Love in the Time of 'Green Darkness'

Don't judge Anya Seton's reissued biofics by their romance and bad covers

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Sept. 29, 2006

Elegantly mannered and exhaustively researched, the writing of Anya Seton has captivated readers for decades. Books such as Katherine, Green Darkness, Avalon, and Devil Water have remained continuously in print for nearly 70 years, a remarkable tribute to her storytelling allure.

Seton published her first book, My Theodosia, in 1941. The compact story of Aaron Burr's daughter, her marriage to future South Carolina Gov. Joseph Alston, and her love for explorer Meriwether Lewis, combined with her mysterious death was a bestseller. In 1941, America was also coming out of the shadow of the Depression and gripped by prewar jitters, fueled by the sentiment that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt encouraged the country into combat for economic reasons.

It was a profitable era for female authors. Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind, Pearl S. Buck's The Good Earth, Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca, and Kathleen Winsor's Forever Amber rang up cash registers at the theatres as well as bookshops. Those books also whetted the public appetite for historical themes, exotic locations, romantic mystery, and compelling heroines. Enter Anya Seton.

She was born Ann Seton in New York City in 1904, the only child of Boy Scouts of America founder and naturalist-conservationist-illustrator Ernest Thompson Seton and writer Grace Gallatin. Ernest Seton was a British subject, descended from a long line of notables in Northumberland near the Scottish border. He maintained that sense of heritage when he immigrated to America and amassed his fortune.

Grace Gallatin was no less active, a founder of the Campfire Girls who organized a French relief effort during World War I and twice president of the National League of American Pen Women. She also authored seven travel books and served as president of the Connecticut Women's Suffrage League.

Despite her family wealth and innate intelligence, Anya Seton did not attend college. Married at age 19 to Rhodes scholar Hamilton Cottier, she bore two children and divorced him within five years. In 1930, she married Hamilton Chase, an investment counselor, and had one daughter with him. Her parents divorced in 1934, and her father relocated to New Mexico, a setting that inspired two of her books. Seton's name is sometimes credited as "Anya Seton Chase," but they divorced in 1968.

The success of My Theodosia was followed by the equally successful Dragonwyck in 1944. Seton's next novel, The Turquoise (1946), took place in the American Southwest, then she moved settings to Marblehead, Mass., for The Hearth and the Eagle (1948). She returned to the Southwest for Foxfire in 1950, the fifth of her 10 bestsellers. Dragonwyck and Foxfire were made into popular films of the day, starring Vincent Price with Gene Tierney and Jeff Chandler with Jane Russell, respectively.

In 1954, Katherine was published. It told the tale of Katherine de Roet Swynford, the 14th century English-born beauty who was first mistress to then-wed John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster, and bred the Plantagenets, Tudors, and Stuarts. The first of Seton's intensely period novels, Katherine is a glorious example of romance in its most classic literary sense: exhilarating, exuberant, and rich with the jeweled tones of England in the 1300s.

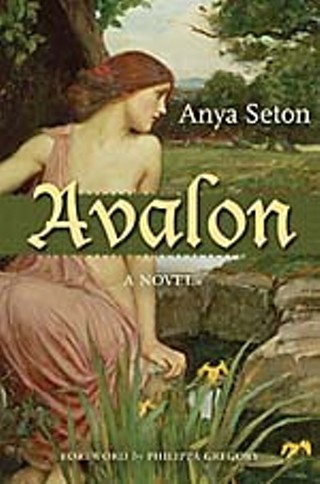

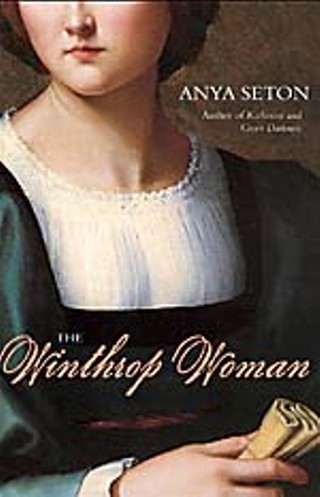

The next three books further delved into Seton's fine sense of history. The Winthrop Woman (1958) crossed from Puritan England to Colonial America. Devil Water (1962) likewise traveled from Jacobite Scotland to the colonies, while Avalon (1965) sailed from Cornwall to Iceland and North America in the late Dark Ages.

The Underground Railroad, the Viking raids on England, the Jacobite Rebellion, the rise of Protestantism, the Acadian diaspora, and the Colonial Puritanism: These events bloom vividly in the reader's imagination because of Seton's eye for accuracy. Who else would take the horrific discovery of a girl walled up alive in an English castle and recast it as a tragic time-travel romance between a monk and a noble's bastard daughter?

Anya Seton did, and, in 1972, Green Darkness became her most popular novel by far, spending six months on The New York Times bestseller list. It wasn't simply Seton's deft touch with historical facts woven into the tale of forbidden love; she added an element of reincarnation that made it even more irresistible to the denizens of the dawning of the Age of Aquarius. It was the last of her full-length novels, for ill health set in a few years later.

Seton had a remarkable ability to bring famous and not-so-famous characters to life in the background and forefront of her stories, often replicating the cruelty and harshness of those times without prejudice. Colonial heretic Anne Hutchison (The Winthrop Woman), the hapless King Edward (Avalon), a drug-addicted Edgar Allan Poe (Dragonwyck), and charming Geoffrey Chaucer (Katherine) appear in her books without ever upstaging the principles.

Her literary themes are enduring: strong, courageous female protagonists whose hearts lead them astray or have societal demands placed on them before coming into their own. Neither did they assume traditional happy endings. Though she called her works "biographical novels," she was regularly cited among historical romance readers and novelists as being the best of the breed. This did not please her.

"There is a difference," she wrote, defending her distinction. "The standard costume piece or historical romance needs very little research. It is sufficient to pick a congenial period, then read a couple of books in order to properly clothe and feed the characters, who are invented by the author. And since love and conflict are common to all ages, the historical background can be negligible. My own works are very, very different in approach. I have a passion for facts, for dates, for places. I love to recreate the past and to do so with all the accuracy possible. This means an enormous amount of research, which is no hardship because I love it."

In the glory days of paperbacks, book covers were benign settings that vaguely suggested the story's elements. Romance books often fared badly, with the publisher's art department rendering redheaded heroines as sultry brunettes. As pulp fiction grew popular in the Fifties and into the Sixties, many of Seton's books received the same negligent treatment.

A particularly lurid cover for a mid-Sixties Cardinal paperback edition of Devil Water depicted an upside down crucifix and hooded priests circling a blonde cowering on the ground. Above her, a man brandishes a human skull. A Pocket Books printing of Foxfire depicted a dark-haired beauty in a form-fitting serape that suspiciously resembled Jane Russell, star of the film, with suggestive details that had little to do with the book.

Disappointingly, this sort of sloppy interpretive artistry is the case with Chicago Review Press' recent line of reissued Anya Seton novels. The notion of using classical art could only enhance Seton's timeless stories, yet artistic carelessness abounds. Katherine's Katherine de Roet is given prim pre-Raphaelite treatment, and Avalon's Merewyn is portrayed by a Waterhouse myth, both in a style created more than four centuries after their lives. Green Darkness fares only somewhat better with the teenage, golden-haired Cecilia de Bohun from the early 16th century recast as a well-fed, chubby-cheeked ash blonde straight from Marie Antoinette's retinue.

Worse, the fey blondeness of Dragonwyck's Miranda Wells is tampered by the cover of a lovely dark-eyed brunette gazing coquettishly from over her milk-white shoulder. Only the most recent of the Chicago Review titles, The Winthrop Woman, seems to get it right, even if the garb is inaccurate for Elizabeth Winthrop's Puritan times. If this seems quibbling, consider how it would have looked to illustrate Scarlett O'Hara as a blue-eyed redhead in an empire-waist gown.

The reprinting of these books, however, is a reminder that a compelling plot and sympathetic characters survive through time and fickle publishing trends. Anya Seton's meticulous prose eschews the florid styling of today's romance writers, but she did not shy away from topics such as homosexuality, drug addiction, adultery, pedophilia, and rape. These may be grist for talk shows today, but they were brave subjects to tackle in the Forties and Fifties. New introductions in the Chicago Review series by authors such as Philippa Gregory give Seton's writing a contemporary context.

Besides the recent reissues, she wrote three young-adult books: a biography of Washington Irving and two historicals, The Mistletoe and the Sword (1956) and Smouldering Fires (1975), the least effective of her works. The basic premise of the past visiting itself on the present so beautifully created in Green Darkness is shapeless and unsatisfying in this abbreviated novel that comes across like Green Darkness Lite. Smouldering Fires was her final work.

Perhaps that was just as well, for the changing standards in Seventies book publishing left her beautifully crafted writing behind: It was the burgeoning age of the bodice-ripper romance. Seton had become synonymous with those romance writers. Her historical fiction deserved better to be placed on par with Dorothy Dunnett and Mary Renault, yet her marvelously protracted embrace of love kept her shelved among heaving bosoms and lantern-jawed rogues.

Because of that association with romance readers and writers, Seton rarely received the literary respect she was due. Nonetheless, she influenced an enormous number of contemporary authors, such as Sharon K. Penman and Diana Gabaldon. Anya Seton died in 1990, yet her books remain well-loved and well-read decades after they were written. There is no doubt that she's the grande dame of historical romance. Er, biographical novels. ![]()