Pieces of Time

Peter Bogdanovich's latest picture show, "The Cat's Meow'

By Marjorie Baumgarten, Fri., March 1, 2002

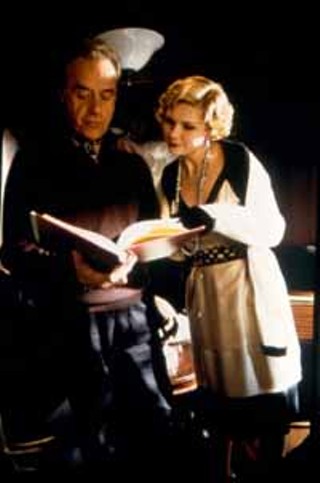

In the minds of the celebrated and well-heeled guests aboard William Randolph Hearst's private yacht during a November 1924 cruise hostessed by the media mogul's mistress Marion Davies, this particular floating party is the "Cat's Meow." But that pronouncement is made before one of the passengers returns from the two-day trip having suffered a fatal bullet wound, the other guests tight-lipped or unknowing about the events that had transpired. The true incident has passed into California lore, with sparse but conflicting reports of what had actually occurred and even who was onboard -- although some of the undisputed guests included comic hero and notorious womanizer Charlie Chaplin, pioneering producer Thomas Ince, ambitious gossip columnist Louella Parsons, and British novelist Elinor Glyn. It's a scandal that has been whispered about for decades: It's there in Kenneth Anger's Hollywood Babylon, though it was never discussed by the gossip doyenne Parsons, who curiously received a long-term contract with the Hearst corporation shortly after this incident. These are also the same kinds of characters that inform the background atmosphere of Citizen Kane, Welles' fictionalized extrapolation of the Hearst legend, along with his paramour Davies.

Who better than Peter Bogdanovich to resurrect this little-remembered Hollywood murder mystery? No stranger to scandal and controversy throughout his career, Bogdanovich has also worked various sides of the Hollywood fence. His career began at the age of 15 as an acting student in Stella Adler's famed New York workshops, an experience that also gave him the bug to direct, first in off-Broadway theatre and later in Hollywood. He came to Hollywood in the mid-1960s as a writer for Esquire, where he published a long string of industry articles and began writing several monographs based on interviews with fading American film directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Allan Dwan, and Sam Fuller. With his knowledge of and love for American movies from previous decades, Bogdanovich was regarded as one of Hollywood's bright new promises. Tutelage in the Roger Corman School of Filmmaking resulted in the tight and timely Targets (a story that conflates the stories of a Charles Whitmanesque mass murder with that of an almost-real-life Boris Karloff -- "modern horror vs. classic horror," as Bogdanovich puts it). His next three films -- The Last Picture Show (1971), What's Up, Doc? (1972), and Paper Moon (1973), with their loving tributes to genres and time periods gone by and their box-office popularity, made Bogdanovich the boy wonder of the new Hollywood.

That reputation would suffer with his next few movies -- Daisy Miller, At Long Last Love, and Nickelodeon -- which were poorly received but always ambitious and respectful of the traditions and the artifice involved in the making of movies. (On the other hand, his reputation as a film chronicler has been firmly established with such indispensable essay collections as 1973's Pieces of Time and 1997's Who the Devil Made It.) Bogdanovich's directing career would undergo ups and downs with films such as Saint Jack and Mask and They All Laughed and The Thing Called Love. At their best, these films soar on the strength of their characters and the detail of their milieus. Who can forget Cher in Mask or Tatum O'Neal in Paper Moon, the wonderful young ensemble cast in The Last Picture Show and Madeline Kahn's screen debut in Paper Moon, Boris Karloff at his most natural in Targets or Ben Gazarra at his most existential in Saint Jack?

Whether on the written page or the screen, Bogdanovich's greatest talent lies in the quality of his portraiture. His interviews with directors offer storylines as rich as those of his fictional creations. He is someone who has walked with the great ones and has studied the weight of their impressions on the sands of time. The Cat's Meow, the movie he will be presenting at the South by Southwest Film Festival, is the result of this process as well. We had the opportunity to speak with him by phone about the film.

Austin Chronicle: You're so well-recognized for your contributions to film history through your magazine and book writing and interviews with so many of the great directors active in the early decades of moviemaking. Yet I find it surprising that you've made only two films -- Nickelodeon and The Cat's Meow -- that deal directly with some of the historical aspects of film, and in both cases, silent films.

Peter Bogdanovich: Nickelodeon was really inspired by many talks with filmmakers like Allan Dwan and Leo McCarey, and I just thought the era was so interesting. The released version of the picture didn't nearly live up to anything I had in mind. Unfortunately, that's the way it went. The Cat's Meow isn't really about early film history. It's about an incident that happened during the silent era. It's just peripherally about movies. It's more about all these people who, of course, were affected by the movies. I don't know why I haven't done more. I don't really want to make a profession of making movies about the movies.

AC: Does it bother you to be primarily identified in the public eye now as a film director, when so much of your career has been devoted to acting and writing?

PB: There was generally misapprehension about me for many years because people thought of me as a critic who became a film director, and that's really off the mark. I was never really a film critic. If anything, I was a film historian or a kind of popularizer or enthusiast. But I really began in show business as an actor. That was my early training and my slant. And I think people's impression that I began in the business as a critic gave rise to an awful lot of stupid writing about me, because when you base something on a fallacy, what comes out of it can't really be accurate. So people would say, "He was a critic and so therefore he made this film," but that really isn't the case. I never thought of myself that way. My whole experience, starting with acting at the age of 15, comes from a totally different place. I can't say it upset me, but it bothered me -- this misapprehension of me.

AC: So if it wasn't the historical aspect, what was it about The Cat's Meow that attracted you to the project?

PB: I thought that the basic story of The Cat's Meow was very interesting -- tragic. It's a story in which nobody really gets what they want. The woman in the story is as much a victim as anybody, and she's caught between these two very strong men and has to try to find herself within that. It's kind of a metaphor of women's situation. Don't forget women had just gotten the vote. They had only voted once. It's strange now, but I think it is Marion's story more than anybody else's.

I was also interested in the story, which I had known from Orson Welles having told me the basic parameters of the story many years ago -- 30 years ago really, when we were working on a book. He told me that a version of the story had actually been in a sequence of Citizen Kane, but he had decided not to shoot it and had taken it out of the script. I asked him why and he said he didn't think his character of Charlie Kane would behave the way Hearst behaved under the circumstances. So when I got the script and read it, I thought, "Wow, I know that story," and I was immediately interested in it. It took a while before it ever got made, but that's how it started. It evolved. The script that we shot is not exactly the script that I received, but that's normal.

That's one of the ongoing confusions about Citizen Kane. It isn't really Hearst that Welles portrayed. And it certainly isn't Marion Davies. Yet people think that it's Marion Davies. On The Cat's Meow, we were definitely trying to do the real Hearst, the real Marion, the real Charlie. At least, do it as closely as we could.

AC: How involved were you in the casting? Some of it is quite inspired.

PB: Obviously, I'm very involved in the casting. I'm very involved in everything. The actors were all awfully good. We worked very carefully on the casting, and also got lucky. That's all I can say. Kirsten was particularly good, Ed Herrmann too. The idea for Eddie Izzard to play Chaplin was one of the most controversial bits of casting when I had the idea. And as it turns out, it probably still is the most controversial. But I think he's superb.

AC: How did you land your cool acting gig as the shrink to the shrink on The Sopranos?

PB: In the early Nineties, David Chase, who at that time was producing a series called Northern Exposure, called me and said they were doing a special episode that was kind of a tribute to Orson Welles. He invited me to come to Seattle where they were shooting and play myself in the episode. They would then write it for me if I would agree to do it -- play myself as a friend of Orson's, which was true. They made up a fictional reason for why I would be there and all that. I said sure, and they wrote it, and I went up to Seattle and shot it and was there for about four or five days. After I'd shot for a day or so, David called me up and said, "Have you ever acted before?" I said, "Yes, I started out as an actor." He said, "You're very good at it. You ought to keep it up." I said, "Thank you." He said, "You have a lot of presence." I said, "Thank you." Seven years later, he called me up and said, "I'm doing a series called The Sopranos." I said, "Yes, I know." He said, "There's a psychiatrist in it." I said, "Yeah, I know. I've seen it." "And she gets so troubled with her problems with Tony Soprano that she goes to a psychiatrist. And we'd like you to play that. Would you come down and talk about it?" I went down and talked about it. Everybody agreed I would be good. So I said, "Sure, I'll do it," and that's that. I'll be in the upcoming fourth season, which starts in September. I love doing it. n

The Cat's Meow opens the SXSW Film Festival on Friday, March 8, 6pm, at the Paramount Theatre (713 Congress). Director Peter Bogdanovich will introduce the film.