Manufacturing Innovation

Is the next big thing a product of inspiration, perspiration, or just dumb luck?

By Nora Ankrum, Fri., March 13, 2015

Among the panels at this year's SXSW Interactive, there are roughly 40 with some iteration of the word "innovation" in the title and no doubt countless more that will address the topic in some way. Matt McFarland, editor of the Innovations section of The Washington Post, laughed when he learned that his panel – Innovation, Meet Regulation – would be joining a crowded field. "Everybody wants to be innovative," he said. "It's such a buzzword that it's losing a lot of meaning." Asked what the word means to him, McFarland was quick with an answer. "It's a creation that adds value to the world," he said. "It's something that hasn't been done before. It's new, it's different, and it's useful."

McFarland's answer was remarkably similar to that of MIT Leadership Center Executive Director Hal Gregersen, co-author of The Innovator's DNA (and host of a panel by the same name). When asked the same question, Gregersen replied, "It's a new idea that generates value. The value could be financial, could be social, could be emotional – but there's something valuable that's come from that new idea."

This focus on value is interesting considering that so many good ideas, including some of history's most celebrated inventions, start out utterly useless. The classic example is the Post-It note, the Red-Nosed Reindeer of office supplies. As the story goes, a failed experimental adhesive languished in a 3M lab for years, exhibiting no fathomable purpose until its fortuitous pairing with a piece of yellow scrap paper. As similar origin stories of countless inventions attest, the best ideas tend to be the most unexpected. Consider Wilson Greatbatch, who accidentally invented the pacemaker, or Charles Goodyear, who accidentally invented vulcanized rubber, which later became the tire.

Serendipity is the holy grail in the quest for innovation. It is the essential ingredient not just in mankind's greatest inventions but in the greatest invention, life itself, beginning with that spontaneous combination of unwitting molecules that produced the first single-celled organism. Theorists who study innovation are in fact pursuing the oldest mystery of the universe, the genesis of creation itself. It's a riddle that can't be solved. Nonetheless, in the age of big data, it's a riddle that can at least be approximated. Even though no one knows exactly when, where, or how an innovation will emerge, McFarland, Gregersen, and others have learned a lot about the conditions under which it is most probable.

For their book The Innovator's DNA: Mastering the Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators, Jeff Dyer, Clayton Christensen, and Gregersen interviewed innovative thinkers in companies all around the world. The project – still ongoing – now has a database of nearly 12,000 people from more than 100 countries. "The results are consistent," says Gregersen. The people most likely "to get new ideas that are valuable – new businesses, new products, new services, new processes that actually create a financial value" – are those who are most inquisitive. According to the data, innovative leaders spend twice as much time asking questions as their non-innovative counterparts, and that time accumulates significantly. "You get to be in your mid-50s, that means you've spent 18 years doing this stuff, and non-innovative leaders have spent nine years," says Gregersen. "What it translates into is the innovators actually have more data points to draw on when they're trying to get an idea of value."

Gregersen leads "catalytic questioning" exercises with groups large and small in which participants spend about 20 minutes brainstorming 75 to 100 questions about a perplexing problem they hope to solve. "We're not going to give answers, because that's the knee-jerk leadership response," he tells them. "We're not going to explain why we're asking the question, because our explanations often contain our answers that we already have." These sessions have proven so successful in helping people discover new insights into stubborn problems that Gregersen now practices a miniature version of the exercise himself. He sets aside four minutes each day (accumulating 24 hours a year) to write out questions regarding whatever dilemma he's facing. "Asking nothing but questions on average suspends our convictions about the issue," says Gregersen. "We have a belief structure that says, 'This is the way it is,' and asking those questions ... allows us to start seeing things differently."

Having written biographies of some of the greatest minds in American history – Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, and Steve Jobs – Aspen Institute President and CEO Walter Isaacson knows a lot about people who see things differently. Or, as Jobs would say, they "think different," says Isaacson. Having conducted more than 40 interviews with Jobs over the course of two years, Isaacson found that Jobs' proudest achievements weren't products like the iPod or the Macintosh. Instead, he was most proud of his team at Apple. "Being able to create a company that can continually be innovative was the most important thing he produced," says Isaacson.

With his most recent book, The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution, Isaacson takes a closer look at how teams innovate – a move away from the typical biographer's approach. "We make it seem like it's a lone guy or gal in the garret or garage, then a lightbulb moment, and creativity happens," says Isaacson. "I wanted to get back to that notion of a group portrait of creativity." He and fellow panelists plan to further explore the role of collaboration in their panel How Innovation Happens. Isaacson says that teams expose people to ideas unlike their own, facilitating those "imaginative leaps that come from not being stuck in one silo – from being able to understand the connections, for example, of art to technology." Even great visionaries need a great team, says Isaacson. One of history's most creative minds was Leonardo da Vinci, because he could connect art, science, the humanities, and technology in unexpected ways. And where did he start out? In a team. "Art was not a loner's endeavor when Leonardo was young," says Isaacson. "He worked in a studio that may have had 20, 30 young artists and one or two great masters producing products and projects."

According to both Gregersen and Isaacson, an innovator's environment is important. Gregerson likes to ask people, "Physically, where are you when you get your best ideas?" Answers run the gamut: in bed, on a bicycle, in the shower. "If you want to get a new idea," says Gregersen, "What do you have to do? You take more showers, if that's your place." By contrast, people who work in teams typically draw a blank when he asks where, physically, their teams get their best ideas: "They have no idea, because they don't go there." He got a different response from the CEO of Cirque du Soleil, who told Gregersen: "Go to the cafeteria. That's where groups get great ideas here." In that space, performers come together with administration and others from all aspects of the business. "You get all these conversations," says Gregersen, "and it's just like a beehive." Jobs had a similar idea in mind when he designed the headquarters for Pixar and Apple. He "tried to make big, open common spaces where serendipity would occur," says Isaacson.

The cafeteria principle applies also to cities, where quantity, density, and diversity of talent and ideas come together like nowhere else to drive innovation and growth. In 1890 Alfred Marshall, one of the founding fathers of modern economics, took an almost mystical approach to describing what happens in centers of industry: "The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries, but are as it were in the air, and children learn many of them unconsciously. ... If one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus it becomes the source of further new ideas."

There is certainly something special in the air in Austin, the last U.S. city to succumb to the Great Recession and the first to recover, says Michele Skelding, senior vice president of Global Technology & Innovation for the Greater Austin Chamber of Commerce. "Most of the rest of the nation isn't experiencing this kind of job growth," she says. "We're sort of a shining star right now." Skelding and other local innovation experts will decode that special something in their panel Designing Austin's Economy – An Innovation Uproar? Research on the magic behind Austin's Eighties transformation into Silicon Hills has long pointed to the intersection of business, government, and academia. Today, the chamber helps nurture those connections through meaningful events and social media tools that bring everyone together. "When you're a start-up, it's just you," says Skelding. "So actually creating spaces where you work, creating the opportunity to engage with investors, mentors, and how you go about building that business is one of the most important elements of actually fostering innovation."

Although government can facilitate innovation, it can also hinder it. McFarland has learned this lesson in his coverage of disruptive technologies and business models (e.g., drones, Uber, Airbnb) for The Washington Post. "We kind of all have our eye out for cases when regulation isn't actually helping the average citizen, when it's almost protecting the established industry," he says. In their panel discussion, he and fellow D.C. cohorts will explore these cases, along with solutions (even the government can innovate), with an eye on the national regulatory environment.

Like any conference, Interactive itself operates much like an innovation ecosystem in miniature – albeit, on steroids. Innovation is both the driving force behind everything the Fest celebrates and the outcome it pledges to deliver. As "an incubator of cutting-edge technologies and digital creativity," the event promises not just to showcase the most original products and ideas but to be that primordial soup from which the next big innovation will emerge. No one in search of that aha moment knows exactly where or when the elements will combine just right (although everyone seems to agree that standing in line for coffee is a good bet). But anyone who shows up is privy to that special something "in the air," and that's not a bad start.

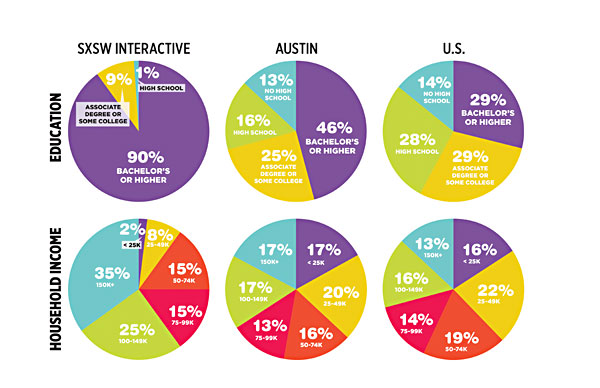

Innovation Singularity

We compare the demographics of the U.S., Austin, and SXSW Interactive. Does education and income equal innovation?

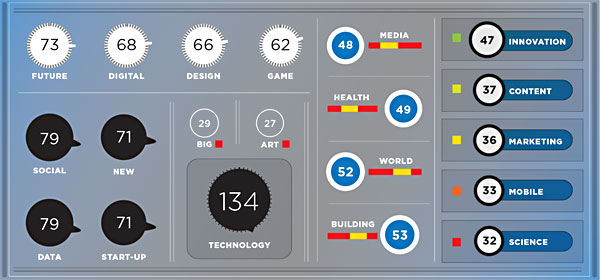

Turn it up

Here are the most common words in the names of SXSW Interactive panels. (Numbers=frequency out of roughly 2,900 unique words)

Related Panels

Designing Austin's Economy – An Innovation Uproar?

Sunday, March 15, 11am

Hilton Austin Downtown, Room 400-402

How Innovation Happens

Monday, March 16, 12:30pm

Austin Convention Center, Exhibit Hall 5

Innovation, Meet Regulation: A Tri-Sector Approach

Tuesday, March 17, 12:30pm

Hilton Austin Downtown, Salon K

The Innovator's DNA: The Five Innovation Skills

Tuesday, March 17, 12:30pm

Hilton Austin Downtown, Salon D