in fleece-lined denim jackets, Wranglers, and shitkicker boots; Gilley's line of designer jeans gave new meaning to the words "cover charge." Artists who played the club, like Lee, Gilley, and the Bellamys, found themselves contending with Michael Jackson, Blondie, and Air Supply on the pop charts, while dance floors coast to coast resounded with cries of "Bull-shit!" as non-Texans from Tucson to Toledo lined up to learn the two-step and Cotton-Eyed Joe. Manhattan's Lone Star Cafe was a place to see and be seen, and Yankees were rumored to be dropping "youse guys" in favor of "y'all."

Public fancy eventually drifted south of the border, but the refineries stayed put. For those who punched in and out five or six days a week at the nostril-clogging plants around the Ship Channel and Galveston Bay, their lives were now as much a part of Texas' mythic tapestry as the ones depicted in Giant, The Last Picture Show, or Red River. Meanwhile, the iconic red script of Gilley's sign was more recognizable than the nearby San Jacinto Monument. Maybe that helped ease the sting when thousands were laid off after the price of oil crashed. Probably not. But what's the first thing you want to do when you lose your job? Get "drunker 'n Cooter Brown," as Winger says to Travolta not long after he slaps her the first time. Gilley's never had much trouble with Pasadena city officials. "They was out there livin' it up too," says Cryer.

For a while, that was enough. Gilley's stayed open long enough to host up-and-comers like George Strait, Randy Travis, and the Judds, but over time it lost its shine. By 1987, Gilley had filed suit against Cryer. He wanted his name off the club and the money he claimed Cryer owed him.

"One time," remembers Gilley, "he had a little sign that said, "Check your guns, your knives, and your knucks.' I said, "Hey, man, that's not funny,' and he said, "Well, that's just a joke.' I said, "That's not funny.'

"It got real rough."

For his part, Cryer says he always paid Gilley in cash and that Gilley lied on the witness stand. Gilley says Cryer is a liar who doctored his contract. The jury believed Gilley to the tune of $17 million. They've put their legal differences to rest, but the personal rifts remain.

"When I finally heard it burned down," says Johnny Lee, "I was so pissed off at [Cryer] that I really didn't give a shit."

Room Full of Roses

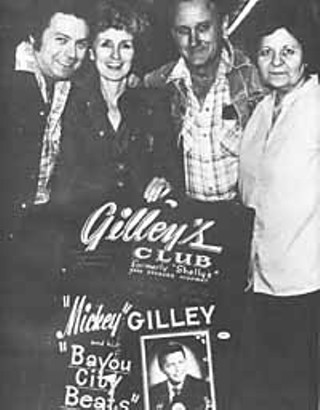

Gilley's wasn't always huge, as cultural dynamo, nightclub, or albatross. It wasn't always called Gilley's, either. It came into existence in 1971, when Cryer was already ensconced on the property running a beer joint named Shelly's.

"It was an open-air affair, and made big money," explains Cryer. "Hell, I had all the stars -- Willie Nelson when he was still runnin' a three-piece band, Roy Acuff, George Jones. Used to get him for $250 a night. So it rocked along there for several years. I wasn't settin' the world on fire, but I was bringin' in country music."

This included a barely post-pubescent Hank Williams Jr.

"He had his mother Audrey with him," remembers Cryer, "and since the place wasn't air-conditioned, and it was hot, we put him in the beer vault, and he got drunk on Pearl beer. Boy, his momma whupped his ass bad over his gettin' drunk."

Cryer thought having a singer on a regular basis might be better. Mickey Gilley, whom he first saw at the Nesadel Club about a mile east on Spencer, needed a gig. Their new enterprise needed a name. Gilley suggested "Den of Sin."

"That was a joke," says Gilley. "I said, "I don't care what you call it, you can call it the Sin Den if you want to. He said, "Let's call it Gilley's.' I said, "That's a great idea.' I'd never call something the Sin Den if I was going to be playing there."

"[Gilley] said, "Well, the only way I'd come out here is if you bulldoze this whole place down' -- it was made out of metal -- "and build a new place,'" recalls Cryer. "I said, "No, I'll air-condition the place and I'll start advertising you, and we'll try to make it go.'"

Whether it was the air conditioning or hot house band the Bayou City Beats, whom Gilley fronted with a Panhandle-wide grin and a repertoire spanning fiery, piano-pounding rockabilly and shimmering pop standards, the club began filling up like a holding tank at the looming refineries. Helping spread the word were Gilley's weekly television show on an independent Houston channel, a steady barrage of radio spots on FM country giant KIKK, and the red-and-white Gilley's bumper stickers that soon rivaled "Proud to be a KIKKer" for pickup-truck dominance. Before it was all through, there would be a 10,000-seat rodeo arena in addition to the club and a nationally syndicated Live at Gilley's radio program on the Westwood One network that ran until 1989.

"You couldn't drive a Houston street for long without coming across the ubiquitous Gilley's bumper sticker," wrote the Houston Post in a valedictory July 9, 1990, editorial. Turns out, a fateful visit to Atlanta in 1974 had revealed another potential source of revenue.

"I went and played the Playboy Club," Gilley says. "Mr. Cryer went down there with me, and he saw the little bunny head, all different paraphernalia they were selling in there, and it was just souvenirs. We started off with T-shirts, then went to the caps, and then I started adding different items. By the time Urban Cowboy came along, we had a full line of just about everything you could think of with "Gilley's' on it."

Also in 1974, Gilley realized a lifelong dream, scoring his first hit single. "Room Full of Roses," a poignant ballad rife with Reevesian heartbreak, was originally recorded as a favor to Cryer's assistant Minnie Elerick so the club's patrons could play a Gilley record on the jukebox. KIKK got interested, and eventually the song broke all the way to Number One.

"I first heard the record under the best possible circumstances,"writes Claypool in his book, "barreling down a slick Houston freeway in a wee-hours rainstorm -- with maybe one too many Lone Stars under my belt. On nights like that, truly fine country songs have a way of leaping out of the radio."

With "Roses," Gilley was off and running. Subsequent hits included, "I Overlooked an Orchid," George Jones' "Window Up Above," and "Don't the Girls All Get Prettier at Closing Time," which won the CMA Song of the Year award in 1976. The singer went from opening for Conway Twitty and Loretta Lynn to co-headlining shows with them. He also went from playing six nights a week at Gilley's to touring for months at a time.

"I bought Gilley an airplane," recollects Cryer, who was then Gilley's manager and also handled Johnny Lee's affairs. "And every time he'd have a number-one song, I'd buy him a big diamond ring, because we were making money out there at the club."

Through Gilley's efforts, urging crowds to "come see us if you're ever in Pasadena," more and more non-Houstonians began driving out to Spencer Highway. At one point, more people visited Gilley's than the Astrodome, but then the Astros and Oilers weren't burning up their respective sports in those years. The number of locals kept rising, too, and Cryer was constantly adding onto the property, trying to keep capacity up with demand. He eventually started up another club down the road apiece (in the old Nesadel building) and named it Johnny Lee's.

"Sometimes I'd play one set at Gilley's, then I'd drive to Johnny Lee's and play a set there," laughs the club's namesake, who'll be inducted into the Texas Country Music Hall of Fame in February. "Then, I'd drive back to Gilley's and play another set. I was on the road all night."

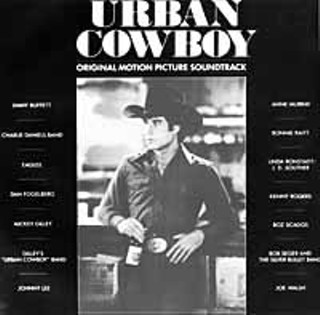

Mickey Gilley's newfound stardom in country music had its own complications, in that his music was country only so far as country itself was assuming new identities around this time. The record bosses in Nashville were finally raking in enough coin to hang out in New York and L.A., and "crossover" was the buzzword of the moment. That's why Jimmy Buffett, Anne Murray, and Kenny Rogers were on the Urban Cowboy soundtrack along with Lee, Gilley, Bonnie Raitt, and the Charlie Daniels Band, who were filmed playing at the club. The entire lot ended up at Number One on the charts.

On his contributions, Gilley patterned his performances after his cousin Jerry Lee Lewis, but he was also strong as a crooner in the mold of Charlie Rich and Ronnie Milsap, the style that first brought him to prominence on "Roses." When Travolta is trying to make Winger jealous, the song he and Madolyn Smith dance to is Gilley's rendition of "Stand By Me." The real hardcore country fan was Cryer.

"I brought the country music in, and [Gilley] always made fun of me," says Cryer. "I brought in Kitty Wells, Faron Young, Ferlin Husky, all of that bunch -- Hank Snow. Gilley didn't like that, because he thought that was degrading that I would bring in those country & western acts when he wasn't playing country. Hell, he was playing pop-rock."

"I'd run the entertainment part and he'd run the nightclub," counters Gilley. "Instead of him letting me help him with the entertainment end of it, I was trying to tell him, you know, who he should book in there and who he shouldn't, and he didn't like that."

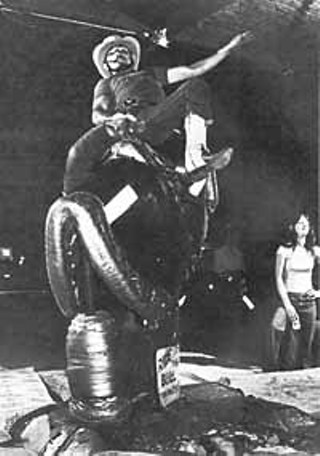

Whether it was Merle Haggard, Lee Greenwood, or Roy Orbison, chances are the tapes were whirring away in the adjoining recording studio. Chances are even better, however, that a lot of paying customers missed the music altogether, watching instead some young pipefitter getting his meat tenderized on the club's mechanical bull.

El Toro

"The first time I rode the bull, I never thought I'd be able to have kids," remembers Lee, today the proud father of a nine-year-old son.

"That son of a bitch was an instant success," is how Cryer puts it. "It was more popular than the entertainers that we brought in."

That was certainly Latham's point of view, as his Esquire article followed the exploits of Dew Westbrook, mechanical bull rider, in much finer detail than those of Mickey Gilley.

"All the time, [Latham] was interested in the bull, and the people that gathered around the bull, and the people that came into the place nightly," says Cryer. "The article came out, and I think Gilley made fun of it, but I told him, I said, "Hey, you don't need to make fun of that article. That ol' boy has wrote a good story about us.'"

The truth was, the bull was becoming as synonymous with Gilley's as Mickey was.

"I didn't like it either," admits Gilley. "There was too much noise going on. It was off on one side, but you could hear it because they had that cowbell thing on it and it would ring. You could hear 'em ridin' it."

None of the performers were too thrilled about it.

"They demanded I cut that son of a bitch off," says Cryer, "but we had it about 100 yards from the damn bandstand. We finally put three bulls in out there, and they ran continuously. A bunch of them entertainers raised hell because they wanted the bull shut down, but they never put it in their contracts. I think Johnny Cash did, but I just rubbed that out because, hell, that bull was popular!"

Others weren't quite as distracted.

"Gilley never did like the bull going when he was singing," recalls Lee. "I didn't care. The only time it bugged me was when you were trying to sing something serious and you'd hear all them sirens going off on the punching bags and all that."

As long as they weren't competing with the plethora of amusements for patrons' attention, some entertainers even wanted in on the action.

"Every time on the breaks, that's what I'd do, man," admits Lee. "I'd punch the punching bag with the best of 'em and I'd ride the bull."

Others didn't get as much practice.

"Mel Tillis came out there and rode the bull, and that bull tore his damn britches off," Cryer says with a chuckle. "He had to change his ol' britches, so we hung them up there and said, "This belongs to Mel.'"

The bull had a star quality of its own that seemed custom-made for the silver screen. In "Time-Traveling Through Texas: A Half-Century of Lone Star Movies on Video," the epilogue of his 1998 book Giant Country, author and UT English professor Don Graham agrees.

"There is not one good or authentic country & western song in the entire movie, but there's still Debra Winger riding the mechanical bull like it was meant to be rode, and that's enough."

Cryer spotted El Toro's potential early on.

"When I read the script for the damn movie, I said, "Hell, the star of this movie is gonna be that damn bull,'" says Cryer. "The ol' boy that owned the patent for that bull [Joe Turner], he lived out in Corrales, New Mexico. He wasn't making any money with it. Joe told me, "I'll sell you the whole shit and caboodle for $30,000.'

"So I called him up after I read the script and said, "Joe, I think I'll buy that patent off of you for the bull.' He said, "Well I see Paramount's fixin' to do a movie down there. My price has gone up a little bit.' I said, "OK, I'll come out there and talk to you.'"

One hundred thousand dollars lighter, Cryer walked away with rights to manufacture and distribute the metallic beasts, which didn't exactly draw the most genteel crowd. Most of the time, whoever was working the bucking controls took special delight in knocking riders on their ass. Emotions, adrenaline, and blood-alcohol levels all ran high, leading to some heated exchanges. But not everyone showed up looking for trouble.

"The tourists didn't fight," explains Cryer. "It was them rednecks that was working in all these plants around here, come out there to roar and let off steam. We very seldom put a tourist in jail at all. We put in several of them rednecks -- had to. They didn't want to go on after we threw 'em out."

Cryer laid down some very simple rules concerning such outbursts.

"If he was fightin', we just threw his ass out, told him not to come back," he says. "If he gave the police a lot of trouble, well, they would haul him in. But I didn't want them taking all them damn people to jail. They were out there just livin' it up. I told 'em, "If you got a man that's fightin' in the place, throw his ass out.' Tell 'em to go on home and come back tomorrow night. So hell, they'd come back with black eyes, skint-up noses. They probably didn't remember it the next night."

In Urban Cowboy, the K.O. punching bag is installed "to give the cowboys something to beat on besides each other." At Gilley's, the fisticuffs were usually more sport than hostility, but not always.

"It used to be really wild," says Lee. "I remember one time the biggest cop on the Pasadena police force went back up in there to break up a fight, and he got the shit beat out of him. They stole his gun."

Mostly, according Lee, they were just "good ol' rednecks."

After the Show

"We opened up Gilley's in 1971, [and] it was halfway decent," Gilley recalls. "It was a little bit better than a joint, but as time moved on, after we did the film, it turned into a joint."

Among the improvements Gilley suggested was carpeting the floor, but Cryer points out that all those Skoal-dipping cowboys would have done in such improvements quicker than the time it took to hose down the club's concrete floors. Nevertheless, in Gilley's mind, there was a lot more wrong with the club than a morass of expectorated snuff on the way to the stage.

"It was filthy," he says. "When it rained, there was water in there. When it got cold, it was cold in there. When it got hot, it was hot in there. [Cryer] made the club bigger, but he didn't make it better."

Gilley also took exception to Cryer's charging Conway Twitty prices to people who knew him since before "Room Full of Roses."

"It was ridiculous to charge $20 at the door to see Mickey Gilley," complains the singer. "Or $15, $10 -- whatever -- when they used to get in for $5 when I was playing up and down the Spencer Highway. Why go back and rap the people a big hard one for me coming in and playing on a Friday or Saturday night? It didn't make sense to me. He was just greedy. I wasn't costing him anything. I was bringing the band in and playing; I wasn't getting my fee like when I'd go on the road with Conway."

Cryer maintains that the times he could get those kind of prices were becoming scarce.

"When that slump hit us in the Eighties, Gilley was making more money than the club was making, but he decided he didn't want to give me my half to keep the club going, so we got crossways."

The lawsuit followed not long after, and things became even less savory.

"[Cryer] took a contract that was a 10-year contract and presented it to the court with 11 years on it, and he wouldn't produce the original," claims Gilley. "The judge ordered him to produce the original. He said, "This contract has been doctored.' My lawyer said, "Your honor, I want 48 hours to examine this document. I want to see the original document.' And Mr. Cryer would not produce it."

"He convinced the damn jury that I was the boogerman in the deal," rebuffs Cryer, "and they took everything I had. I didn't have a pot to piss in or a window to throw it out whenever Gilley and his slick-tongued lawyers turned me loose."

Gilley got the name, the nightclub, recording studio, and assorted properties in Pasadena and Nashville, while Cryer maintained control of his pre-Gilley's establishments in exchange for dropping his appeal of the verdict. "This means it is all over," Gilley attorney Tom Alexander told the Houston Post in September 1990. By this time, Gilley was a regular performer in Branson, Missouri, and still is ("I'm putting about 950 people in the auditorium every time I walk out on stage"). The singer also runs a couple of restaurants in Branson and Myrtle Beach, where customers can sample "Gilley's Hot Sauce" and "Gilley's Wild Bull Chili," and has a piece of the action from the Gilley's store in Vegas' Frontier casino.

"I'm in control with this theatre and my restaurants, and I don't let anybody tell me how to run 'em," says the 63-year-old Gilley. "I was ready to settle in one place. I got a nice theatre here, and I can sleep in the same bed every night, and I can walk right out and do my shows on the stage."

After every show, Gilley stands at the back signing autographs, just like he did on Spencer Highway. He says about 10% of the signature-seekers talk about the old Pasadena days. Others plug in through his Web site, http:// www.mickeygilley.com. Johnny Lee has relocated to Branson as well, and is raising his son while waiting for the "right deal to come along." He says he'd love to be a part of an Urban Cowboy reunion tour.

"It would pack coliseums and stuff," he says. "I had an idea to do that a couple of years ago, but nobody's really ever moved on it, and I don't have the stroke to get it going. I think some beer companies or Coca-Cola or Pepsi or whoever -- Budweiser with the commercials they do, or Miller Lite. I think they'd jump all over it."

Closing Time

Deer Park is an industrial, second-ring suburb sandwiched between Pasadena and Baytown. The only deer left play for Deer Park High School. Yankee southpaw Andy Pettite is an alumnus. If you come down Texas 225 from Loop 610 or Beltway 8, you'll see the very Blade Runner-esque Shell plant, which looks like something we bombed in the Gulf War. Right past the plant, you'll see G's Ice House, which looks like it hasn't changed a lick since before most of that oil was still in the ground. It's not hard to imagine why; a sign off the access road advertises upcoming shows by David Allan Coe and Hank Williams III.

Sherwood Cryer, now 74, is sitting inside, surrounded by vending-machine paperwork. His son is out back in the mechanical bull shop, sauntering and lathing another El Toro model destined for somewhere far away. A crate in the parking lot is destined for Oregon, and Cryer says a goodly number of his orders come from Latin America (other comments about Pasadena's own Spanish-speaking population make Wes Hightower sound like Henry Cisneros).

"I'm trying to make a comeback, but how does an old man make a comeback with nothin?" he wonders. "We do whatever we can to make a livin'."

He's happy to give me a copy of Saturday Night at Gilley's, and autographs it, "From the man that put Pasadena, Texas, on the map, kept all the drunks drunker, and enjoyed every minute." Cryer says G's is having an Urban Cowboy reunion November 13, and he expects to see some old faces, whom he says stop by once in a while to shake his hand and reminisce. He throws in a ride on the mechanical bull, and for a couple of hours afterward, I, too, question my reproductive future.

Gilley's will never fade from memory for thousands of Pasadenans and Houstonians, but neither has it completely vanished physically. The property at 4500 Spencer Highway still belongs to the Pasadena Independent School District, awaiting someone willing to shell out for the hefty back tax bill. A concrete slab, scattered parking lot lights, and the huge, hangar-like shell of the rodeo arena are all that remain of the world's largest honky-tonk. The sign that pointed a million pickups into the unpaved parking area is now a few miles down Spencer at the Cowboy Ranch restaurant. Folks still looking for love now have found other places to look.

"It was where all the girls went, and where all the girls went, all the guys came," says Johnny Lee, who grew up in Texas City and, like Gilley, makes frequent trips to the area. "Nobody ever got killed there, nobody ever got stabbed there."

He pauses as a memory surfaces.

"Yeah, my bass player did. His ex-wife stabbed him with a beer bottle. She thought he was going out with somebody one time, but that was in the early days."

So one question remains. The man to answer is Dale Watson, who attended South Houston High School and "almost got in three fights before 10pm" when, at all of 14, he saw Willie Nelson live at Gilley's. So, Dale, did the girls really all get prettier at closing time?

"No, it was Pasadena." ![]()