Brave New Web

Local hackers react to the passage of the USA-Patriot Act

By Michael Connor, Fri., Dec. 14, 2001

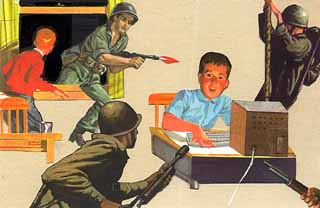

You're probably scared of hackers.

And who wouldn't be? They have the ability to topple corporations, send stock prices reeling, ruin your personal credit, and distribute false news stories, sending us all into the streets in a War of the Worlds-like panic.

But that's not the whole story. Hackers gave us the Apple computer. They've improved Internet security. They fought for civil liberties on the Internet. They gave Ferris Bueller his day off.

There are all kinds of people who classify themselves as hackers, ranging from mild-mannered, law-abiding programming geeks to credit card thieves with organized-crime connections. They're a fractious community -- usually male and in their late teens to early 20s, with a cavalier attitude toward Internet law. That community now finds itself at the center of a renewed debate over the nature of the Internet as a free system. In the post-WTC world, utopic hopes for a democracy of information have been supplanted by fears of the power of this tool to cause harm. As a result, trends toward regulating the Internet have accelerated, and advocates of freedom in cyberspace have been pushed to the margins. It's a new World Wide Web out there.

Public Enemies

Bob is not your average high schooler.

Recently, the 17-year-old Austinite hacked into a major Hollywood studio's computer system and stole a copy of a yet-to-be-released blockbuster movie. As a result, he is one of only a few people who saw the original cut, complete with the line "man chowder," a potentially classic catch phrase that ended up on the cutting room floor.

Bob -- whose name was changed for this article -- plays in a band, writes brilliant computer programs, and used to count himself a member of the "cyberpunks," the vandals of the computer world. When he talks about computers, his speech accelerates as the words struggle to keep up with his brain. "We used to break into the elementary school computers to try and change grades, and if we didn't like people we'd put fines on their library books. It would mainly be me and friends who didn't know anything about computers, they'd be looking over my shoulder and chanting 'Bob! Bob! Bob!'"

He has an illustrious reputation as a hacker, but Bob relates his conquests, like the "man chowder" one, with an air of detached amusement and a noticeable lack of bravado. So why did he do it? "Definitely for the challenge of it. It's a thrill -- it's like skydiving or something. You know, that falling feeling like when you're in a roller coaster or something, when you're in there covering your tracks, trying not to get caught."

Former Austin resident Lloyd Blankenship illustrated that feeling of exhilaration in 1986 in an unofficial hacker manifesto (known as Conscience of a Hacker) that's been circulating on the Internet for years. Blankenship describes the sensation of hacking as "rushing through the phone like heroin through an addict's veins, an electronic pulse is sent out, a refuge from the day-to-day incompetencies is sought ... a board is found. 'This is it ... this is where I belong.'"

Indeed, for the teenage hacker, it's all about the belonging. In order to be accepted into elitist cyberpunk subcultures, some young hackers commit risky and damaging crimes. Low-level, less skilled hackers (derided as "script kiddies") often vandalize Web sites or steal personal information to impress their friends and other hackers. But the criminal element is the exception, not the rule. Sergeant Robert Pulliam of the Austin Police Department says criminal hacker activity is rarely reported in Austin. "It's been a year and a half since we had a hacker case here in Austin. ... Either there are no hacker groups operating in Austin, or we don't know about them."

One group that has operated under the radar is the Austin 2600 Group, which meets monthly to connect and talk shop. The local chapter is part of an international movement loosely organized around 2600: The Hacker Quarterly, a magazine about the computer underground. The monthly meeting is billed as "a forum for all interested in technology to meet and talk about events in technology-land, learn, and teach." Or, as member Joseph Stine put it, "We're just harmless geeks who have a good time staying up all night and writing code."

The 2600 meeting, held in the food court at Dobie Mall, is very much like the geek table in the high school cafeteria. One of the hackers plays with some scrapped hard drives. At the other end of the table, some take a surreptitious digital picture of a security guard. They talk about wireless Ethernet nodes around town. They swap code. There's a moment of excitement when one of them causes a system crash and restart on his cell phone. At one point, a newcomer to the group says he's not sure if he really qualifies as a hacker. Tami Friedman, a veteran member, administers a quick hacker test: "If a program doesn't work the way you want it to, do you fix it? Do you stay up all night writing code? Do you read the manual before you start using new software?"

As in any clique, especially one considered "outcast," there's a real bond among the 2600 Group, and they can quote Conscience of a Hacker from memory: "We explore ... and you call us criminals. We seek after knowledge ... and you call us criminals. We exist without skin color, without nationality, without religious bias ... and you call us criminals."

In the current political climate, the "criminal" label is more apt than ever.

Taking Liberties

Since September 11, the U.S. government is facing a new public mandate: Prevent terrorism before it happens. With good reason, the American people expect officials to make the country less vulnerable to attack, and to make arrests before the crimes are committed. But in order to do so, government agencies have deemed fitting a return to J. Edgar Hoover-style intelligence gathering and surveillance on the basis of suspicion rather than evidence.

The first step was the passage of the USA-PATRIOT (Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism) Act on October 26. The purpose of the law is to make it easier for law enforcement to fight terrorism, and it contains many sensible provisions to that effect. But it also implements sweeping changes in the U.S. legal code that deserved serious debate. Faced with enormous pressure from the Bush administration, Republican Party leaders pushed the bill through Congress without sufficient scrutiny. Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., criticized the pending legislation during floor debate, saying "this bill, ironically, which has been given all of these high-flying acronyms -- it is the Patriot bill, it is the USA bill, it is the stand-up-and-sing-'The Star Spangled Banner' bill -- has been debated in the most undemocratic way possible, and it is not worthy of this institution."

Several of the more troubling provisions of the USA-PATRIOT Act deal with the Internet. Marc Connolly of the U.S. Secret Service states that the act also "authorizes us to create a national network of electronic crime task forces." The purpose of the new task forces will be to hunt down domestic electronic criminals rather than cyberterrorists, who fall under the jurisdiction of the Office of Homeland Security. The law institutes harsher and broader penalties for hacking into a protected computer -- even if no damage is done. This clause criminalizes less serious forms of computer cracking that have been overlooked in the past.

Tommy Wald, an Internet security expert with Austin-based Riata Technologies, questions the effectiveness of these clauses. "The whole idea of raising the penal code will eliminate a certain portion of hobby hacking and nuisance hacking, but it won't deter more destructive international cyberterrorism. It's going to have a minimal effect." Instead, it will have an effect on people like Bob, who would face federal prison for his Hollywood studio hack under the new law. "It's ridiculous, but not unexpected," he says.

Another controversial provision of the USA-PATRIOT Act allows increased use of Carnivore, a wiretapping software for the Internet. Carnivore is installed on an Internet Service Provider (ISP), such as AOL, in order to monitor the e-mail and Web-browsing habits of a suspect under surveillance. Civil libertarians have long contended that this tool could be easily used to conduct unlawful surveillance of ordinary citizens. Now, the USA-PATRIOT Act allows for the implementation of the Carnivore system without a warrant in some cases. "I can concede that there are times that the government has a legitimate need, even a mandate, to access communications on the Internet," says Austin-based attorney Scott McCullough, counsel for the Texas Internet Service Provider Association. "But I consider [the USA-PATRIOT Act] to be a huge overreaction. Terrorists who are organized enough to do what we saw on September 11 are going to use high-level encryption ... rendering Carnivore useless." Carnivore would be useful only against someone who had no reason to conceal the content of his or her e-mail. Again, the effect on combating terrorism will be minimal, at the potential cost of civil liberties.

Closing Up Shop The USA-PATRIOT Act isn't the only controversial measure the government has taken to increase security since the terrorist attacks. Several government Web sites have been shut down. Shortly after the attacks, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission closed their entire Web site, pending review (some of it is now back online). Christie Whitman's Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was quick to follow suit, deleting from their site information that dealt with the potential risks of industrial accidents and the like. "The presence of this information could provide information to terrorists," says Dave Barry, spokesman for the EPA in Dallas. Environmentalists have fought a number of legal battles to keep this information in the public eye since the mid-Eighties, touting it as an important way to keep corporations accountable for their environmental practices. Now, without even a court hearing, it is gone.

Critics charge that the government is guilty of political opportunism, using a time of crisis to push an old agenda of greater regulation and increased federal power. In more peaceful times, the American people would not stomach such infringements on their civil rights. Now, it seems, Americans will stomach pretty much anything. "I am convinced that the government is using [the terrorist attacks] as an excuse to accomplish the same goals that it has stated for years," says McCullough. "Many of the new provisions don't relate to what we perceive of as terrorism. They're incredibly broad about what terrorism is." These provisions relate to minor criminals and people whose First Amendment activities might be deemed a threat to national security -- such as hackers.

Bombs Away

Jim Choate is one such threat. The 42-year-old local software engineer at IBM is a principled, intelligent activist who believes that technology should have a more organic role in society. He believes in a democratic solution to our problems, in communication to promote consciousness, in the Constitution of the United States, and a whole host of other things that fall just short of teaching the world to sing. And, incidentally, he exercises his First Amendment rights by distributing bomb plans on the Web.

"How many people have read [bomb plans] on the Internet and realized that a 12-year-old was collecting bomb materials, and stopped them?" Choate says. "It seems the potential for intervention is greater than the possibility for prevention."

Choate sees his exercise of free speech as a thumb in the dike against the growing threat of a government monopoly of information. He's part of the cypherpunk movement, a sort of hacker subgroup and network of Internet freedom and privacy advocates. The cypherpunks take privacy very seriously. If you're interested in attending one of their meetings, just go to Central Market on the third Tuesday of every month and look for the group with the Applied Cryptography book on the table. It's red and about one-inch thick.

There's a reason for all the cloak-and-dagger stuff: Like most hackers, the cypherpunks are often running afoul of the law. In particular, they're infamous for figuratively tweaking the noses of people who lack a sense of slapstick, such as the FBI. The cypherpunks' idea of a good joke is releasing a classified federal document on their public listserv.

Like the cypherpunks, ®™ark (pronounced "art mark") is an underground group that uses hacker tactics to bring about social change. They're best known for the Barbie Liberation Organization prank of 1993, when they switched the voice boxes of talking Barbie and G.I. Joe dolls and then returned them to toy store shelves. More recently, they organized a virtual sit-in, or "denial-of-service" attack, against Etoys.com during the 1999 Christmas season. ®™Mark was protesting a court-ordered closure of German art collective Etoy.com, which predated Etoys.com by several years. To close down the Etoys Web site, a large number of people logged in over and over, slowing the server to a crawl. The sit-in crippled the company's sales during the all-important Christmas season.

The success of the Etoys sit-in starkly illustrated how effectively hacking may be used as a tool of the powerless against the powerful. The history of hackerdom is a history of chafing against authority. From the early days of computing, hackers were the anti-establishment. They were the spunky freedom fighters, and IBM was the oppressor. Over the years, though, the hackers' motivations have varied widely, this dynamic has remained fairly constant -- hacktivists have taken on everyone from Microsoft to MGM to Ma Bell. Now, in the current unstable world order, U.S. sites seem to be prime targets for hackers.

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks, both anti- and pro-U.S. hackers have mobilized, defacing Web sites and launching denial-of-service attacks. One of the first victims of this disorganized, unofficial cyber-war? A Web site about Afghan hounds, which was defaced on September 12. Still, an October report from the National Infrastructure Protection Center said the possibility of a serious cyber attack from abroad remains low, though "the threat is higher than before September 11."

Access Denied The domestic response to the September 11 tragedy has been to circle the wagons, so to speak. When it comes to the Internet, the potential dangers suddenly seem to outweigh the benefits. McCullough forecasts grim consequences of this current trend. "I think the so-called 'controllers of wealth and power' have decided that this plaything [the Internet] is a sharp instrument that children shouldn't be allowed to run and play with. The most positive aspect of it will be taken away. We will once again be relegated to the role of passive consumer instead of active citizen."

If this happens, it won't be without a fight. Choate was quick to answer when asked whether recent events would discourage him from posting bomb plans on the Internet. "Fuckin' a! Hell no! We've got a First Amendment up there. We've got a Fourth Amendment up there. If [law enforcement officials] don't like what I'm doing, doesn't that just validate it even more?"

In unsafe times, what amount of government regulation is necessary? What do we gain as a society from freedom and openness in the democracy of information? Since September 11, public officials have taken a hard line on the regulation of the Internet. What will be lost?

True, if there was ever a time for rigorous national security, this is it. On the other hand, if there were ever a time for a free exchange of ideas, this is it. ![]()