Book Review: Readings

Stanley Elkin

Reviewed by Caroline Kim, Fri., Feb. 23, 2001

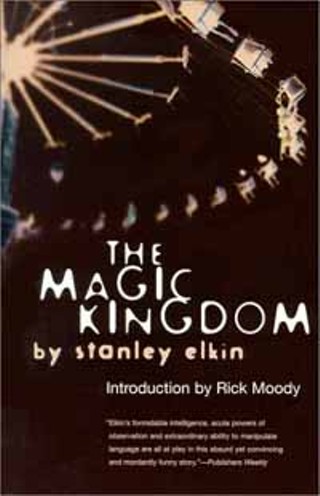

The Magic Kingdom

by Stanley Elkin

Dalkey Archive Press, 317 pp., $12.95 (paper)

The premise of The Magic Kingdom sounds like a three-hankie weepie begging a maudlin soundtrack: Seven terminally ill children are flown from London to Disney World on a "last hurrah" dream vacation. Will you believe that it's actually quite funny? In other, less brilliant hands, we might find ourselves in Cheese Valley, but one never runs that risk with Stanley Elkin.

The idea for a "last hurrah" vacation belongs to Eddy Bale, who himself knows something about terminal illness, having lost his 12-year-old son, Liam, to leukemia. In the four years that Liam is sick, and in order to raise the £100,000 to keep him alive, Eddy and his wife, Ginny, literally go door to door raising funds, even resorting to selling their grief to the tabloids for payment. By the time Liam dies, Eddy is a "public griever," adept at squeezing into the boardrooms of Rothschild's and British Petroleum, Guinness and the British Rail, among many others. He even manages to squeeze a few pounds from the Queen (a revelatory scene, take my word for it). There's a great irony, of course, when a dying child visits Disney World -- the utter reality of terminal illness colliding with the clean, efficient unreality of a groomed cartoon world. Treated as a giant stage set, its employees called "cast members," even the name Magic Kingdom -- it all sounds like something conjured up by someone on drugs. And when the kids see other groups of children like themselves -- thin, sick, missing limbs, distended, distorted, from South America, Asia, Africa -- they grow queasy, recognizing that they themselves are on show in the same way. That, perhaps, is the point of The Magic Kingdom, which was published in 1985 and recently reissued. "The old triumph-of-the-human-spirit bit," Elkin writes. "Folks showing their lesions and cancers, exposing their stumps, sniffing their gangrene. There really was no business like show business."

There's something vaudevillian about Elkin's voice, a barkiness that reminds me of preachers or used car salesmen or those late-night commercials for Crazy Eddie's. His language runs at a higher rpm, lush, abundant, spreading like a fever. He calls out the dazzling descriptions of diseases like a circus barker calling out the activity in an emergency room. And these are kids with some serious diseases (you know them by their serious names: osteosarcoma, cystic fibrosis, ventricular septal defect, progeria). These are children who also look and smell different, act different, are different. They're the only kids their age faced with their own mortality. And Elkin doesn't cut them any slack. Or us either. Which is just the thing that makes the novel work.