Playing on the Past

By Chris Baker, Fri., June 11, 1999

Gorf. QBert. Zaxxon. Kaboom. Yar's Revenge. Hunt the Wumpus. Dig Dug. For anyone who's ever played them, just hearing the titles of these vintage masterpieces can trigger an overpowering flood of sense memories -- the look of the chunky two-dimensional graphics, the hypnotic repetition of boinks and bleeps, the dull ache in your button thumb --a remembrance of video games past.

For those who haven't played these classic games, it may seem ridiculous that anyone was ever enthralled by them, and utterly appalling (or hilarious) that some people are still slavishly devoted to them. But consider this: "'Tis a Gift to Be Simple." That old Quaker hymn served as the theme music for Coleco's 1982 game Smurf: Rescue in Gargamel's Castle. The phrase also serves to encapsulate the appeal of retrogames: simple design, simple packaging, and simple gameplay with straightforward objectives. Curt Vendel of the Atari Historical Society says, "To coin a phrase from Nolan Bushnell [the founder of Atari], 'Make the games easy to learn and hard to master,' and that's what they did."

Not only were these retrogames just simpler to understand, that simplicity made it easier for a players to lose themselves in the onscreen figures. In her book Joystick Nation, J.C. Herz writes, "It turns out that players actually identify more with the blocky, primitive, symbolic characters than with these 3-D polygon action figures. ... Characters in Mortal Kombat have fingers and stubble. You watch them. Pac-Man has one black dot for an eye, and you become him."

Not only were these retrogames just simpler to understand, that simplicity made it easier for a players to lose themselves in the onscreen figures. In her book Joystick Nation, J.C. Herz writes, "It turns out that players actually identify more with the blocky, primitive, symbolic characters than with these 3-D polygon action figures. ... Characters in Mortal Kombat have fingers and stubble. You watch them. Pac-Man has one black dot for an eye, and you become him."

You won't find many techno-Luddites willing to argue that classic games are better than the latest ones. Modern games are kinetic and viscerally exciting. They offer sleekly cinematic graphics, exquisite control, and the freedom to conjure up entire worlds.

But the old games refuse to die.

Some arcades in town still hang onto tried-and-true standbys like Elevator Action, Galaga, or Ms. Pac-Man, and often they're just as popular as their newer neighbors. You can find classic games and game systems at flea markets, thrift stores, and the City-Wide Garage Sale. In fact, it's still possible to order replacement parts from Radio Shack, and you can still purchase used cartridges from Gamefellas in Northcross, Lakeline, or Barton Creek Mall. And if anyone pulls one of these babies out at a party, rest assured that it'll be the center of attention all night.

However, the real action in the retrogamer community is happening online. Any cursory Net search on classic games will turn up endless lists of newsgroups, fan sites, swap lists, new versions of old games, and instructions on how to cheat at them, impenetrable explications of archaic programming languages, and, of course, lots of people trying to sell you stuff.

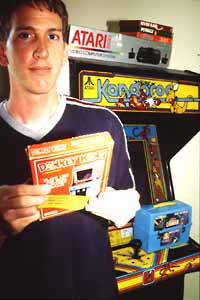

"Classic games have always been, and still are, a niche hobby, but one that's definitely growing," explains Alexendar Bilstein, an Austinite who created the Atari 2600 Nexus Web site. "Ebay, the Internet auction site, has given birth to a large number of classic gamers over the last year -- people stumble across a listing for an Atari 2600 that they haven't thought about in 15 years and get sucked into the hobby."

The Atari 2600 was the titan of the home video game industry from the late Seventies to the mid-Eighties, and it still reigns supreme in the hearts of countless retrogamers. A recent Ebay search produced no less than 867 Atari 2600s available for bidding. "The 2600 is definitely the king," says Bilstein. "It's basically the original blueprint for video game consoles that is still followed today."

The Atari 2600 was the titan of the home video game industry from the late Seventies to the mid-Eighties, and it still reigns supreme in the hearts of countless retrogamers. A recent Ebay search produced no less than 867 Atari 2600s available for bidding. "The 2600 is definitely the king," says Bilstein. "It's basically the original blueprint for video game consoles that is still followed today."

Austinite Brad Fregger was director of training at Atari and a game producer at Activision during the golden age of video games. "Many of us knew we were making history," says Fregger. "Nobody has any idea what it was like at Atari from 1979 to 1983. This was the wave of all waves, a ride beyond compare." A wave so huge, its ripples are still being felt, especially in a town as nostalgic and sentimental as Austin.

"In my opinion, there are certainly a large number of [classic games] collectors in Austin," remarks Bilstein. But while the interest clearly exists, Bilstein is still having difficulty creating a community. The classic games conventions he's held for the past couple of years have been "pretty small and informal. They were just held at a friend's place."

"I didn't even know they had classic gaming expos," says Fregger. "I would attend one if it were here in Austin. It would be great to see and play some of these old games again, especially Pitfall II on the Atari 800 [which Fregger produced at Activision]."

So why this continuing interest in the old games? Is it just another symptom of the Gen X fetish for all things Seventies? Well, a kid who was 10 when Atari hit its peak in 1982 would be 27 now -- time to be a grown-up, get a real job, maybe even (gulp) settle down. Maybe like all other retrotrends -- clothing, music, film -- the rise in the interest of retrogames is just another example of the need for the familiar comfort of childhood. Or maybe when you get down to it, the games were just better then.

Curt Vendel, who maintains the Atari Historical Society's online Virtual Museum, notes that, "People want to go back to a simpler time where you walk up, read two lines of instructions, and knew the game. People want clean, simple challenges, and are tired of the 45-move joystick/button combinations it takes to do a roundhouse kick."

Modern games require diligence and commitment. In order to play the home game G-Police, a player must watch a 45-minute film that explains the back story of the game, then spend weeks learning how to maneuver the ship before ever actually playing the game. Retrogames, on the other hand, offer the more direct hedonistic pleasures of the era that spawned them. Treat a classic like Missile Command to a few quarters' worth of introduction, and it'll rock with you all night.

Fregger, who helped create some of these classics, says that the early programmers had no choice but to make games using their creativity. "The big difference was that the early games had to depend on gameplay because the graphics capability wasn't very good. Many modern games are either multimedia-intensive, with weak gameplay, or boring copies of something that was extremely popular. ... Many of the modern game designers have forgotten the essential characteristics of a game that grabs you and doesn't let go."

Fregger, who helped create some of these classics, says that the early programmers had no choice but to make games using their creativity. "The big difference was that the early games had to depend on gameplay because the graphics capability wasn't very good. Many modern games are either multimedia-intensive, with weak gameplay, or boring copies of something that was extremely popular. ... Many of the modern game designers have forgotten the essential characteristics of a game that grabs you and doesn't let go."

Bilstein says that for many, the pursuit of retrogames means a lot more than just rewinding back to their childhoods. "There's a more serious appreciation some people have for the history, the innovation, and the amazing games that some programmers were able to create with only 2K of memory."

Appreciation? Serious?! The words have the connotations of junior high music classes -- not of something entertaining, but of something that's (shudder) good for you. And while it's hard to find retrogamers who take themselves or their hobby too seriously, you don't have to look very hard to see a strain of sober historicism mixed in with the fun and games.

"It's archaeology, pure and simple," says James Hague, author of Halcyon Days, a collection of interviews with classic game programmers. "In 1978, there were only a handful of computer games. By 1984 we'd already churned through a thousand or more games, including dozens of true landmarks: Star Raiders, Eastern Front, Choplifter, Flight Simulator, M.U.L.E. The history accumulated during those six years is very thick."

What makes this task of archeology difficult is the fact that the games' creators often went completely uncredited for their work. Hague, who himself wrote the early game Bonk ("You ran around in an open maze and were chased by critters that bonked backward for a few seconds after they hit a wall"), also has a Web site called the Giant List, which singles out all the forgotten makers of the golden age games.

This lack of respect became a real problem in the industry. Fregger and many of Atari's best programmers left the company over the issue of receiving proper credit. "This was one of Atari's biggest mistakes. The funny thing was that they were owned by Warners, who was supposed to know the value of star power. It just goes to show you how stupid some senior executives can be."

Determined to learn from the mistakes of Atari, these breakaways formed their own company. Fregger explains, "Activision gets the credit for bringing the names of the first video game star programmers to the public, with David Crane [Freeway, Pitfall, Decathalon] as the first star. The programmers were in charge. They started the company and they decided what they would make." This primacy of the programmer helped Activision to make many of the finest games of the decade.

Hague asserts that part of the enduring appeal of the early games is that they were frequently made by these single individuals, "which makes them closer to other traditional forms of artistic expression." Like the greatest film directors of the cinema, they are auteurs, and with Hague's site, perhaps they will no longer be forgotten.

"A significant number of people who worked on early games obviously followed their own visions. Chris Crawford had a strong interest in linguistics, and his Gossip was a game about interpersonal relationships. Jordan Mechner cast a martial arts game [Karateka] as a drama, with camera cuts and a simple, advancing plot. Bill Williams, the Stanley Kubrick of game design, developed a surreal game about growing an army of trees from seeds and using them to infiltrate vaults containing spider eggs [Necromancer]. The key is that Chris, Jordan, and Bill weren't trying to please a paranoid marketing department or anyone in general. They just wrote the best games they thought they could."

Fregger disagrees about the role of the individual in the early days of video games ("We had teams making games very early on"), but he is in total agreement about the evils of the marketing department. "In the early days, we didn't have a clue as to what the public would like, so we had carte blanche to make anything we wanted. The programmers and artists I worked with took advantage of this situation and tried everything they could think of. As the industry matured, games got more expensive, and marketing got a better handle on what the public wanted. It's too bad, and it does affect the variety and originality of product ... but, it is a fact of life."

Fregger disagrees about the role of the individual in the early days of video games ("We had teams making games very early on"), but he is in total agreement about the evils of the marketing department. "In the early days, we didn't have a clue as to what the public would like, so we had carte blanche to make anything we wanted. The programmers and artists I worked with took advantage of this situation and tried everything they could think of. As the industry matured, games got more expensive, and marketing got a better handle on what the public wanted. It's too bad, and it does affect the variety and originality of product ... but, it is a fact of life."

So, like all things, the golden age faded and in its place came market surveys and demographics and business suits and video games that just weren't as inspired as their predecessors. But is there anything else we can learn from the early history of video games?

Hague explains, "The history of technology is much more varied and unpredictable than is commonly assumed. Looking to the past keeps us from thinking we know everything about the future. The other lesson is that inspired individuals are always more important than technology." But while the individual may be the most important aspect aesthetically and historically, the only thing that's important from a business

standpoint is the bottom line. For every bold new concept and thrilling breakthrough, you'll find a dozen retreats to the safety of the familiar. Lots of home games are simply versions of popular arcade games. Lots of arcade games are just last year's game with a Roman numeral after its title. Nintendo has spun off almost 30 Mario-related games from that holiest of holy relics, Donkey Kong.

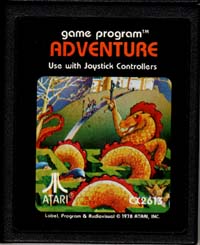

Recently released updates of Frogger, Pac-Man, Space Invaders, and Pitfall bear out this trend, but with a telling difference. All of these new versions are light-years beyond their ancestors design-wise, but interestingly, they all contain fully playable versions of their classic lo-tech incarnations imbedded within them. These scrupulously hidden "Easter eggs" became some of these games' most talked-about features and proved to be an enormous selling point.

Activision went them all one better; they re-released their entire catalogue of classics (River Raid, H.E.R.O., Sky Jinx, Freeway, Pitfall, et al.) on one disc for the Sony Playstation. All the games were in their original format, exactly as they had appeared almost 20 years ago on the Atari 2600.

Obviously, the industry is responding to the widespread popularity of emulators, which can take the lion's share of the credit for the growing interest in retrogames. An emulator is a program that lets you play old video games on your home computer. Almost any of the old video games. For anyone with Web access, the emulators are one mouseclick away. One cost-free mouseclick away.

But isn't that essentially a black market? Or at least a gray market? "It's gray all the way," remarks Hague. "The industry is scared, but slapping lawsuits on one's own fans doesn't make for a great public image. The precedent that's being set is 'old copyrights can be overturned by popular demand.'"

But isn't that essentially a black market? Or at least a gray market? "It's gray all the way," remarks Hague. "The industry is scared, but slapping lawsuits on one's own fans doesn't make for a great public image. The precedent that's being set is 'old copyrights can be overturned by popular demand.'"

Bilstein adds: "I have heard a number of copyright experts say that this is completely legal, and some software representatives say that it is not. But the initial reaction of the gaming industry, which was to try to get rid of emulation entirely, seems to have been replaced with a more tolerant attitude. The future is uncertain, however."

In the meantime, there's much to be said for the emulators. "What great fun it is to fire up a game I remember seeing once at a 7-Eleven in 1982 but didn't have a chance to play," says Hague.

"I remember believing that nobody would ever be able to play these games because the systems they played on would no longer be available," says Fregger. "I think it's wonderful that people who care have found ways that they can be played and remembered forever."

Fregger would like to see one of his overlooked gems get a second shot at fame online. "Pharoah's Revenge was a fantastic product. I own it and would gladly release it to emulators."

Emulators allow us to see and experience games that we would never otherwise have encountered, but there are other drawbacks besides the legal implications. Like a K-Tel greatest hits compilation or an evening's worth of programming on Nick at Nite, emulators can destroy the historical context of what they purport to be preserving. This is particularly troublesome since there's now a new generation of game fans with no firsthand knowledge of their classic game heritage.

"I'm starting to see some strange rewritings of game history," says Hague. "Some people think that Donkey Kong is a clone of the Apple II game Cannonball Blitz, for example, when in reality it was the other way around." Hague also notes that most games were designed with a specific physical appliance in mind, one that was often quite different from your typical home computer. "Tron is all but unplayable without the joystick and rotary control of the original coin-op, to say nothing of the black light on the cabinet."

Not surprisingly, Fregger owes this to the superiority of the original product. "The big problem is that they've never invented a joystick that works as good as the original Atari one. ... The old machines responded quicker than the computers do."

Another retrogamer, Randy Crihfield, freely concedes the wondrous possibilities of emulators. "You can pause when you want to go to the bathroom," he points out. "That used to be quite the killer when you'd hand the joystick to your little brother 'just for a second' and then come back and find your guy dead. (And he's playing some other game to boot!)"

But in the end, Crihfield knows that there's just no substitute for the genuine object. "Anyone can find [a game] on the Net, but try to plug that into your 2600; it just don't happen without me making a cart for it."

Cart? That's retrogamer slang for Atari cartridges, which Crihfield makes and sells through his Web site Hozervideo. He recycles the old plastic casings and inserts the freshly copied programming for whatever game you desire. "The appeal for me is I had some of these games when I was a kid but couldn't afford them all." Now he has virtually every Atari game ever made.

|

|

Now Crihfield sells them all, and all for just a little more than it costs him to manufacture them. And while Crihfield himself is still on the lookout for even more lost games, like Mr. Bill, Tempest, Ewok Adventure, and Pink Panther, he performs an invaluable public service by ensuring that the classic games he already has are readily available. He also offers several "carts" that challenge our very notion of what "retrogames" can be. Crihfield sells new retrogames, games created from scratch by amateurs using the old programming languages, made solely for use on the old game systems.

"There is quite an active community of programmers for a number of defunct systems," notes Bilstein. "New games have been created in the last few years for the 2600, Colecovision, Vectrex, Odyssey2, Jaguar, and Lynx, to name a few. These are all 'dead' systems, yet the fan base has kept them alive."

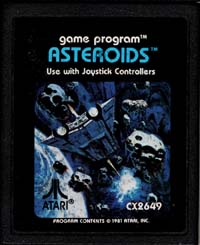

Retrogame fans, like all fan bases, combine a childlike sense of enthusiasm with the grown-up's desire to understand, articulate, and pass on that enthusiasm. Ultimately, it's the intensity of the fans' enthusiasm that saves retrogames from simply becoming a piece of history. It's this enthusiasm that the 35-year-old Randy Crihfield ("last of the baby boomers," he says) shares with his 11-year-old son when they play Atari.

"We have more modern systems, but those games are either solo-type games or, if they are two-player, fighting games. It's fun to compete, but why does it have to be head bashing? We like games that go head to head, like Oink!, and we like games that take turns, like Asteroids.

"My son and I sit down and play them together and have a blast. No, they are not the best graphics I have ever seen in a game, but they are fun, and we do it together. I hope my son realizes that there's always a prettier video game system, with faster gameplay, better graphics, etc. ... But it's too easy to want the biggest house, the fanciest car, the best video game system. Why not a modest house, a reliable car, and a simple game system that's got lots of father/son games? What's the old phrase, they just don't make 'em like they used to? Well, I still do."

For more info on the August convention, e-mail Bilstein: bilstein@mail.utexas.edu.