Brand on the Run

Synergy is the name of the game at Drafthouse Films, the distribution arm of the Alamo empire

By Richard Whittaker, Fri., Aug. 31, 2012

Tim League is sitting at the bar, at his bar, the HighBall. Next door at his cinema, the Alamo Drafthouse South Lamar, the audience is wrapping up a Q&A with the stars of Klown, the latest release from his fledgling Drafthouse Films. The next day, he will be sending reviewers on a canoe trip down the Guadalupe River for a one-of-a-kind outdoor screening of the filthy-dirty Dutch comedy. But League is already thinking about his next film. He just secured libel insurance for The Ambassador, a controversial new documentary shot in the blood diamond mines of central Africa. Is it risky? Absolutely. But that's why he founded his own distribution company in the first place. He calls Drafthouse Films "a space for us to champion things that we love, because a lot of things we love are a little bit, ah, problematic."

That's putting it delicately. For every eye-opening exercise in cinema verité like The Ambassador, there's an underground oddity like Eighties throwback The FP or a rediscovered classic like Australian ocker-shocker Wake in Fright. So what makes a "Drafthouse" film? "I don't know if we've made a hell of a lot of decisions based on commercial viability at this point," says League. "I'll either just watch it, and immediately fall in love with it, or I'll watch it and I can't get it out of my brain. It either has to do with people being really bold, or being fresh and original and really awesome."

If there's one thing that's undeniably true about League, it's this: When he loves a film, he really loves it and will do anything to support it. That's why Drafthouse Films began with Four Lions, the pitch-black British comedy about bungling wannabe jihadists. As League notes, "I saw Four Lions at Sundance as an absolute megafan of [director] Chris Morris, and then watched it just sit on the vine for six months." It was the kind of film that everyone adored, but no one knew how to distribute. So in September 2010 he ann-ounced that the newly formed Drafthouse Films would be co-releasing it with Magnolia Pictures. So, was it a well-considered evolution and expansion of the Alamo Drafthouse brand, or did League just get up one morning and think, fuck it, I'm going into film distribution. "It honestly was more of the 'fuck it' variety," he admits.

Fortunately, League knows people like Tom Quinn, the former head of acquisitions at Magnolia Pictures, now co-president at Weinstein Co. boutique Radius-TWC. A regular at the Drafthouse's own Fantastic Fest since 2007, Quinn worked with League before on crafting campaigns for oddities like FF fave Timecrimes. For online promotion, League turned to the Alamo's go-to publicity firm, Fons PR. Then he dropped the big news. Most films get a three-month publicity campaign. But, as Brandy Fons recalls, "We had a month to do it in." They launched a screening tour with Morris, and put a special push on for reviewers. The payoff was that the company's first release made it onto many critics' year-end lists, even getting a fingertip into Time's top 10 of 2010.

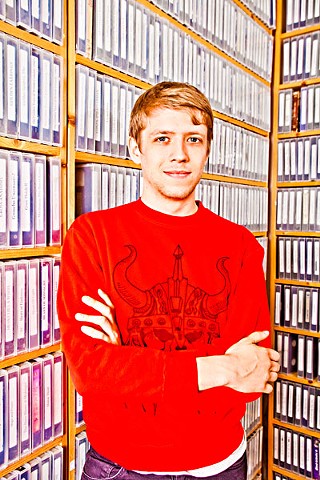

Even League was unsure if this was a one-off adventure, but the critical and commercial success of Four Lions left him "comfortable-ish about how this works." Now he needed his own team of seasoned pros, so he would not have to constantly rely on partner firms like Magnet Releasing. First, he hired as president Evan Husney, a fervent metalhead and gorehound from underground doyens Severin Films. Then James Shapiro, former acquisitions head for Anchor Bay, came on board as chief operating officer. Both knew the grimy side of film distribution: Husney used to stack boxes at Troma, while Shapiro was a buyer for Hollywood Video. Like Quinn, they knew League from Fantastic Fest, and both had worked with him before. League was blown away by how Husney turned the seemingly unreleasable Birdemic into a legitimate underground success – in no small part through special screenings at supportive cinemas like the Alamo. "I was one of seven people that got a chance to see that film at this guy's private screening, projected on a wall at Sundance," he says.

When League announced the Four Lions deal, Husney recalls thinking, "'This totally makes sense for him as the next logical step for the company.'" At the time, Husney was dealing mostly with repertory films and was looking to deal in new releases. When he got the call from League to come join the team, Husney was "completely floored" – and eager to sign on.

One of Husney's first tasks was to take the idea of Drafthouse Films and turn it into a real company. Image Entertainment came on as a video-on-demand and Blu-ray partner. The slate expanded with all manner of what Husney calls "the artfully unusual, visceral, and original," including the restored 3-D spaghetti Western Comin' At Ya! and Electric Boogaloo, the documentary history of the equally gonzo and eclectic Cannon Films. Even if Four Lions had been a wild experiment, that first release forecast Drafthouse Films' modus operandi. Difficult topic? Check. Off-the-radar creators? Check. Critically adored? Check. Impossible to get into a multiplex? Check. Foreign? Check. And only a month to launch? Double check.

That sounds like an impossible job, but it's standard operating procedure now. For League, that means "when we're working on a movie, we're working on – a – movie." That's a schedule that they hope fans will mark on their calendar: In June, the company launched the Drafthouse Alliance – basically a DVD club where members could preorder the next nine releases. It's a restrictive slate, and now League's personal faves have to justify a slot against Husney and Shapiro's selections. Yet, for a firm specializing in off-the-beaten-path projects, it's a lot easier when there are three movie obsessives scouring the festival circuit for that next passion project. Says Husney, "We're curating our brand like we would our own DVD shelves."

From the PR point of view, that month leading up to a release is spent reaching out to the right reporters and finding the right tools in the Alamo toolbox to promote each film just so. Buzzword time: synergy. For Fons, it was about bringing "the Drafthouse touches" to a release. Say Drafthouse Films picks up a movie that no distributor in its right mind would touch. The Alamo's in-house news site Badass Digest can talk about it; print maestros Mondo can release a limited-run poster (or underpants, as was the case with Klown); Rolling Roadshow hosts a special screening; and, unlike most small distributors, League and Co. know they can book screens. That's the big advantage of owning your own cinema chain. "Breaking through those barriers by attaching the Alamo brand and Fantastic Fest and using those efforts to break that mold and get coverage has been challenging and rewarding at the same time," says Fons.

If Four Lions was an auspicious debut, then the real turning point was Bullhead. As their second release, League and company snuck out The FP to bemused shrugs from many critics, but Bullhead, a steroid gangster drama, was on a new level. This was Belgium's Oscar-eligible feature, so, you know, no pressure there. "The movie's strong," League explains. "It's an arthouse movie with some real hard-to-watch moments, so I think it stuck it in this limbo-land where traditional buyers, despite the good reviews, went, 'Nah, I don't see the audience for this.'" League had worked hard to convince sales agents Celluloid Dreams to schedule its U.S. debut for Fantastic Fest 2011, and off the strength of that premiere was pinning his distribution date to whether it got an Oscar nomination or not. When it made the short list, there were cheers, but also a slight sense of panic. If Four Lions' month-long push had seemed tight, this time they only had three weeks to put together an Oscar-worthy publicity campaign. "We knew that we weren't going to win," he admits. The smart money was on Iran's entry (and eventual winner) A Separation, but that didn't stop League from wagering on his own film – at 400-1 odds. "If we'd won," he says, "I would have won $4,000." Yet, it really proved there was a horribly underserved niche market. "There's really not that many buyers who are interested in foreign language anymore," says League. "It's just the nature of the industry in America, and we're dealing specifically with edgy foreign language. We've definitely got our eyes open, to see if we can do it again."

Of course, Drafthouse Films is launching at one of the most volatile times in movie history. As a theatre owner, League will always want films on the big screen. But in Shapiro's view, their future also involves "this combination between Netflix and Hulu and video-on-demand." Every smart distributor realizes that, and so everyone is playing around with new platforms. Yet Shapiro has seen it before. "At Hollywood Video, we would release 10, 12 blockbuster films a month. The secondary content, the ones that would do $10 million at the box office – or no box office [at all] – there would be 100, 150 releases every month. It became so saturated that it became difficult to make money at a certain point, and the same thing is happening on VOD," he said. The firm has already struck a deal with another Fons client, theatrical-on-demand firm Tugg (see "The Way We Watch Now," June 22), and are using online VOD/retailer firm Distrify to promote Klown. But that's part of what attracted Shapiro. He's been through the tried-and-true theatrical-rental-sale-TV distribution model with Anchor Bay, but now Drafthouse is rebuilding its model with every movie. The Ambassador already launched on VOD and kicks off a limited theatrical run in New York, Los Angeles, and Austin this weekend, whereas Wake in Fright is getting a wide repertory run. Both will also appear on Alamo screens, and Shapiro argues that's not nepotism – it's good and proven business. He cites Magnolia Pictures as a model, which has benefited from access to Mark Cuban and Todd Wagner's Landmark Theatre chain. "That has given them a big boost in terms of what they're trying to do with their VOD model," Shapiro says. "So in the possibility of trying to replicate that model or find some hybrid of it, you really do need your own theatre chain." With Alamos scheduled to open in New York, Virginia, San Francisco, and Dallas, plus extra sites in Austin and Houston, you might think League has enough to deal with, but Shapiro sees it as part of the same process. "If we're building a distribution company at the same time they're expanding all these theatres, it's an enormous advantage," he says.

For League, Drafthouse Films is "in lockstep with what we're trying to do as a movie theatre." More importantly, it's part of the bigger Alamo endeavor. And if a Mondo poster gets film press coverage, or a film gets a few extra people into Alamo seats, then so much the better. Says League, "Ultimately, we are building a brand here."